Essay

The Rules of the Game: Francis Alÿs at the MUAC

by Stefanía Acevedo

Reading time

7 min

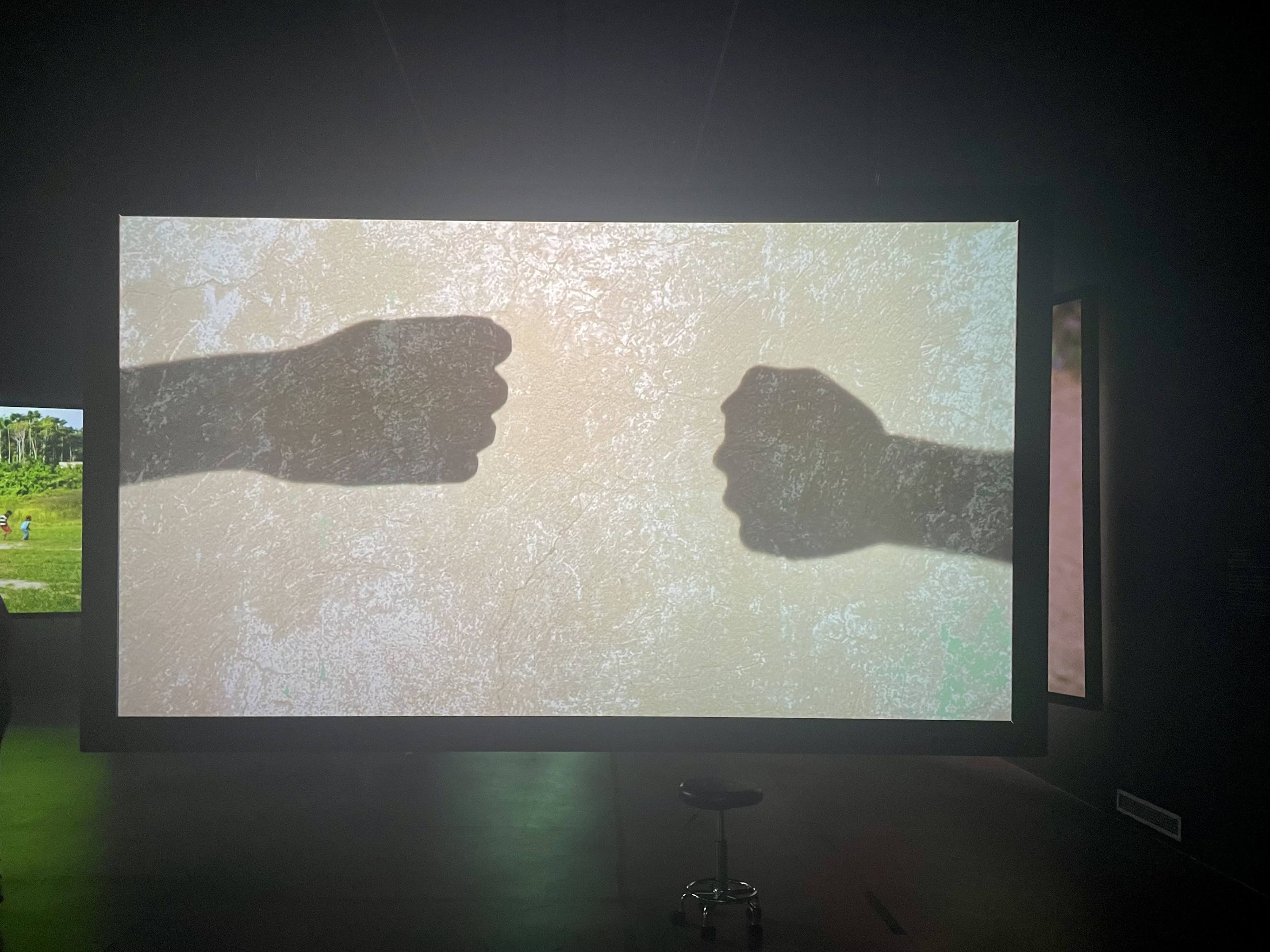

Francis Alÿs presents Juegos de niñxs (Children's Games), a series of 27 videos filmed between 1999 and 2022, along with 2 paintings, curated by Cuauhtémoc Medina and Virginia Roy. The exhibition is open until September 17th. If you visit on the weekend, you will likely find many children in the room, it's like being in eternal recess. Sometimes the shouts of the children in the videos blend with those of the children playing on the wheely chairs that allow you to move from one screen to another. Farewell to contemplative silence.

What are the necessary conditions that make up a game?

In all games, there's a tension that builds up and repeats itself. It's accompanied by uncertainty; you never know what the outcome will be. However, laughter always intervenes, bringing a lightness close to joy. Just like in game #26: Kisolo [Mancala] (Democratic Republic of Congo, 2021), where spectators remain silent as they watch the players, deeply focused, gathering pebbles with their hands; when someone wins, everyone celebrates, shouts, and laughs. Without this tension, only boredom would remain.

