Interview

Interview with Rodrigo Echeverría (or Juárez Market)

by Sofía Ortiz

Reading time

6 min

Rodrigo was alert to my arrival, looking out from the balcony of a large house in Colonia Juárez. I had written to him a few weeks prior to see if he cared if we met in person; I only knew his work from photos and I wanted to do this interview face-to-face. He came down to let me in. We greeted each other from slightly afar and then he poured gel onto a piece of cardboard on the floor so that I could scrape my sneakers into it. I thought about how some dogs, after having finished pissing, paw into the newly marked territory.

The pandemic sharpens the edges between things. For example, the new rituals in the doorway—the masks, the gel, the red dot on the forehead—make more blatant the transition between one space and another. The word ‘umbral’ (Spanish for doorway or threshold) has roots in limnis (end) as well as in umbra (shadow) and lumbra (fire): the doorway is a twilight. I’m standing right on that border, with those sticky sneakers, when I catch a glimpse of a figure with a candle.

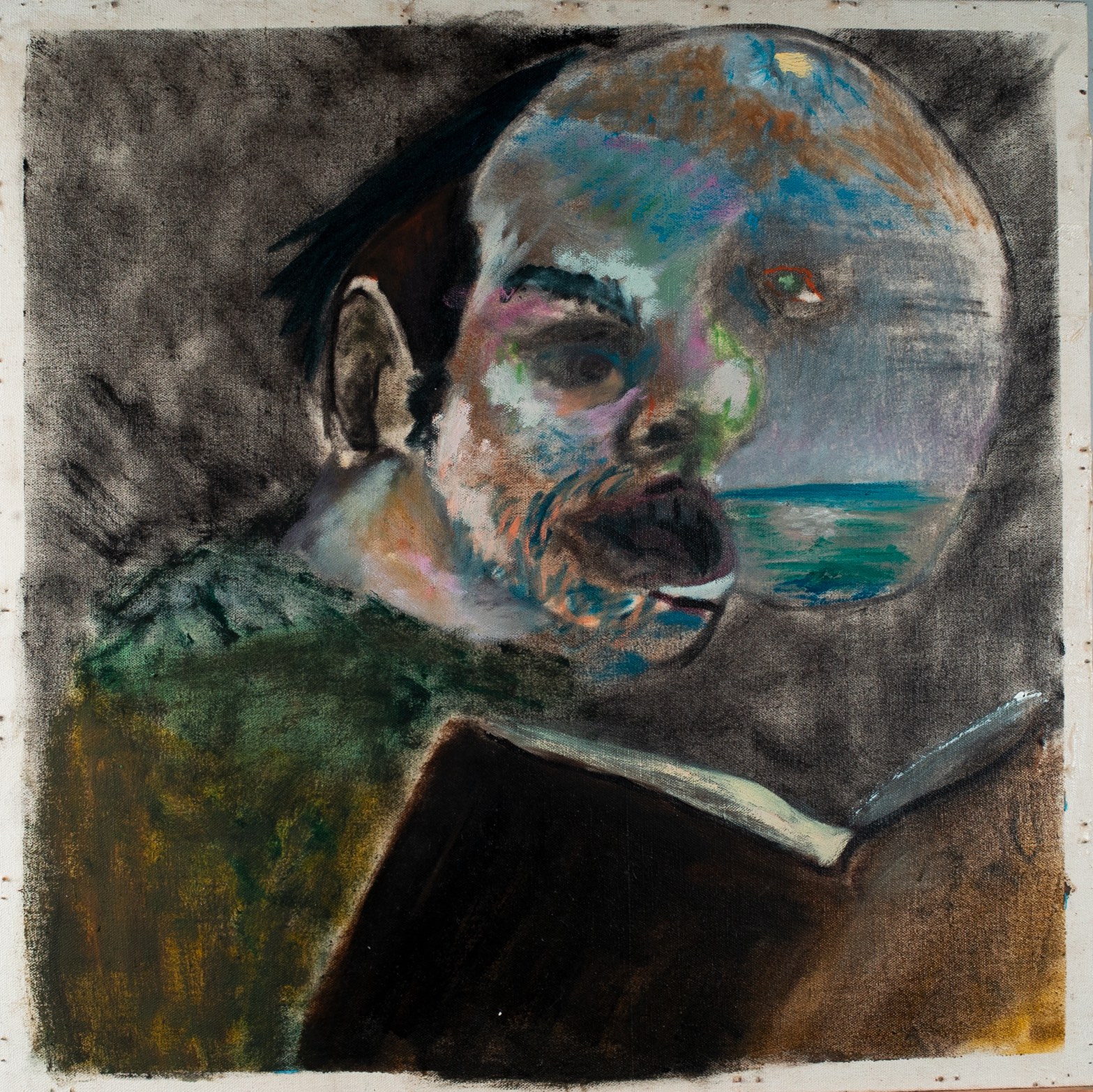

Rodrigo Echeverría: My pictures go towards phenomenological exploration. In this I wanted to portray the light of an indigent person, who in turn is a spectral presence. First, from the phenomenon of a light that appears; then, from the privilege of the span of thought, that is, from the privilege of having time and mental space to consider it. Painting, if one is honest in the work, is an excavation in the dark in order to find truth, like in Jurassic Park.

I understand what he’s saying: on the one hand, I also paint pictures; on the other, I recently saw the movie once again. There’s a scene where a scientist in a white coat (who looks like something out of a Stock Image™ file) inserts a tiny needle into a mosquito and extracts Dino DNA, the seed of enough chaos for several movies more. In this, art is like science fiction; the question isn’t what we’ll find, but to what extent it can get out of our hands.

