Interview

Keeping the Reds: Interview with Cosa Rapozo

by Mariel Vela

The artist opens the doors of her studio during Material art fair

Reading time

9 min

For its eighth edition, the Material fair changes venue. Calle Sabino 369 will open its doors to receive artists and galleries from different parts of the world. The new location distinguishes Santa María la Ribera, San Rafael, and Atlampa as neighborhoods that, owing to their innumerable studios and cultural organizations, have become essential to the art scene in Mexico City.

As part of the fair’s Invited program, Mariel Vela visited and interviewed two artists working in the area: Cosa Rapozo (Guanajuato, 1987) and Benjamín Torres (Mexico City, 1969); the latter presents new pieces at the Pequod Co. booth.

Cosa Rapozo guides me to the back of a shared space. Before arriving at her studio, she tells me, “This is Enrique, this is Hernán.” I sense a complicity among the three that is foreign to me, and of which for a moment I want to be part: If you tell me your secrets, I’ll tell you mine. Modesty is a feeling that moves one not to tell others about certain feelings, thoughts, or acts that are considered intimate. Upon transcribing the audio of this interview, I notice the first seconds in which the nervous laughter between us, two strangers willing to talk about their things, is recorded.

Mariel Vela: I recall from reading the gallery text of the exhibition La vergüenza vino después [The Shame Came Later] at Galería Libertad that you mentioned the section “Trágame tierra” [“Swallow Me, Earth”] of the teen magazine Tú, which in the 90s published embarrassing stories that the readers themselves sent to the magazine’s editorial team. I like how you take up anecdotes of shame as a literary, discursive, and emotional force. When do you think shame came into your life?

Cosa Rapozo: I think I started exploring this as a conscious thing during the pandemic, since I suddenly felt a need to get out, and not necessarily out of the physical space that I inhabited like everyone else throughout forced isolation. Rather, I felt that there were experiences from my past that needed to come out and to be pronounced. This confinement that I already had inside and that had been going on forever became evident once there was a parallel with that physical confinement. That’s where the reflection comes from, but all this also arises from a curiosity to know whether this shame was learned, or whether it was just a physiological reaction. These two fields are always trying to mediate an immediate reaction that you as a social person might have when faced with a situation. You might think of a learned or an acquired shame because you know that you look ashamed in front of another figure. If the same thing happens to you and there’s no other figure in front of you, are you still ashamed?

I think of the interior time folded up in me, of how I go back all the time to childhood or to adolescent experiences in order to try to find the moment when something opened up in me for the first time. It’s difficult to trace a memory that might store the origin of shame or desire. We talk about the importance of making comparisons between our own sensibilities and the sensibilities of others, a practice that has not ceased since our arrivals in Mexico City: hers since Dolores, mine since Tampico. I also recall the arrival of María Luisa Puga from Acapulco: “The internal silence that formed in oneself when faced with the awareness of seeing, of being seen, of being at the same time as others.”*1

CR: It’s strange. How does one respond to things that in your adolescence you couldn’t solve because there weren’t any tools? I was born in a town called Dolores, in Hidalgo. There’s a thing imposed there that you don’t take into account until after you leave. I haven’t lived in Mexico City very long, only a little over a year and a half. The reality of a plural context or a context that calls itself plural and cosmopolitan is light years away from what can be lived at this very moment in a town like the one I grew up in, so I still feel like I have a timeline that’s a little outdated. I want to give a chance to all those things that couldn’t come out in an organic way, and to stretch them out using those things I do. But it’s very weird for it all to return suddenly… To see, to try to see with other people’s eyes: how do you see me? Because the way they see me constructs me, and above all constructs the visuality of what I do.

