Essay

Estudio Acme and Estación Material Vol.3: On Frontal Forms and Certain Escapes that Break Global Mannerism

by Sandra Sánchez

Reading time

12 min

1.

Forms everywhere. Let's suspend the division between figurative forms and abstract forms.

Let’s think for a moment about forms derived from practices and forms derived from concepts.

2.

Thinking about forms as derived from practices or concepts aligns with the display of pieces at Estudio Acme: the itinerant extension of Salón Acme—this time at the Museo de Arte de Zapopan (MAZ)—which, until October 10, presented works by 86 artists who have participated in the fair.

The pieces were selected by an “artistic council” that asked artists who had previously participated in Salón Acme for a list of available works. The council was composed of Eduardo Sarabia, Fernando Palomar, Francisco Ugarte, Gonzalo Lebrija, Jorge Méndez Blake, José Dávila, and Mónica Escutia, who participated in the first State Guest: Jalisco, at Salón Acme No. 1, in 2013.

In Estudio Acme, the works are for sale, which broadens the museum’s critical function as a public sphere for exhibition, discussion, and/or collection, to a space where economic transactions between collectors and artists are possible. The museum has never been a neutral place; the white cube is a visibility device where what is shown is declared and justified as art based on power-related parameters, like any other device where something visible circulates through a series of statements. However, in museum discourse, selection criteria respond to programs (state, university, or private), subject to public discussion (debatable). As the philosopher of art Boris Groys says, the curator plays a singular mediating role:

“But art’s freedom means different things to a curator and to an artist. As I have mentioned, the curator – including the so-called independent curator – ultimately chooses in the name of the democratic public. Actually, in order to be responsible toward the public, a curator does not need to be part of any fixed institution: he or she is already an institution by definition. Accordingly, the curator has an obligation to publicly justify his or her choices –and it can happen that the curator fails to do so.”¹

When the figure of the curator is replaced by an artistic council, the possibility of public discussion about the selection criteria is lost.

3.

Estudio Acme responds to a local monetary and libidinal economy in which artists and the current ecosystem need to experiment with other forms of circulation and consumption.

Rumors (((A gallerist friend keeps telling me that the market is going downhill, that galleries globally are closing, that artists are inflated and quickly end up in the secondary market, giving me examples; another colleague, from a prestigious national gallery, tells me that before, anything could be done, nothing was impossible for the gallery—now, not so much.)))

As part of the art circuit, I am happy that artists are selling, that my friends and colleagues can continue paying for their studios, their research, their lives. However, I do want to point out the relevance of the museum as an institution that accounts for a series of relevant knowledge and practices for its community (which is always subject to critique), and my caution about this shifting to a system where the market (or the “artistic council”) mediates selection criteria—especially when that council has a similar production line and an imbalance of its members in terms of gender and ethical-aesthetic interests.

That said, I find it interesting and relevant that Estudio Acme has brought together the work of artists whose practices have been present inside and outside the fair for the past eleven years. Can a fair reflect on what it has exhibited and the constants of the production it has driven?

While this was not the primary intention of the studio, it was undoubtedly one of the issues that caught my attention the most—especially in a landscape where museums rarely review local art without a curatorial research theme pre-established by the interests of curators rather than by the productions of communities in each locality.

While curatorial research—such as that of Sol Henaro at the MUAC, Karol Wolley Reyes at Museo Chopo, Mayra Vineya at Museo Raúl Anguiano, Humberto Moro and Andrés Valtierra at Museo Tamayo, or Galería 1 at Museo Jumex—has reviewed and exhibited emerging or mid-career local artists through premeditated and/or critical frameworks, the alarming thing is that since Yo sé que tu padre no entiende mi lenguaje modelno, curated at MUAC by Amanda de la Garza, Aline Hernández, and Alejandra Labastida in 2014, there hasn’t been a review attempting to account for what is happening in terms of interests, pathos, problems, and forms in the current landscape. That is, curations that don’t go out searching for works with a theme in mind but rather go to the scene to analyze the constants, symptoms, and interests of the different communities intertwined in the contemporary art scene.

