Review

About Mastica y Traga by Madeline Jiménez

by Stefanía Acevedo

At Alterna

Reading time

5 min

Mastica y traga (“Chew and Swallow”) is the first individual exhibition in Mexico of work by Madeline Jiménez Santil (Dominican Republic, 1986). The show, taking place in the gallery Alterna, began on September 5 under the auspices of Gallery Weekend. It was curated by Roselin R. Espinosa. The exhibition’s eleven pieces are framed by questions raised by the body. In her works the artist has produced a series of variations on these questions, treating them in their corporeal and material character. At the same time, what Jiménez has produced in her works are traced-out registrations of her own singularities, articulated under influences such as Lygia Clark, as well as dembow and trap: music genres that have allowed her to make a claim for feminine empowerment within the context of the Dominican Republic’s popular culture.

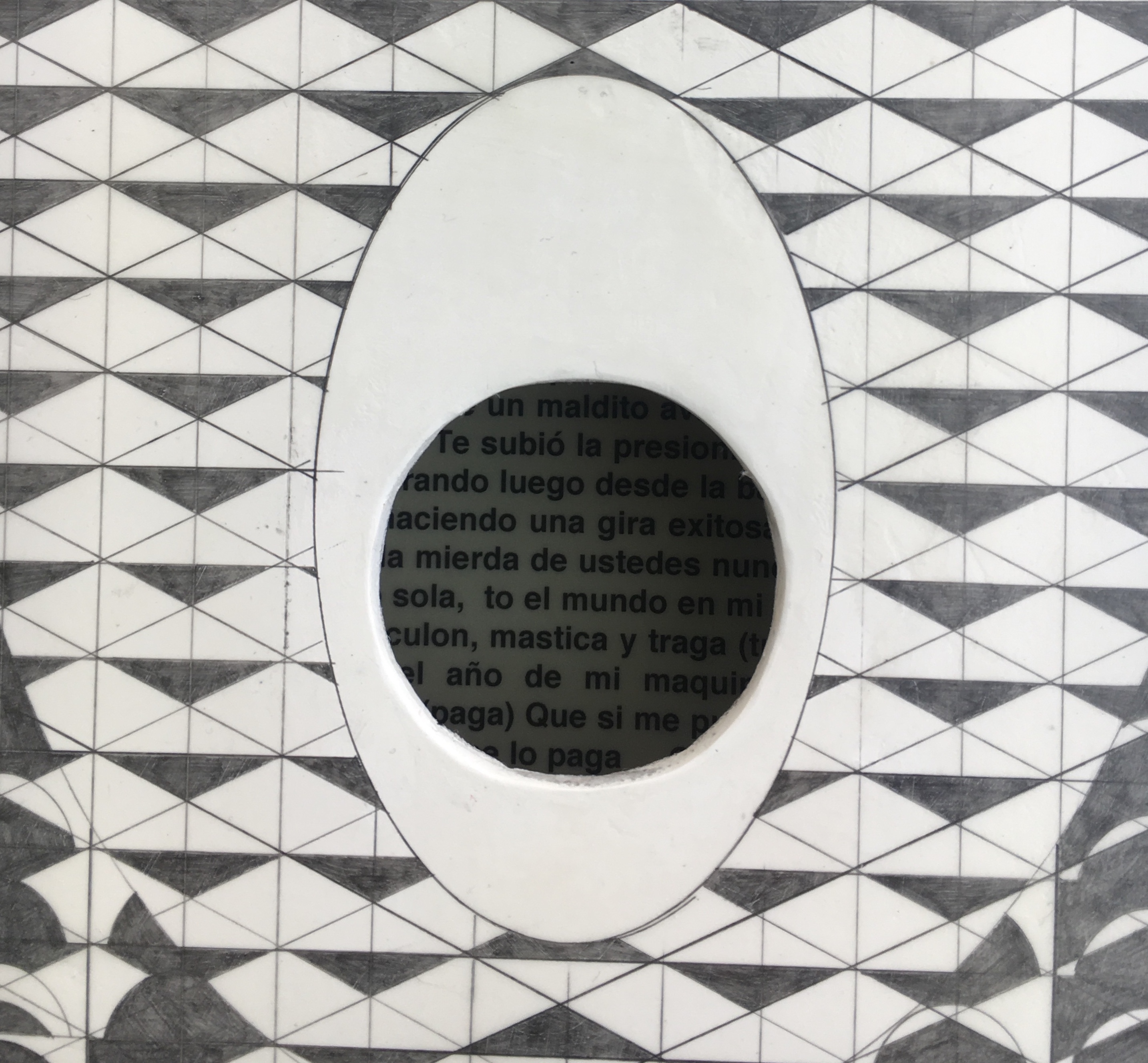

Before anything, the body that Madeline imagines in her pictures is composed of geometric graphite strokes that seem to generate their own rhythms. These “geometric codes,” as the curator calls them, refer to school exercises, allowing us to appreciate the technique by which Jiménez produces lines of different thicknesses that—despite their reiterations—do not form a premeditated order, but rather flow and haphazardly interrupt each other, beginning with black-and-white primary forms, but also immediately afterward appearing out of luxury brand logos. In this corpus, the measurements of such pieces as Autorretrato (“Self-Portrait”) and Glory Hole refer to the width of the artist’s shoulders, and each of the divisions that form on their surfaces correspond to the measurements of some other part of her body.

Apart from that, all the decisions regarding the arrangements of the pieces in the gallery constitute a proposal for treating questions about the body from the point of view of its very displacement. The curator and the artist have thought of Mastica y traga as a laboratory in which the works are distributed in order to evoke the dismemberment of organs, and in which they must be viewed from specific positions.

