Review

How much space does a dream need?: Christian Camacho at Sala GAM

by Julián Madero

Reading time

4 min

The truth is not found in a single dream, but rather is part of many dreams.

— P. P. Pasolini, Arabian Nights

For a few years now, when looking at Christian Camacho’s pieces, I happen to separate myself from my body in order to access a dislocated, intimate, and anonymous space. His pieces set off that particular metamorphosis while welcoming me in like a tiny ant, and—despite their small scale—I perceive them as enormous. I believe that this discrepancy between material presence and symbolic display belongs fundamentally to literature, and more strictly to poetry. In Christian’s work, a camel passes through the eye of a needle.

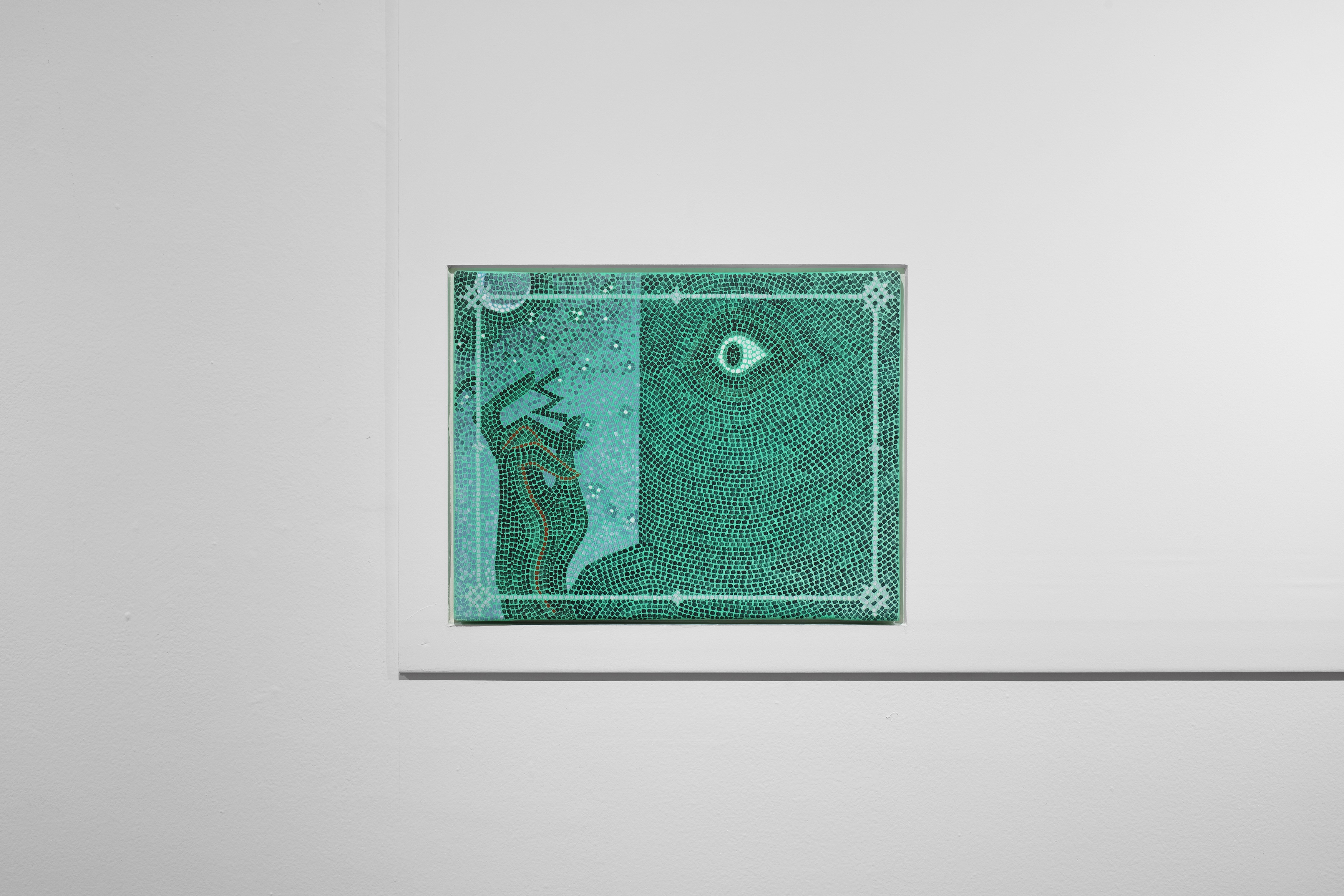

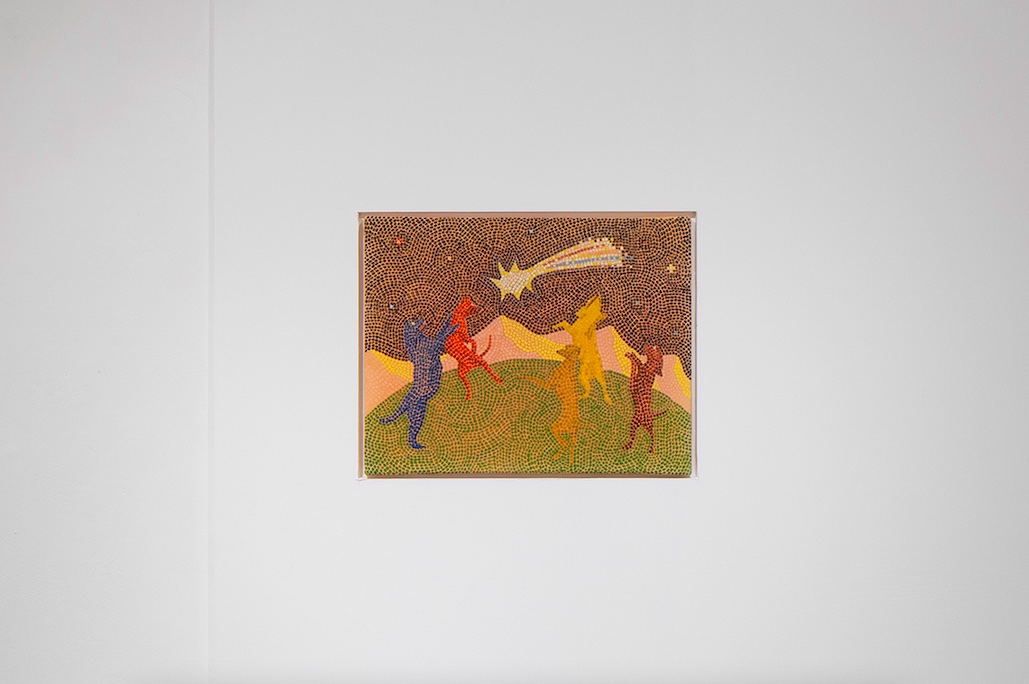

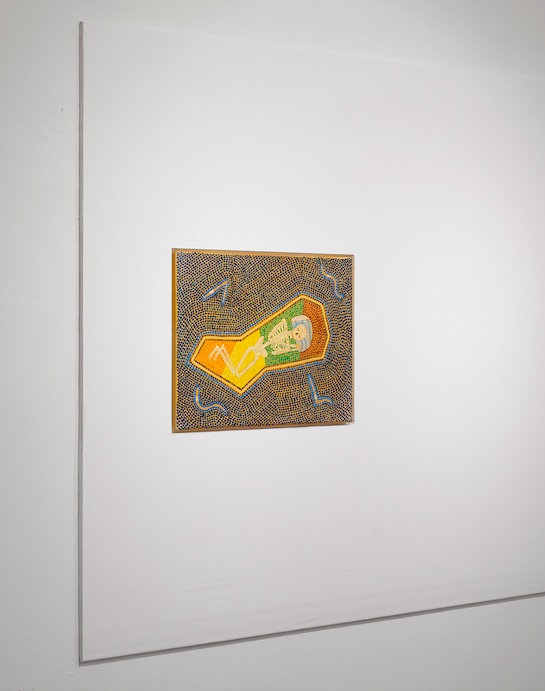

The exhibition En la vida, en la muerte y a la mitad (In Life, in Death, and a Half), currently on view at Galería de Arte Mexicano (GAM), presents nine recently produced small-format canvases. Although the mosaic motif has appeared in Christian’s work since 2019—with paintings that emulate the typical mosaic tessellation via abbreviated brushstrokes—this exhibition displays a coherent and unerring ensemble, one that shows the development of a formal and conceptual investigation regarding the mosaic-painting ratio. The pieces arranged at Sala GAM, embedded in the wall, seem modest, with plenty of space between them, so that they do not impose themselves on spectators but rather ask us to come meet them. They recall, at first glance, those museum rooms dedicated to ancient art: vestiges and documents, the daily life of extinct civilizations.

The subjects of the pieces do much the same, evoking key moments in the history of art: here, in the portrait of a woman with a cell phone in hand, we recognize the colorful Soviet; there, in that showcase of sneakers, the asàrotos òikos or Roman “unswept floor;” in that puddle, the naturalistic illustration of the nineteenth century; some mystical coven featuring dogs; a drawing that looks like the prototype of Klee-ian cosmogenesis; a mural of the nervous system as Roman divinity; a TV bumper for popularizing science; a digital folder icon in the Bauhaus style; a skeleton in its grave, peacefully asleep… historical entities swirling away, indices throwing uncertain clues.

