Review

Healing with Matter and Signs: María Sosa at Llano

by M.S. Yániz

Reading time

5 min

What is the body but flesh in negotiation with the world? María Sosa (born in 1985) unfolds her body by encrypting her illnesses as historical pathologies of instrumental reason. She does so from a feminist sensibility that cares for and understands the relationship between materials and their stories. At Llano she presents El otro lado de uno mismo (The Other Part of Oneself).

The gallery becomes the sensory display of the artist, who shows her body as if in a ritual in which it is dismembered and reveals the sutures affecting it, the memories sustaining it, the myths representing it, and the desires inhabiting it. As a kind of flag or warning, before entering the ritual, one finds Tlacuacuallo “una xaqueta labrada de huesos de hombres” ([A Jacket Carved from Men’s Bones], 2021); skinny legs made of fluorescent tubes with plaster feet and dangling plastic hands hold a scarf as though it were a canvas. On the front is painted (using a gradient of cochineal pigment) a pelvis cut in half that divides the sacrum from the iliac crests, as well as a heart, a hand, a turned leg, an organ, and a face that could be Olmec. On the back, the spine and its ribs are painted, the ones on the left are broken, faded by the scarlet cochineal stain. Beneath there is both a foot and an arm. The sign is clear: you’re about to enter a mutilated body.