I pass the doorway into a room with two couches, a skylight, and a betta fish in a tank full of snails. Rodrigo says he doesn’t know how the snails got there, and it crosses my mind that, for hundreds of years, in the west we believed in spontaneous generation: flies were born from meat and ducks from trees. Throughout our conversation, I begin to suspect that what this painter really wants is to get the picture to paint itself, to suddenly appear like the snails in the tank. I imagine this scene: Rodrigo steps inside his studio, the cup of coffee in his hand slips and breaks, and the picture that was blank just the night before stands finished in front of him: a radiant immaculate conception. Rodrigo dies instantly.

RE: I want to find color’s desire, what color wants for itself, instead of me imposing myself. I stand silent in front of a picture so that I can listen to what it needs.

He points to a picture mounted on the wall.

RE: Here, for example, I imagined a red and didn’t know where to put it; I had to spend a lot of time meditating on it. That’s part of the boredom and tedium of painting. Painting as a process bores me a lot, it distresses me.

Sofía Ortiz: What do you like to paint?

RE: The sun.

SO: The light?

RE: It’s the same. I’ve been obsessed with the sun for several years. The sun alters everything, all the time: pupils, plants, shadows. In 2015, I had an episode of isolation in which I spent a lot of time alone, and I realized that the sun doesn’t go down; it’s the horizon that rises. To understand it, I began drawing my house’s patio a lot—I called it spontaneity management—in order to record how the light would alter it.

