Review

Rebellion consists in looking at a rose until the eyes turn to dust | On Pájaro Piedra

by María Cristina Torres Valle Pons

At Kino

Reading time

5 min

A non-white cube with a fourth wall that is a movie screen and a prologue displaced somewhere else. The duality between nature and artificiality unfolds in order to challenge their names and the certainty of their opposition from the present ecological collapse, from the speciesist regime, and from extractivism.

From a historical point of view, ars (to make, to create), the common root of such concepts as “art” and “artificial,” has been opposed to natura (what is born). How and why can one make art about what language has cast outside its limits? Is it possible to make art from nature and not only about nature?

The project Pájaro piedra (“Stone Bird”), made up of an exhibition in Kino, two screenings at Cine Tonalá, and an exhibition at Patricia Conde Galería, explores the intersection between ars and natura from the point of view of such concepts as colonialism and the anthropocene in the work of seven artists, articulated by the curator Andrea Celda in collaboration with Elisa Celda.

In 2018 the Dutch photographer Anne Beentjes visited El Huizache in San Luis Potosí, a small rural community located just three kilometers from a toxic landfill that has poisoned the area for three decades: a wounded land with a bright green leprosy. The community is mistrustful when placed under the gaze of a white European body and her photographic camera. Una extraña invasión (“A Strange Invasion”) is the result of this approach between the expectations managed by a foreign imagination and an ominous encounter in a soil drenched with death; the series shows images of a land desecrated by industry, and the images’ negatives are eaten away by the same chemicals that leave their indelible mark on the landscape.