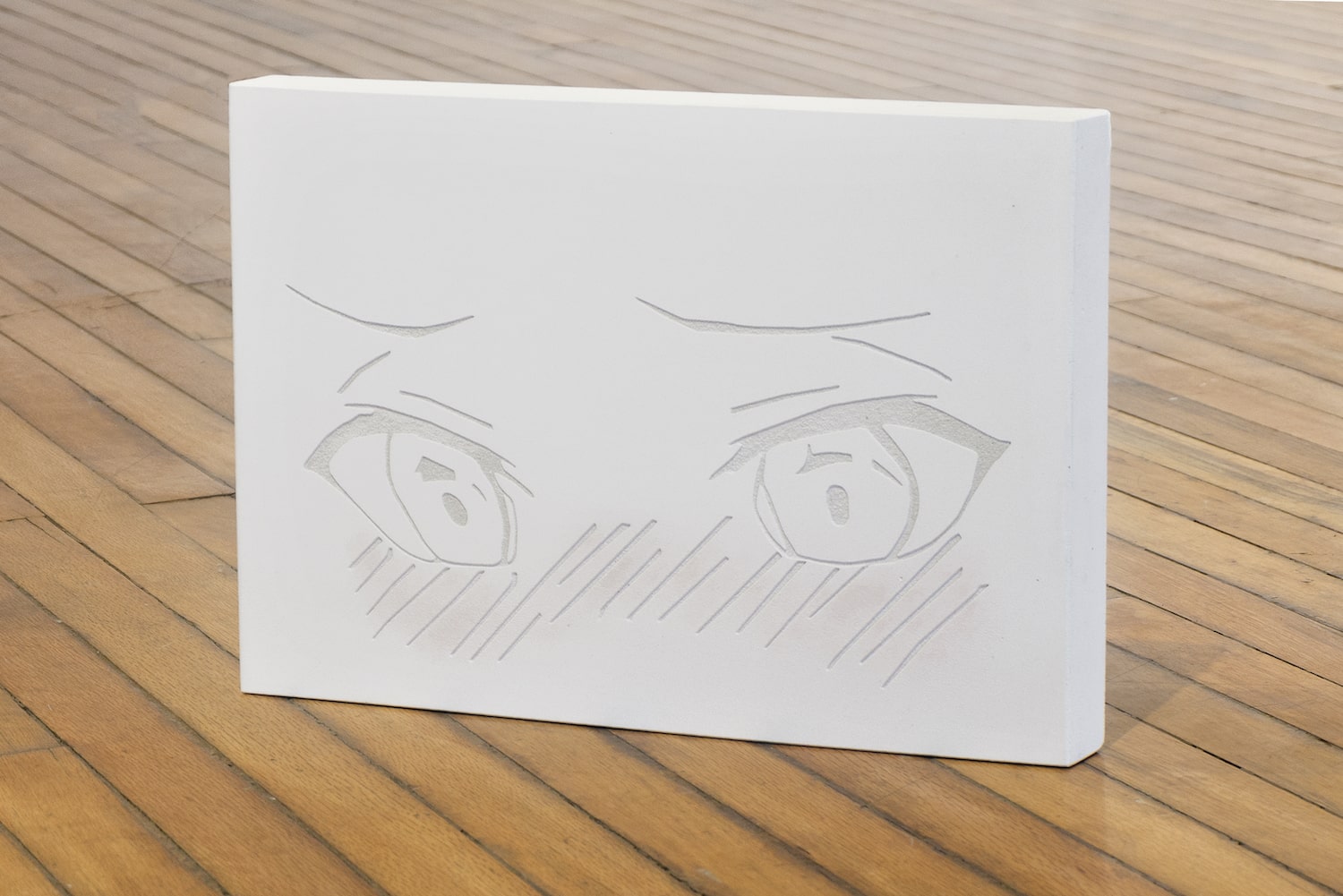

At the back of her studio I see the three narratives presented on rolls of fabric as part of the project NUEVA SUCURSAL [NEW BRANCH OFFICE]: “Tus ojos sobre mí: shame on me” [“Your eyes on me: shame on me”], “Vestir la vergüenza” [“Dressing the shame”], and “Instante de la susceptibilidad y el trance” [“Instant susceptibility and trance”]. Disney princesses are in distressed and vulnerable states. I realize that Cosa performs an archeology of the gestures embodying that feeling of being looked at when we don’t necessarily want to be looked at: she traces their repetition.