First rule: A game must maintain tension.

This tension involves taking the game seriously but also not at the same time. This isn't a hypocritical pretense. Unlike adult dynamics, a game involves embracing both intensities simultaneously because it can always start again, allowing movement between seriousness and non-seriousness. The game is iterable and can be reproduced in any context because they are citations of inherited games; every time something is repeated, it changes as it's performed by different people in different territories. If something can't be repeated, then it can't enter the dynamic of the game.

The tension between seriousness and non-seriousness isn't a lack of commitment. It's the radical acceptance that a game can end today but restart tomorrow with the same or different people. A game is a finite organization.

Second rule: A game must be repeatable.

A game can also be interrupted, be it due to rain, because someone or several people have to leave, or due to gunfire. A game can't be fully controlled. When playing with snails, as in #31: Slakken [Snails] (Belgium, 2021), you're subject to their slow movement; the children can't make them move. It's a matter of luck.

It can also be interrupted because someone no longer wants to play. One can decide when to end. Sometimes the tension in games involves a bit of pain that lasts as long as one wants it to. If your hands hurt a lot, you can ask for time, as in game #21: Hand Stack [Slap] (Iraq, 2018). There are key phrases: "Pidos!"

If a dynamic can't be interrupted, then it's not a game. That's why #5: Revolver (Mexico, 2009) is fundamentally different from a scene with firearms.

Third rule: A game must be interruptible at any moment.

You have to know how to move, as in #34 Appelsindans [Dance of the Oranges] (Denmark, 2022), where the children dance and constantly make their own calculations to prevent the orange from falling. Improvising, but also reading the movements of others, as in #19: Haram Football (Iraq, 2017), where an imaginary ball is played due to the prohibition of real football (haram). The players know where the invisible ball is going based on body movements.

Fourth rule: In the game, improvisation is necessary.