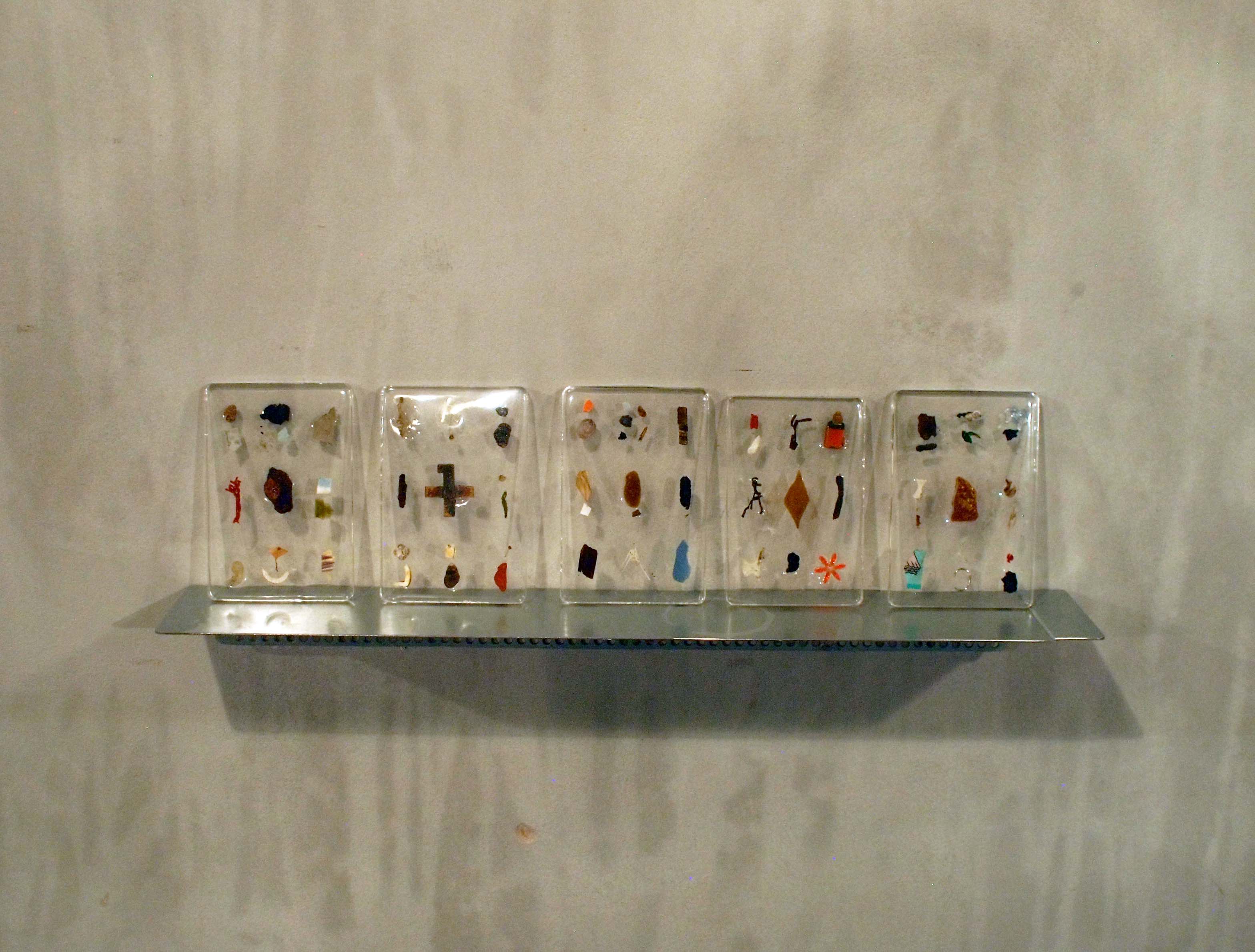

Two photographs and a video in black and gray show a person walking, waiting, and climbing the reliefs of some ancient piedra espuma (“foam stone”) on whose bed a woman managed to depict the Earth goddess years ago; A Chthonic Becoming (Mendieta’s Venus) by Ernesto Solana is the encounter between an untamed cave and bare skin (one half-tanned, the other almost untouched by the Sun). Then, being swallowed by the Earth right at the point where lies one of Ana Mendieta’s feminine invocations, and undressing in order to follow her map toward the subterranean, toward the underworld. In an inverse vector, the works Totemic Figure (Offering II) and Taxon Resin V - X (Antropocene Studies) reconfigure and encapsulate small fragments of any kind of object belonging to our time: flower-shaped plastic, metallic wire, printed paper, snail shell, etc.

In his film Fitzcarraldo (1982), the German director Werner Herzog tells the story of a businessman who dreams of exploiting the rubber of the Amazons and of founding an opera house in order to flood the jungle atmosphere with “great art.” Thirty-six years later, Adrián Balseca attends to the violence of this colonial imagination, subverting the operation with Grabador fantasma (“Phantom Recorder”), a solar-powered boat that records the sounds of the riverbed as it glides silently. A listening device that establishes a circuit opposed to its referent with a sensitive proposition in countercurrent. Perhaps we need to keep quiet and listen further. In grayscale, the screening of Skin of Labour articulates the film’s visual text about rubber extraction in the Ecuadorian Amazon with live sound by Space Cadet, once again insisting on the vitality of sound and its spatial presence.

Both the essay film Verás animales sobre la lluvia (“You Will See Animals in the Rain”), by Aldredo Ruiz Arias, and the feature film Perro lobo (Lycisca) (“Wolf dog (Lycisca)”), by Gerard Ortín, alternate between different perspectives on “the animal.” From a visual experiment marked by the discontinuity of scenarios in the first, to Ortín’s ethnographic and poetic exploration of the relationship between canids and humans in the valley of Karrantza in Spain, both films delineate a world in which any form of life, and any site on the planet, is subject to domestication and exploitation.

The project’s final counterpoint occurs at a certain distance, at Patricia Conde Galería. Cemetery (Archive Works) displays the sketches, notes, and germinating ideas of Cemetery, a feature film by Carlos Casas focused on the journey of an elephant together with its mahout, the last guardian of an elephant graveyard, at the end of the world.

Altogether, nature as perceived by Pájaro piedra looms from a deathbed, from an embalmed corpse, from a swan song, and from a forensic judgment. Voices of mourning and verses of love for a life that seems to wear itself out every night that dawns. Art with more or less permeable membranes in order to incorporate iconic and corrosive particles from the environment while floating in nature with an urge to swim in countercurrent, back home. Let us hope that we still have time to restore what we have stripped away.

“a look from the sewer

can be a vision of the world

rebellion consists in looking at a rose

until the eyes turn to dust”

Translation from “23.” Alejandra Pizarnik, Árbol de Diana. Mexico: Debolsillo, 2018

The exhibition can only be visited with a previously confirmed appointment, writting to kinotonala@gmail.com.

Published on March 18 2020