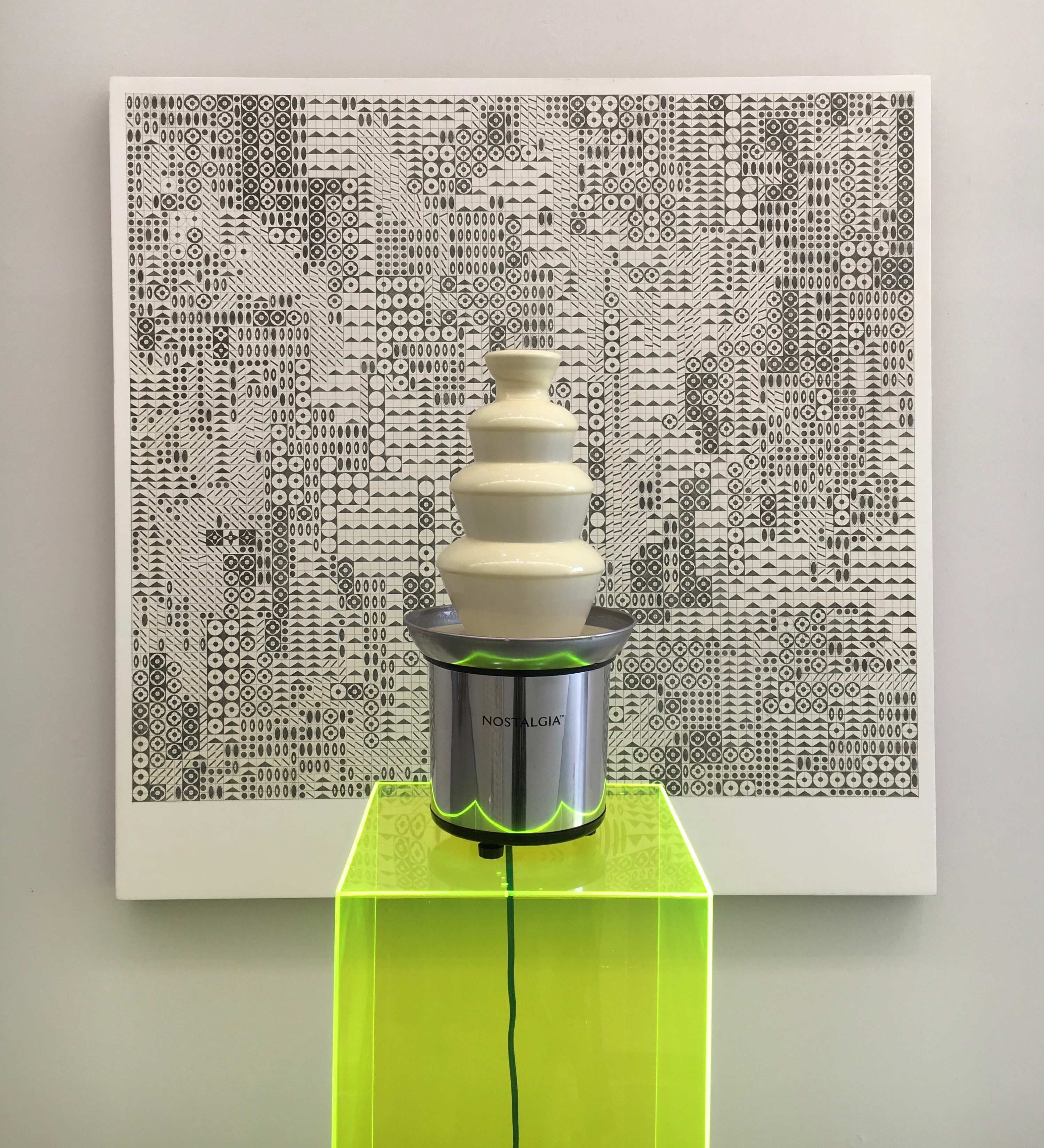

Pictures such as La mami swagger and Sistema disfuncional de escape (“Dysfunctional exhaust system”) are placed on the ground; while Autorretrato is placed on one of the walls, high above eye level; others seem to be in a kind of dialogue with their juxtapositions, such as La Fuente (“The fountain”/“The source”), located just in front of Limited Luis Vutton | Louis Vuitton Jungle, preventing us from seeing the whole of the piece or the patterns traced out on its surface.