CR: What came first: the representation of shame or shame’s reaction? How does one represent blushing? The tiny stripes and red of anime, for example. The body wants to project what you’re trying to invalidate or repress, and in that repression there are inevitable outlets. From that embarrassed figure, I thought about the relational point of two figures. For example: jealousy. The performance of jealousy is something that’s already given. Sometimes it’s hard to separate out those inner scripts from your everyday mechanism.

MV: Is there something in my body that triggers a chemical reaction or is it something learned? Maybe it’s a combination of the two? I remember that in kindergarten the boy I liked would pass by and I would lay on the grass, trying to recreate in my body all the faded princesses I had seen in the movies: an implicit and intuited beauty in those representations of female vulnerability. The image possesses you, and you perform that theater of emotions; you activate that inner script you were talking about.

CR: Exactly, there’s an incitement! You ask for it to be put into play: that sequence, that scene, based in the gestures you replicate. One understands it very quickly.

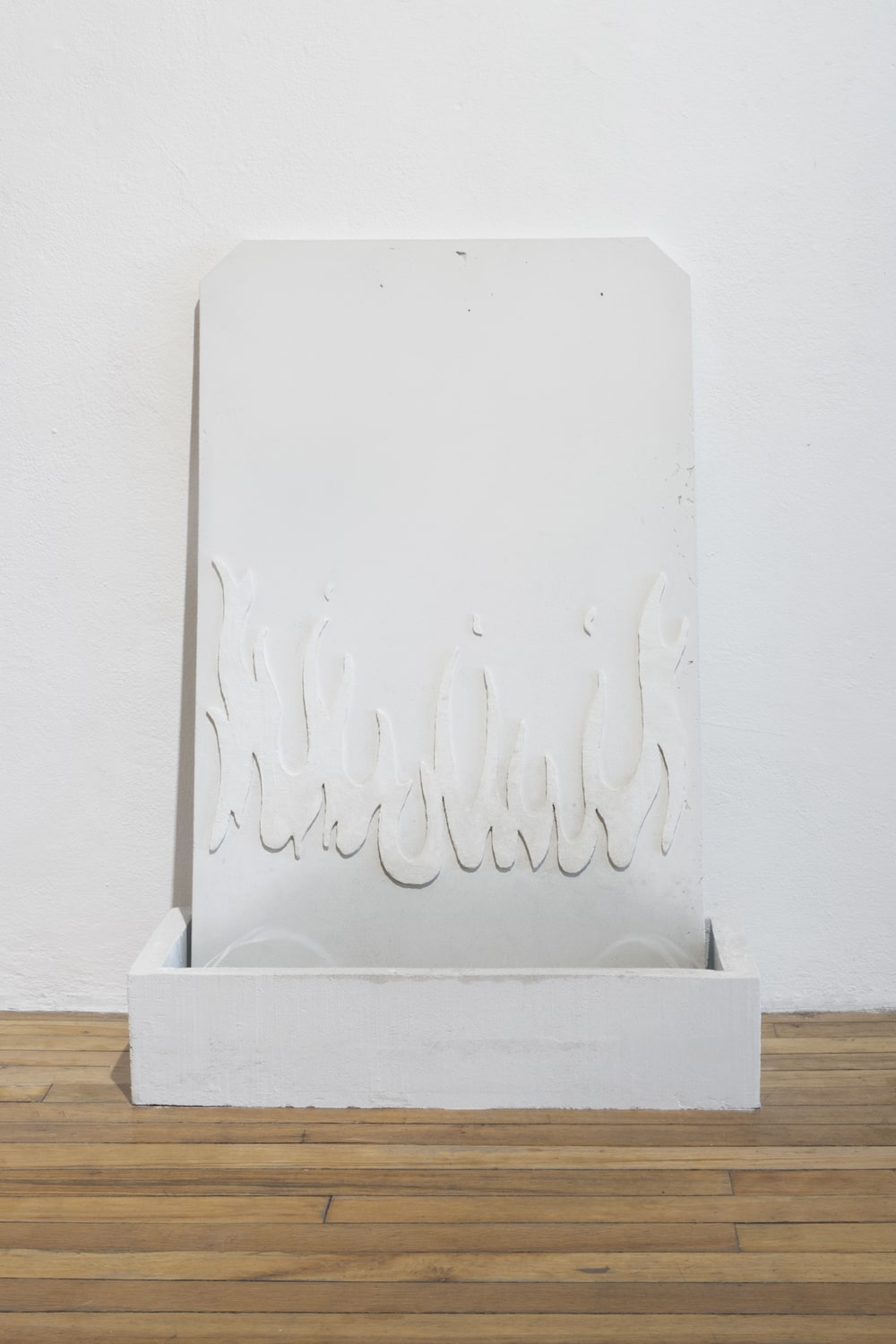

We begin talking about her love for fountains: literary fountains [fuentes, also meaning sources], metaphorical fountains, fountains from which mezcal flows in place of water: also that expression of ir a la fuente [going to the source], to be satisfied, to search for a lost youth. “To blush with shame is to burn inside. Will it help to put your head in water?”*2. On an internet page I found the poem “Vergüenza” [“Shame”] by Gabriela Mistral; I then scrolled down to read the user comments, and there was one that said: “[...] about the red face thing, I mean that moment, very hot and very pretty.” We talk about Berta García Faet, about red moments, about adolescents:

I would like to put all the boys

that I have kissed

since the year 1999

in the same room

and to kiss all the boys again

that I want again to kiss

and to kiss on the cheeks (or maybe on the foreheads)

of those I no longer love

and to say to the boys whose names I don’t remember

hi kid what’s your name?

and to say to the boys whose names I haven’t forgotten

I haven’t forgotten your name, seriously, I haven’t forgotten

your name

[...]