Seen up close, each painting sets forth its uniqueness. The historical references, as well as the anecdotes of their conception, blur in the face of the joyful vibration of colors. The rhythm of the lines, with accents and finishes of tone and shade—which are in no way pixels, since they don’t obey an orthogonal nexus—dance like streamers. The sneakers dance according to a harmonic score that comes and goes, seconded by the valence that goes up and down. Brushstrokes sizzle with the sprit of detached tesserae. The dogs dance with pure taste for the peach orange that unites them. The shapes give way: the skull coffin bends to rest, assuming the semi-fetal position. And it is not Christ who looks but rather the Cyclops who, with the same Byzantine radiation, supports the E of Energy. The hand mutates and becomes a neuron that thinks.

Christian’s work opens gaps in the strata, crosses borders, and collapses the Fine Arts Department with the Stationary Department—scholarly fact with fan art. In the execution of his brushstrokes-tesserae I perceive the serene calm of someone who walks without haste. The pencil drawing of shapes and patterns, which is revealed to be subtle, apparently intuitive, without “the rule that corrects emotion” (perhaps because it has already been arranged as a rule of the game), erodes the illusion of the mural, revealing the scholastic note.

It all comes down to, or comes back to, the problem of surface: the light—or shadow—of the colors. Camacho presents himself in this series, in my opinion, as a sensitive composer who paints lullabies for a civilization in decline. We will sleep happily under its mosaics, listening to the crooning of a Russian peasant: two meters of earth, from head to toe, was all he needed.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on March 24 2023