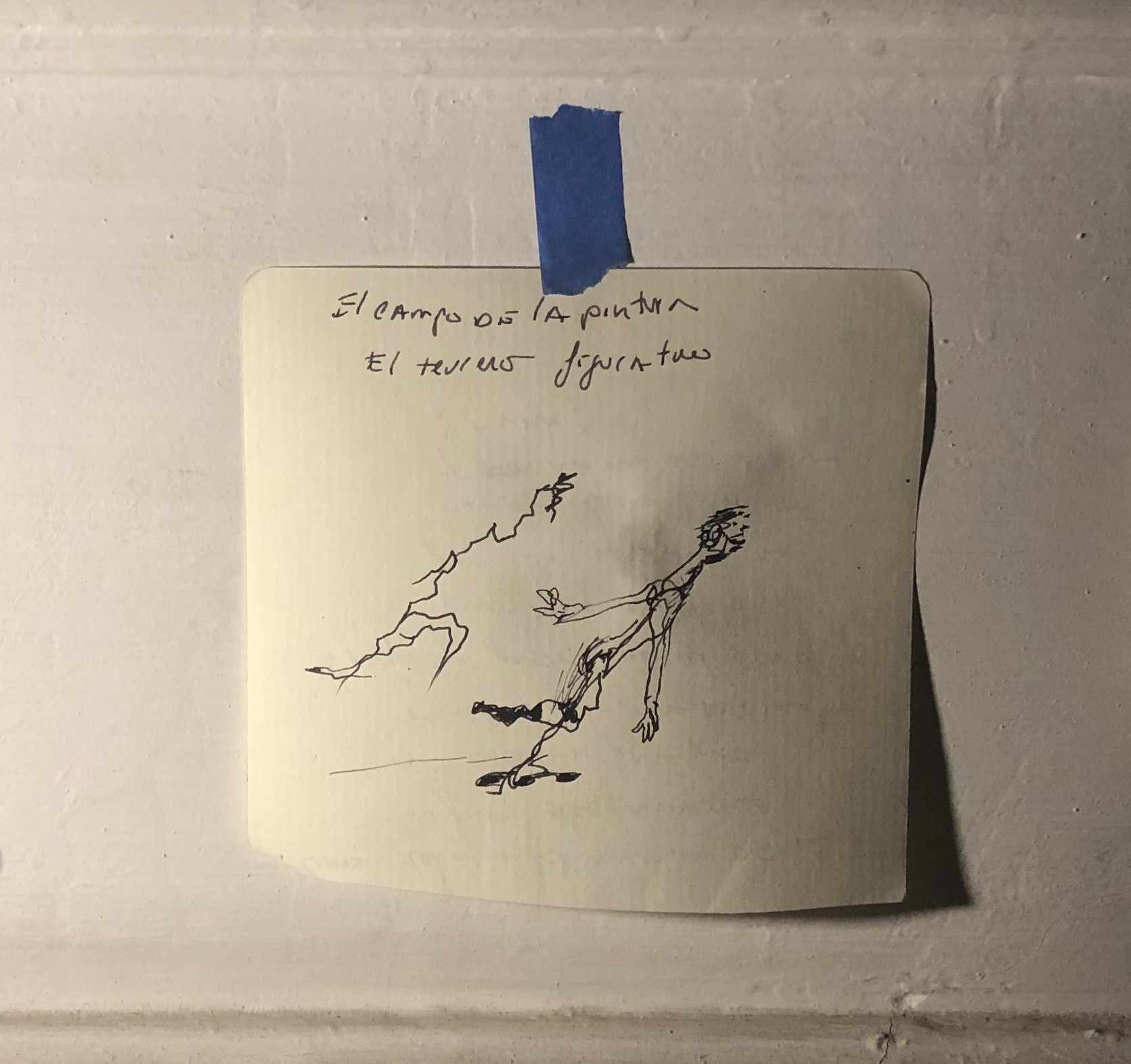

One of the rooms in his house-studio, the room where he reads and writes, is wallpapered with notebook sheets arranged in precise grids. They contain notes and drawings. I peer vaguely at them, but I feel shy; it’s like I’m reading his diary while he watches me. I take a photo almost at random:

“Not to be cheesy,” he tells me, “but, for me, God is in the line. It’s infinite and contains everything.”

He explains that he copied a crack that appeared on his wall as a result of the 2017 earthquake, something in which he afterwards found a figure. Although we all carry that impulse—I, for example, can’t see cars without seeing their headlight-eyes and mirror-ears—in Rodrigo’s case, pareidolia (the phenomenon of finding shapes, especially faces, in things) is integrated into his work process. He hardly ever uses reference photos:

“I feel redundant making a hologram of reality, instead of creating a new reality.”

I sense that what he does is listen to the picture so that it can tell him what it wants.

We continue talking and imagining. Then we speculate about how it would feel to be a painting, and if we could propose that to Pixar as a premise for a movie. Rodrigo trusts in the subjectivity of objects: he’s attuned to how the inanimate alters us.

“I’m an empiricist,” he tells me, “and I accept that I don’t control anything.”

In 2018, he carried out a residency, Haven for Artists, in Beirut. He tells me that being there changed his relationship with painting. He was in no rush to produce and, in a new context, he “had nothing to prove.” Again I understand him. I did a residency a few months ago that left me with the same feeling of freedom.