and to say nothing for 3 or 4 minutes

and that they be a little surprised

that I say nothing

and then to say very softly, at just the right moment,

let the party begin

I would like them to have a great time

drinking punch-cliché and eating sandwiches-cliché

[and dancing]*3

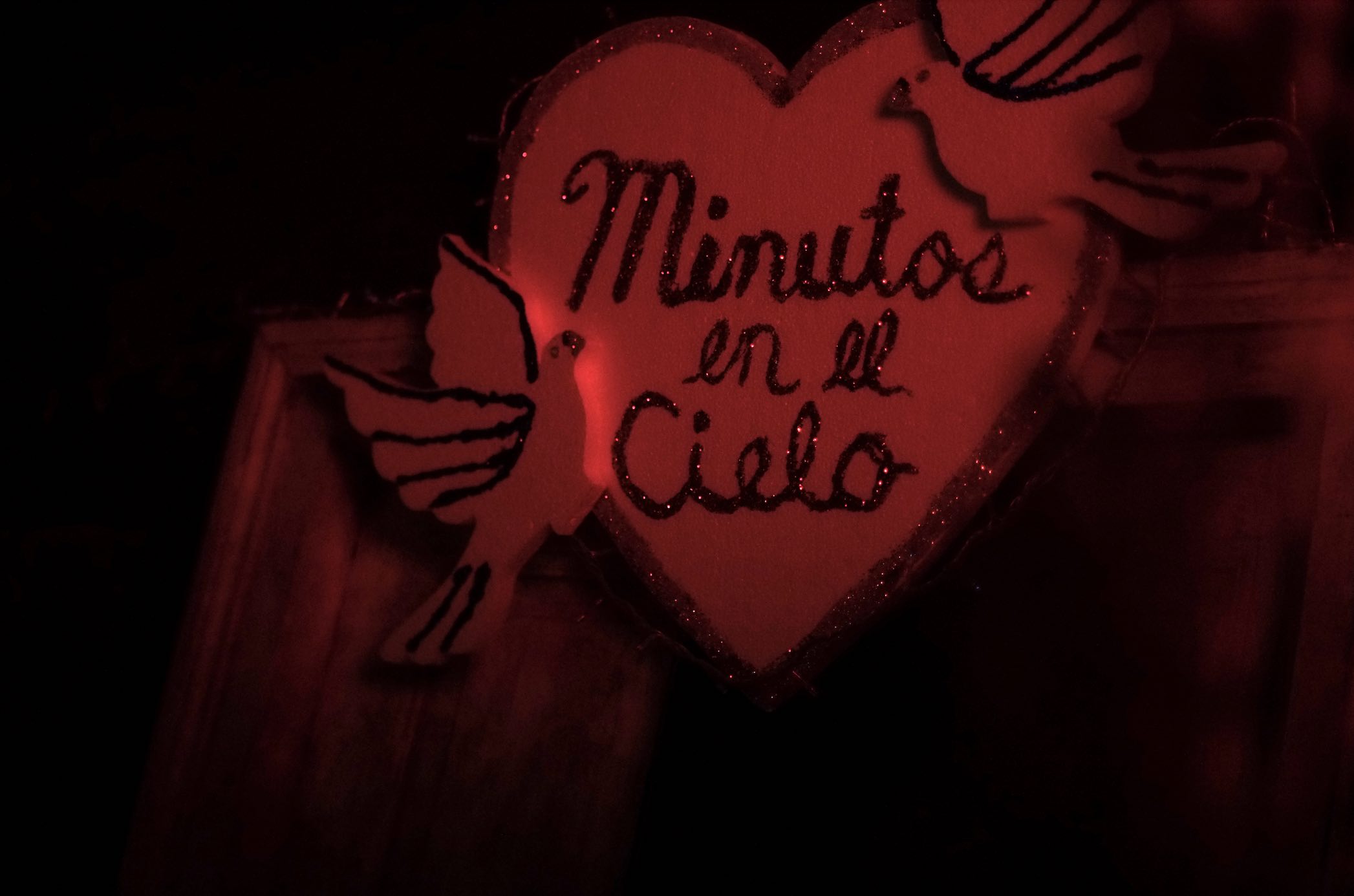

CR: When I read this poem by Berta García Faet, it caught my attention that it had to do with locking up, with keeping, with hiding. Minutos en el cielo ([Minutes in Heaven], 2019), the piece inspired in part by this poem, is a combination of nostalgia for an era and an inflated youth, eager for things to happen. When I had read this poem, I read it with a friend, and we were both very interested in exploring and in getting lost in daydreams. With this piece there was the possibility of inserting a performance, an action of incitement towards the people who attended the event. We linked the mezcal fountain, which was outside, to a dark room called “Minutes in Heaven.” At that time there was a need or an interest in returning to gestures from the past, attitudes that are no longer held to enhance daily life with daydreaming. With what once was. I still think a lot about that poem. You can get to know yourself from locking things inside you, from keeping objects or sensations that later come out. It’s a way of knowing oneself and of not knowing oneself via time.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: Translated from María Luisa Puga, La Forma Del Silencio (Mexico City: Grupo Editorial Siglo Veintiuno, 1987), p. 60.

*2: Translated from the gallery text for La vergüenza vino después (2021) by Cosa Rapozo at Galería Libertad, Querétaro.

*3: Translated from Berta García Faet, Me gustaría meter a todos los chicos que he besado desde el año 1999 en una misma habitación en Identikit, Muestra de poesía española reciente (Madrid, 2016), pp. 146 - 153.

Published on April 30 2022