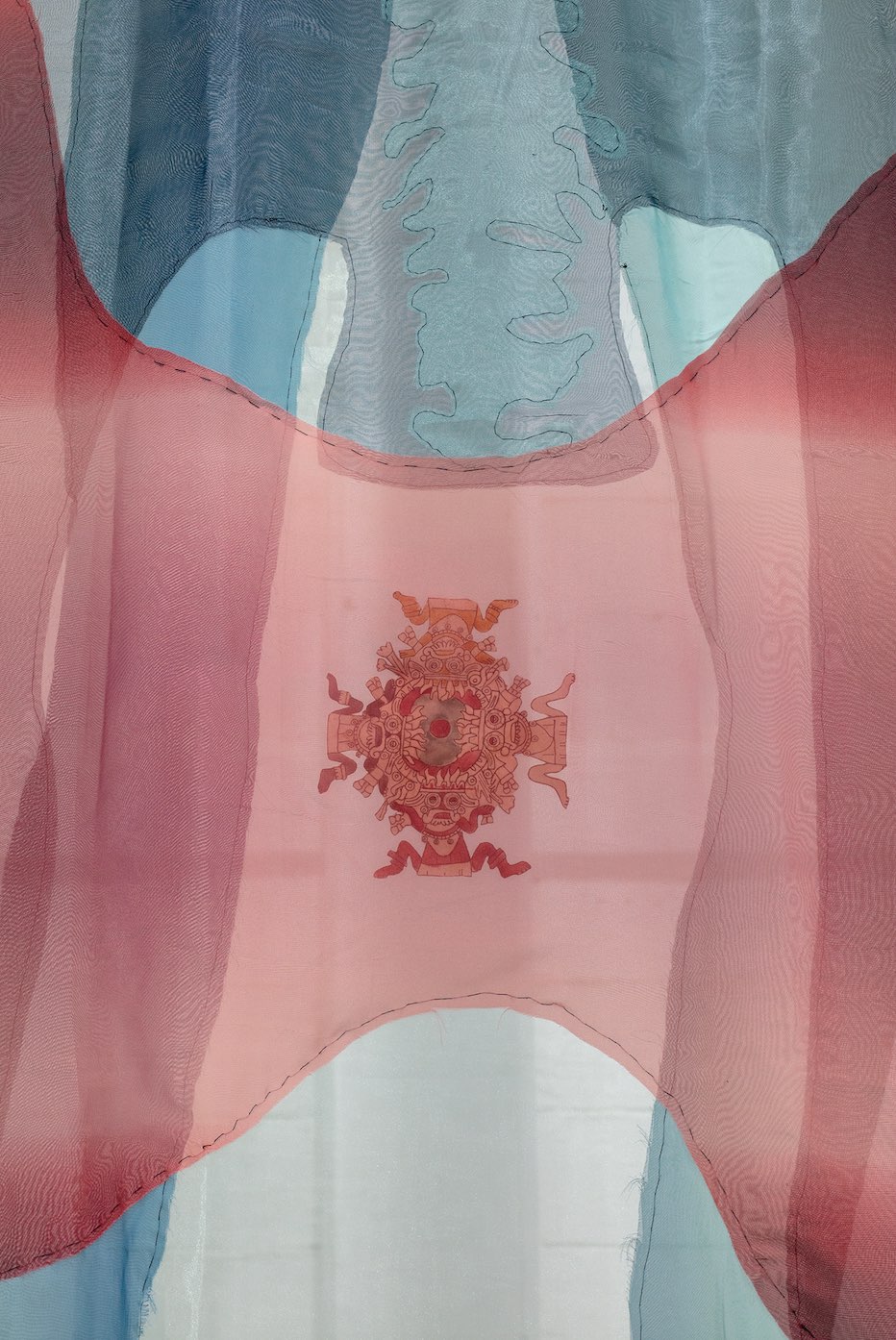

I typically think that viewing an exhibition is a kind of choreography between the eyes; walls, objects, and other bodies all have their rhythms. Sosa constructs her show by appealing to the dance of looking and feeling art. There’s no point of view for getting a complete impression of the exhibition. Using large-format canvas paintings suspended from the ceiling, it closes in on itself, creating its own space within the gallery. My first tour of the place was from the back, owing to what was possibly an intentional oversight—that is, I surrounded the exhibition by the four paintings themselves, viewing their backs. Being canvases with transparencies, I was able to tell how they were made: folds and variations of textures. Nevertheless, I could not see the paintings: for that, one has to enter the ritual and be sheltered by that small rectangle demarcating the pieces.

While going through the works, surrounding them, and seeing them up-close, I noticed pre-Hispanic iconography, figurations of body parts, costumes covered in ceramics and brass: a decomposition of being into specific mediations. There was a mystery, a not-so-obvious subtext that was brewing in the space between the canvas paintings and a wooden square that supported four ceremonial sculptures, as though indicating the cardinal points. Those sculptures had water and wind that stretched with the ceramic, as well as a pair of feet and hands hanging from the ceiling: the body was suspended between materials, stories, and emptiness.

Was I in front of an emblem, a ritual, a sacred temple, or the dismemberment of the artist’s body, longing to be reunited or distended? A game between what opens and closes. I wanted to understand, turning around the gallery and its sculpture panel, and the person I thought was the artist (I didn’t know her), talking to a famous curator. I glimpsed her as well as the pieces, hoping that this movement would reveal the secret. How can one be prepared for the ritual? What corporeal dances prepare us for immersing ourselves in ancestral experiences? What is the index of wisdom that one needs in order to heal from symbols? The body and its echoes in the pre-Columbian past have tensed up in that moment.

María Sosa was thus displaying herself as historically encrypted. The ritual consisted of the symbolic healing of her thyroid, hip, and other ailments. The exhibition aims to say that since the body is the one guiding the experience, it is necessary to understand how it has behaved and shaped our idea of the same. The symbols are an account of the ways in which the West has dominated our position, or of how the pre-Hispanic gods adopt positions that distort our idea of hominids in order to access other knowledge.

At the back of the room there was a double-channel video of María stretching and reproducing characteristic postures of pre-Columbian cultures, speculating on the idea of healing with body movements that have been forgotten, but that were carried out before the conquest of America. History is revived so that it can pass through the body of the artist. The idea is to move and live without the sedentary logic of the West. I don’t know how María Sosa is doing; I don’t know if she has healed since then. I am left with the idea that a gesture can carry history with it—upon rereading it, one positions oneself from another place, with the body changing alongside its outlines.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on November 23 2022