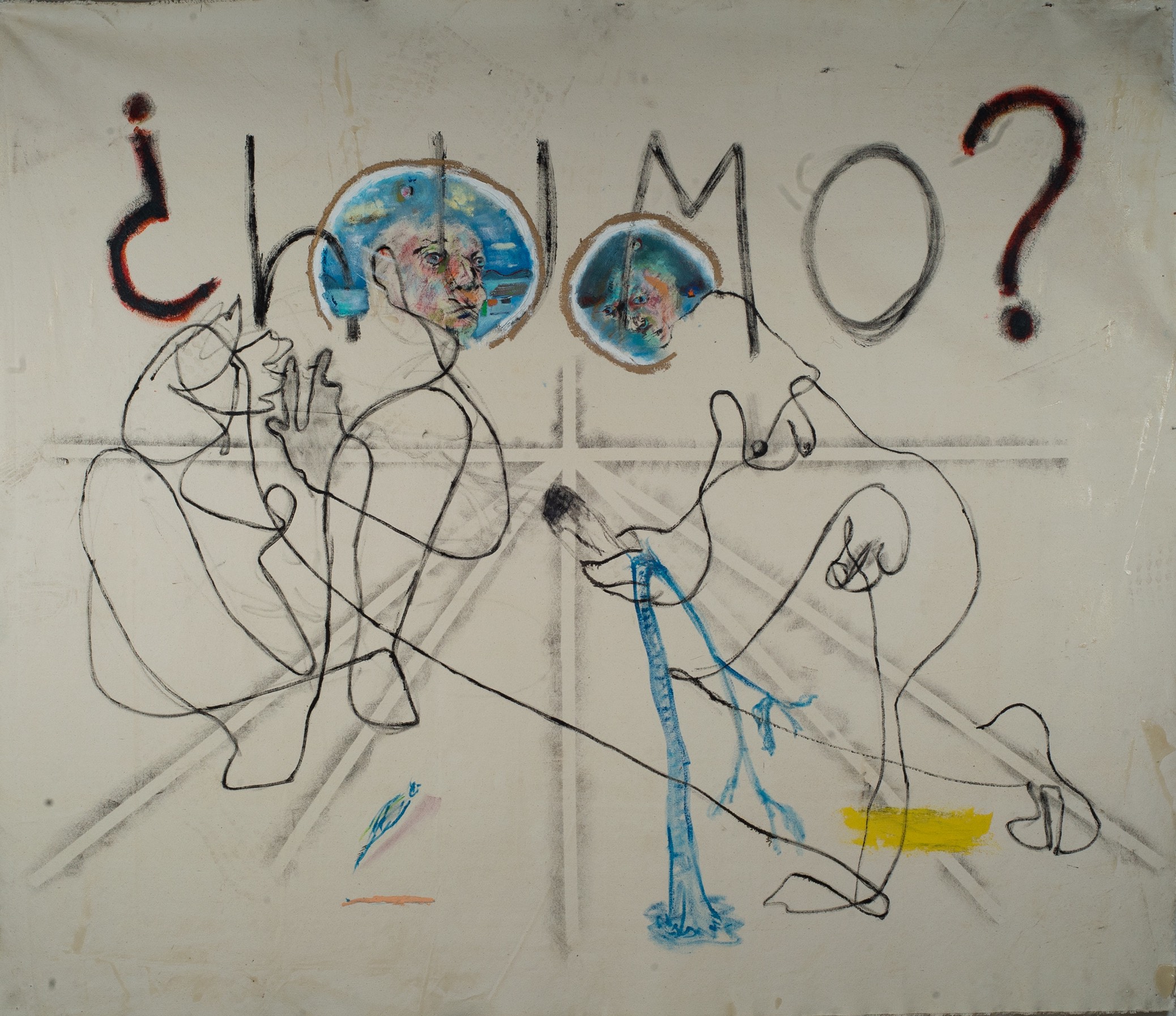

RE: I aim for the picture to pose the riddle and also hide the answer, but that’s not something I’ve succeeded in doing. I don’t really like justifying painting with words since it becomes words itself. I write a lot in order to understand what I’m doing. When I have an exhibition I like making pictorial fables more than talking about a certain contemporary context.

We could talk for much longer, but the sun is about to go down and today I’m apprehensive about walking alone the few blocks from his home to mine. We look at the Juárez market from his balcony. The awnings above the entryways are a screeching green, the same that appears in a small painting on the easel. He’s already shown me all the pictures in the studio: the portrait of his girlfriend, the choir singers, a puppy, Saint Pericles, and, my favorite, the Three Wise Men. When Rodrigo looks around him, everything is potentially art. That way of seeing moves me…and makes me feel tired. We say goodbye at the threshold.

Published on July 2 2020