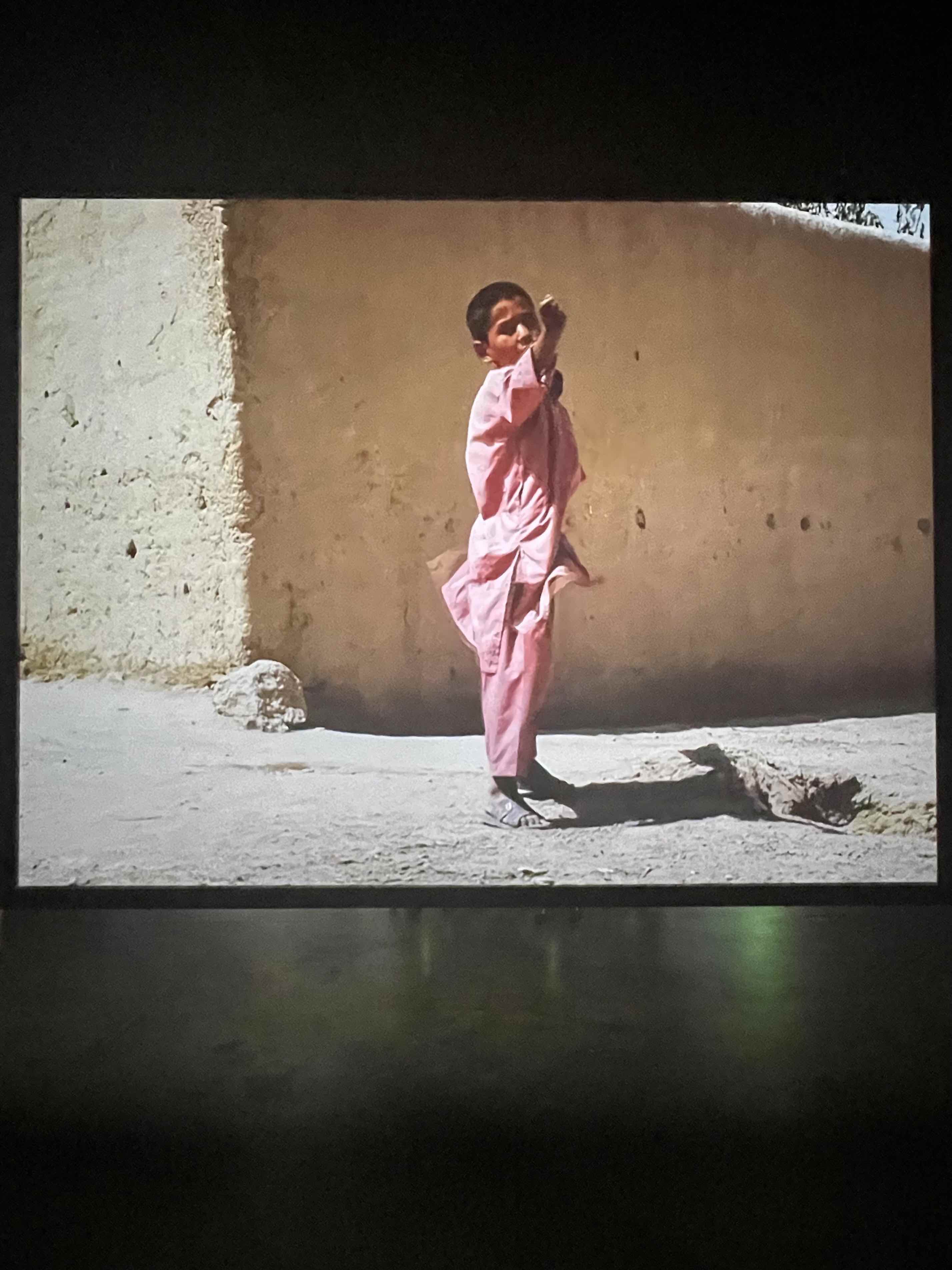

There's almost always a goal that accompanies the game, appearing solitary, like in #10: Papalote (Afghanistan, 2011), where there are non-human companions like the wind with which the child plays until finding the right rhythm with their hands. Or like in #29: La roue [The Wheel] (Democratic Republic of Congo, 2021), where the tire and the hill in the cobalt mine are playmates.

Whether alone or accompanied, the game is something that you learn to prepare. In #26: Kisolo [Mancala] (Democratic Republic of Congo, 2021), the children carefully prepare their stage, using knives to dig holes in the hardness of the ground. They stop to count them, perfecting the drilling technique with a spoon to make them round, and finally, they place the stones.

Caring for the stage also implies caring for others, and because games must be taken seriously, it's understood that the goal is never to hurt. Hence the calculations in the game #21: Hand Stack [Slap] (Iraq, 2018). A game can mimic the context, bringing violence and death into a dynamic of repetition and interruption: killing without killing [#15: Mirror (Mexico, 2013)], infecting without infecting [#25: Contagion (Mexico, 2021)]. Each game requires a technique that opens up possibilities for something to happen. The game is the technique closest to freedom.

You can play in the most hostile spaces and contexts, as in game #16: Hopscotch [Airplane] (Sharya Refugee Camp, Iraq, 2016), where children gather because they know it's still possible. In certain territories, playing involves dangers: from flying a kite to rolling inside a tire. Therefore, care and play go hand in hand.

Fifth rule: In the game, conditions must be taken care of for there to be a game.

Almost always, someone has to teach you the game's dynamics. Sometimes you learn just by watching, other times you invent the game yourself. In any case, you need to know the rules and agree with them, even if they involve collectively imagining the movement of a ball, removing the legs from grasshoppers [#9: Grasshoppers (Venezuela, 2011)], or summoning mosquitoes and killing them [#30: Imbu (Democratic Republic of Congo, 2021)]. But the above doesn't mean the rules can't be changed, not only because they are borrowed references, but also because one can choose their inheritance and create other games.

Sixth rule: The rules of a game must always be changeable.

In some games, there are winners and losers, but that doesn't mean a game is a competition. It's important to differentiate between playing and competing; only in the former is there lightness. In the game, one must learn to lose. What is at play when one loses? Undoubtedly, a momentary disappointment. No matter how much frustration losing may cause, it can always be repeated, and what was lost can be regained. Perhaps the game is the first place where we learn to lose, but also where we can play another song, as in the game #12: Musical Chairs (Mexico, 2012). If winners, losers, and spectators don't laugh at the end, if heaviness prevails, then there wasn't a game, but rather a competition.

Seventh rule: One must learn to lose.

What is expected when audiovisual records are made in territories that were once colonies, where violence is experienced and lived daily so that other countries can play peacefully and without disturbances? I'm suspicious of the fidelity that these images seek, which, in the worst case, have the effect of exoticizing and prolonging, a gesture characteristic of anthropology. Ultimately, who has the passports to be able to leave these games and then enter other dynamics of speculation? Sometimes it is apparent that the children know they're being filmed; they look at the camera or hold back because they know they are being watched. One should ask what being filmed meant for them during the reproduction of their games, in order to be exhibited later. The risk of Children's Games: showing that even in the worst conditions, people still laugh and can have fun.

Where is the authorship in these games? What does it mean to extract these images and bring them to diverse audiences? Perhaps Francis Alÿs is aware of this, and that's why at the entrance of the exhibition we are greeted with a footnote in his text, indicating the type of licenses that frame these pieces. All of them have open licenses, Creative Commons BY-NC-ND, implying that they have no commercial value, but must be attributed to their author. In fact, this is the most restrictive of the six licenses offered because it only allows downloading and sharing the works without any modification. It seems that the artist wanted to change the rules of the game... but not too much.

Translated to English by Sebastián Antón-Ojeda

Published on August 24 2023