Essay

Excess, Pause: On "Juan José Gurrola: Todo está perdido"

by Fabiola Talavera

At Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil

Reading time

7 min

On opening day, we were late. Pepe, my boyfriend Santiago, and I had planned to venture to the museum from the central point where we had arranged to see each other for lunch. The city’s traffic didn’t yield. Everyone had already gone to a cantina in Coyoacán. When we arrived, the keepers of the place didn’t want to let us in; they were closing. Looking dismayed, we explained to them that we were part of the family and had to pass—without showing any sign of doubt. We laughed in the aisles upon entering. The visit continued swimmingly as an old television with pornographic images welcomed us.

To speak about the exhibition Todo está perdido [All Is Lost], curated by Mauricio Marcín at the Museo Carrillo Gil, is also to recall thousands of stories I have lived around Juan José Gurrola—or rather, around his legacy and those people he has personally and artistically impacted. A mystical, multidisciplinary, provocative, and seductive character. After having read thousands of documents and listened to hundreds of stories, I like to say that I know Gurrola, even though we never met in life. Although I know that his universe is much broader than what remains in his work, on paper, and in digital archives.

The tour begins with a series of Polaroids, portraits of his lovers, everyday objects, food, and landscapes: many of them intervened on using markers and chemicals that react to the photosensitive film, others shaped as anthropomorphic forms. A little further on, under a blue florescent light, a rusty piece of monobloc is preserved in an old refrigerator. The monobloc is a part of a car’s engine that for Gurrola symbolized the trade policies of U.S. imperialism, an objet trouvé from which he derived a series of photos of the streets of Bucareli, a poem, a performance, and an installation that he presented in the early seventies at the Palacio de Bellas Artes.

Gurrola had in fact trained as an architect at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) when in the mid-1950s he became involved with the avant-garde theater group Poesía en Voz Alta [Poetry Out Loud]. Although he dropped out of his studies, his interest in theater led him to obtain prestigious international fellowships in order to develop stage-design architecture.

Continuing through the exhibition, some drawings as well as images of the model of the Teatro Unitario lie in display cases. This was a project that Gurrola developed with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, in which he conceived a stage surrounded by the audience with hydraulic platforms that generated sixty-two different spatial configurations and vertical variations, providing different perspectives on the show. From then on, Gurrola spanned multiple disciplines: he shortly afterward planned happenings and participated in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s panic acts.

The first time I ever heard of Gurrola was thanks to Robarte el arte (1972), the experimental film he made with Arnaldo Cohen and Gelsen Gas, and which portrays the robbery they carried out at Harald Szeemann’s revolutionary documenta 5 in Kassel. Santiago showed it to me. Edwarda, Juan José’s daughter with Rosa, had acted in his first film, Plan Sexenal (2014). It was 2016 and I had recently arrived in Mexico City to study for my degree. I soon heard the rumor that they needed someone to help with Gurrola’s archive. I met Rosa, Rose, Rosa Vivanco, Rosa Gurrola, Newton, “a rose is a rose.” As part of our first meetings I read the book La Boîte de J. J. Gurrola (UAM, 2014) by Andrea Ferreyra, an encyclopedia of this figure who had such an impact on contemporary Mexican art. Shortly afterwards, I met Mauricio and Angélica García, and together we determined which part of the archive I would take care of. Without much of a plan at first, but with extreme eagerness, I would go to Rosa’s house once or twice a week to digitize Gurrola’s work documents. Little by little other people became involved and the documents we had to digitalize were oriented towards his work in theater. We started a fundraising campaign, celebrated an ethylic tribute in Covadonga, and we secured the support of a FONCA grant to create a digital database for public consultation.

Gurrola’s stage work is extremely vast: he fulfilled multiple roles both on- and off-stage beginning in 1957. Walking around the exhibition, the names of some of the works evoke for me memories of days in the archive reading press notes, checking the dates on the backs of images, cleaning off dust, as well as numbering and scanning each old piece of paper while we drank tea and heard anecdotes from the participants. Los buenos estragos (1970), regarded as the shortest play in the world, with a duration of only 15 seconds, consists of an act in which the magician Trébole (“Clover”) tries to solve a mathematical puzzle while a naked woman gets up from a chaise longue and laughs at him. In 2020, Pepe Romero created Los nuevos estragos for the Festival Poesía en Voz Alta, a video-act produced using the same instructions, as well as some other musical pieces and many nude scenes, which again confronts both rational and erotic forces.