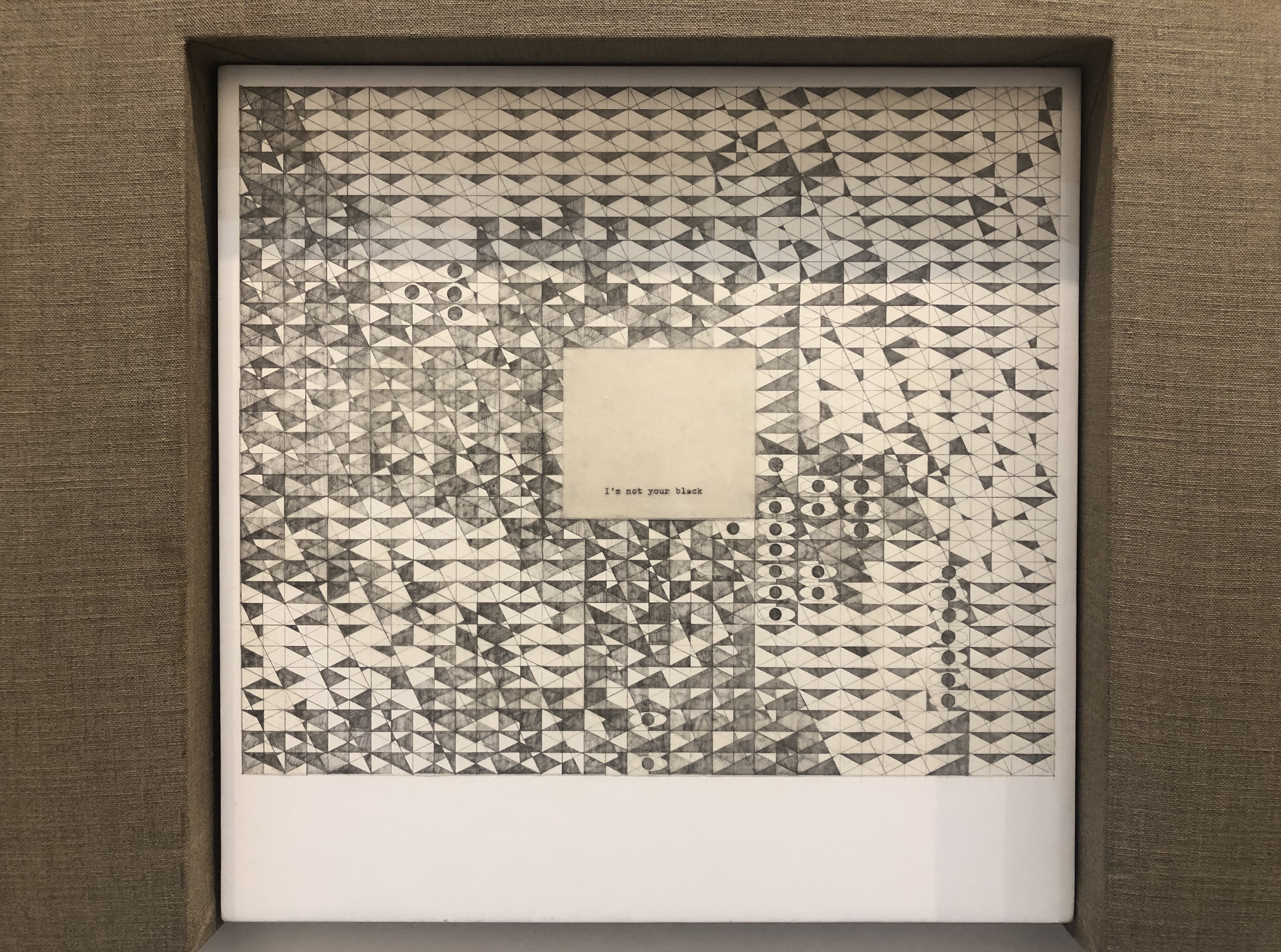

Cartografías del capital (“Cartographies of capital”) and I’m not your black, the largest-format pictures in the show, can also be read as in a kind of conjunction—as though they were just one piece—even while they contrast with one another. The first leaves exposed, almost entirely, the surface of its linen canvas; while the other is pure line invaded by geometric reproductions of luxury brand logos. Located in front of these pictures is Sistema disfuncional de escape, a chrome-plated tube with platinum-colored hairs coming out of its interior, forcing the viewer to look at these hairs almost without any distance, generating yet another form of observation that consists in having to pay attention to the floor and the wall at the same time. For their part, two ready-mades constitute other types of bodies in Mastica y traga and have different points of visibility. On the one hand, La Fuente, made from Nostalgia-brand white chocolate, is located on a fluorescent pedestal, taking on a kind of prominence in its wink at Duchamp; on the other hand, Huele a limpio (“It smells clean”), a small steam dispenser, goes by almost unnoticed underneath the stairs in Alterna.

Contrary to what one might expect from a Caribbean artist, Jiménez Santil is not interested in referring to the supposed origins of what the body means to someone from that region, nor in imagining that she must—almost like a mandate—invoke the sea, the island, or the archipelago. Her corpus puts all this to question: critiquing it, eluding it, and addressing it using other symbols, notably La Insuperable, the Dominican trap singer who defines the modulations of Mastica y traga—not only in that the exhibition is named after one of her songs, but also through her allowing another entry to be integrated into the composition of the pieces. This is evident in La mami swagger, named after part of the aforementioned song, and in Glory Hole, where we find a hole through which we can read some of that song’s lyrics. The pieces give way to claims by other types of images, such as those produced by La Insuperable, that refuse to express either submission or guilt for success.

Working within a laboratory of experimentation, the curator and the artist have managed to show how contemporary bodies are configured: not allowing for definitive conceptual answers, but instead allowing for imprints of combinations of the singular and the popular, brought together in each picture’s material composition.

Published on October 4 2019