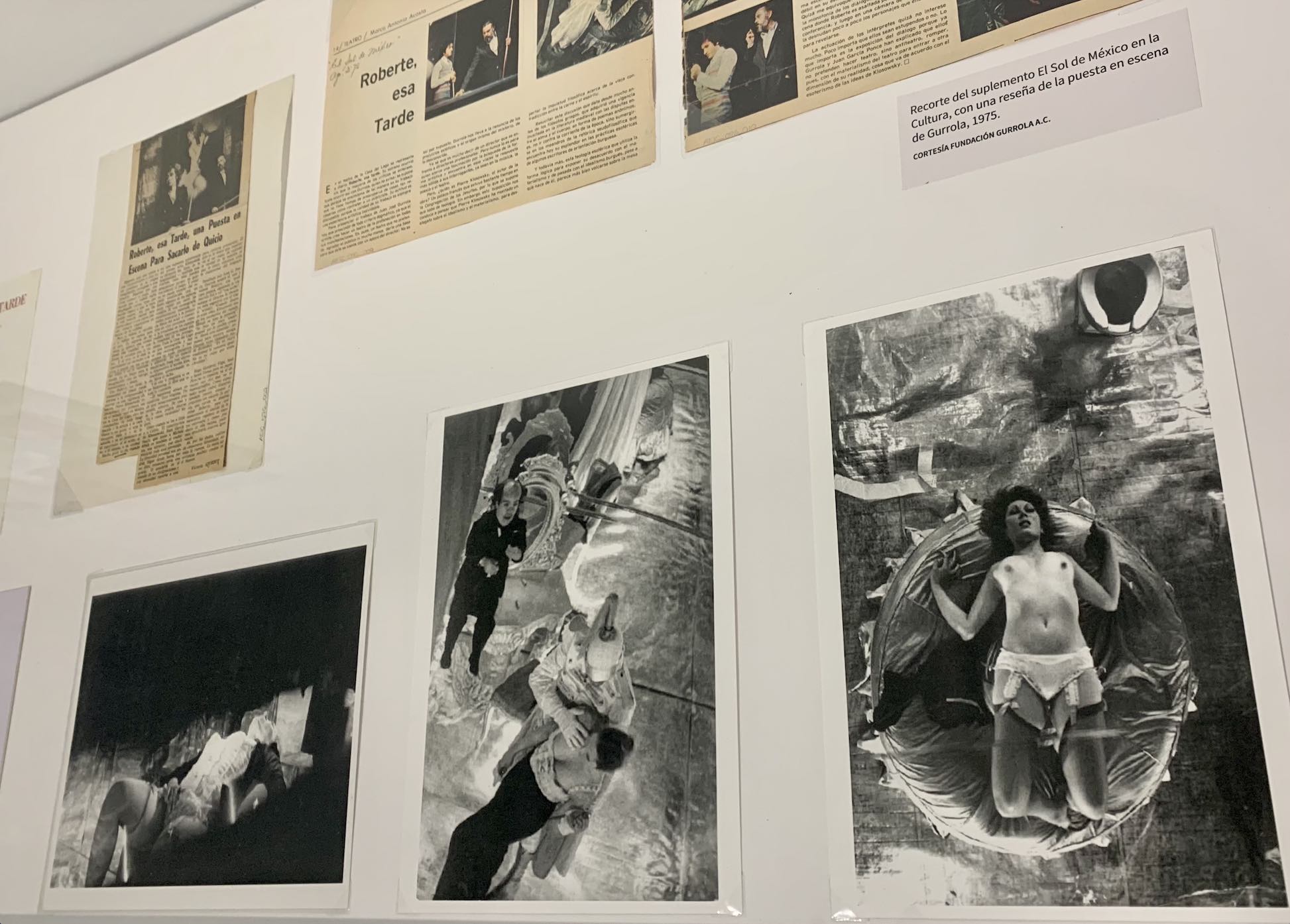

Roberte, esa tarde (1975), an adaptation of a text by Pierre Klossowski, presents a voyeuristic plot consisting of perverse games of pleasure between a married couple and their guests. Based on some twisted laws of hospitality, Gurrola created for this staging, which took place at the Casa del Lago, a set design in the manner of Duchamp’s Étant Donnés, in which the spectator could look through a peephole into a room of 12 x 12 meters, upholstered with mirroring paper. In it, a woman, played by Monterrey actress Fuensanta Zertuche, engaged in intimate relations with different individuals.

Many of his drawings and paintings arose from his research into the works he staged, such as with Pasiphaë, the zoophilic myth of a woman who falls in love with a beautiful bull. As in this case, much of his work uses eroticism and pornography as theoretical frameworks for challenging the morality of his time: a radical position that praised female sexual agency and that saw sex as an act of enjoyment that could momentarily suspend our inevitable deaths.

Something that catches my attention is a phrase by the artist, found at the end of a gallery card, next to two paintings of women with their legs open who touch themselves joyfully with the fingers of their painted nails, Madame Edwarda I and II. It says: “To be frank, what I want with those acrylics and drawings is to tell everyone: Fuck!” In other works, with a Gustonian style and observant eyes, he would portray everyday scenes from his context, which generated a style of painting that was “Super-Mexican [mexicanaza], cheap [guarra], trashy [ramplona], bawdy [alburera], and twisted [chanflera],” in the artist’s words.

On the other hand, in Dom Art, he mocks the bourgeois commodities of the prototypical North American family: wedding ring, pancakes, Kool-Aid. As Marcín rightly points out in the curatorial text, Gurrola, a man of the theater, conscious of lies and of performativity, knew that political forms, the morality of an era, good taste, and sexuality were ultimately transitory, authoritarian, and relative.

Even though the show’s title denotes a strong nihilism—All Is Lost—and even though we only shared space and not time, it seems to me that Gurrola was above all a lover of life. An example of an existence rich in experiences and a trajectory that walked almost all artistic paths that can be explored, that refused to fall into pigeonholes and mental totalitarianisms that seek to silence rebellious souls. Excess, pause, a modus operandi of periods of life’s absorption and moments of creative reflection. Excess, pause.

The exhibition can be visited until April 3, 2022 at the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil.

Published on January 29 2022