I bring up Yo sé que tu padre no entiende mi lenguaje modelno because, at least in its intention, it was made explicit that “it was not a thematic curation, nor did it seek to provide an exhaustive mapping of the production of this [post-85] generation, but rather an exercise in spontaneous dialogue with the variety of reflections triggered by the works that comprise it.”² The exhibition included the work of emerging artists (at that time) like Alicia Medina, Julián Madero, Cecilia Barreto, Omar Vega Macotela, Noé Martínez, María Sosa Gabriel Cazares, Chantal Peñalosa, Jazael Olguín Zapata, Juan Caloca, Víctor del Moral Rivera, Yollotl Manuel Gómez-Alvarado, Emiliano Rocha Minter, Leslie García, and Cinthia Mendoça. Of course, there were biases—an evidently centralist one—but it was a relevant initiative to review, discuss, and mobilize current and local artworks.

What is our contemporary artistic and curatorial production proposing, from where, with what language, forms, and actions?

One thing is to curate exhibitions based on what is being produced, and another is to curate essays where certain works are selected as part of a pre-themed investigation. I’m not saying one model is better than the other. It’s just that there’s little work from the first model in museums.

I visited Estudio Acme thinking that while its exhibition and circulation bias consists of certain opacity in the criteria of the “artistic council” and its own monetary purpose (which could be tied to the production of certain forms—see section 4), this doesn’t contradict the possibility of walking through a sample of what various artists have been producing in different parts of Mexico over the past eleven years.

Notably, during the weekend that inaugurated Estudio Acme, Estación Material Vol.3 also opened (September 26 to 29) at Plataforma. Its program includes Proyectos, “a special two-year program created to support artist-run contemporary art organizations in Mexico,”³ presenting six organizations from different states. Proyectos includes mentorships from various curators.

Interlude

Proyectos was my happy place because the works not only reflected the perspectives of their respective spaces but also crafted imaginaries, forms, and processes that address (or invent) the territory and/or pathos where they are produced. It felt less like an importation of global mannerisms (((finally!!!))) and more like a series of ethical-aesthetic, material, and bodily questions and elaborations. Among them, Yutindudi (Sierra Mixteca, Oaxaca) presented Hijo del rayo: a curatorship commissioning various chintetes, traditional toys that ranged from drawings to sound pieces. Planta Libre (Mexicali, Baja California) displayed works by several artists, including Guadalupe Alonso Vidal (Ensenada, 1995), who moves between labor, animal figures linked to transtemporal iconologies, and (risky) play, resulting in a production that redistributes relationships between bodies and spaces—whether through drawing (very cool drawings, to be honest), writing, and/or sculpture. Finally, the space of Sala de Espera (Tijuana, Baja California) was an installation in itself. It pulled you out of the white wall and the black hole, making you want to sit down, chat, and put on some music. Carlos Iván Hernández’s Porohui (an animal tail that occasionally moved, placed on a bar table) worked well at the fair and on Instagram; a beauty, a very strange thing—it stirred feelings. But the surprise was Pilar Cordoba Longar’s work. Although her production is often associated with weaving, she presented the image of a truck head intervened with colorful lights, condensing an entire economy, a reality—its musicality—and its escapes. I regretted not having time to visit the contemporary art and life collective Hooogar, a regular stop in my Guadalajara visits, with proposals reminding me of the projects just described.

4.

Let’s think for a moment about forms derived from practices and forms derived from concepts.

Both the works commissioned for the MAZ courtyards from Renée Abaroa, Sonia Bandura, Temoc Camacho, César Castillo, Aquí Lejos, Milo Medina, Luisa Mendoza, Daniela Ramírez, Mauricio Vázquez, and Bruno Viruete (which were only exhibited during Estación Material week), as well as the 86 pieces in the Grand Salon (which remained until October 10), shared a common concern for form. I am not pointing to an inherent modern formalism, nor to an exploration of a neutral or universal form; rather, most of the pieces were centered on a formal and frontal exploration, easily translatable into a statement and a photographic image that can circulate and be quickly and efficiently decoded.

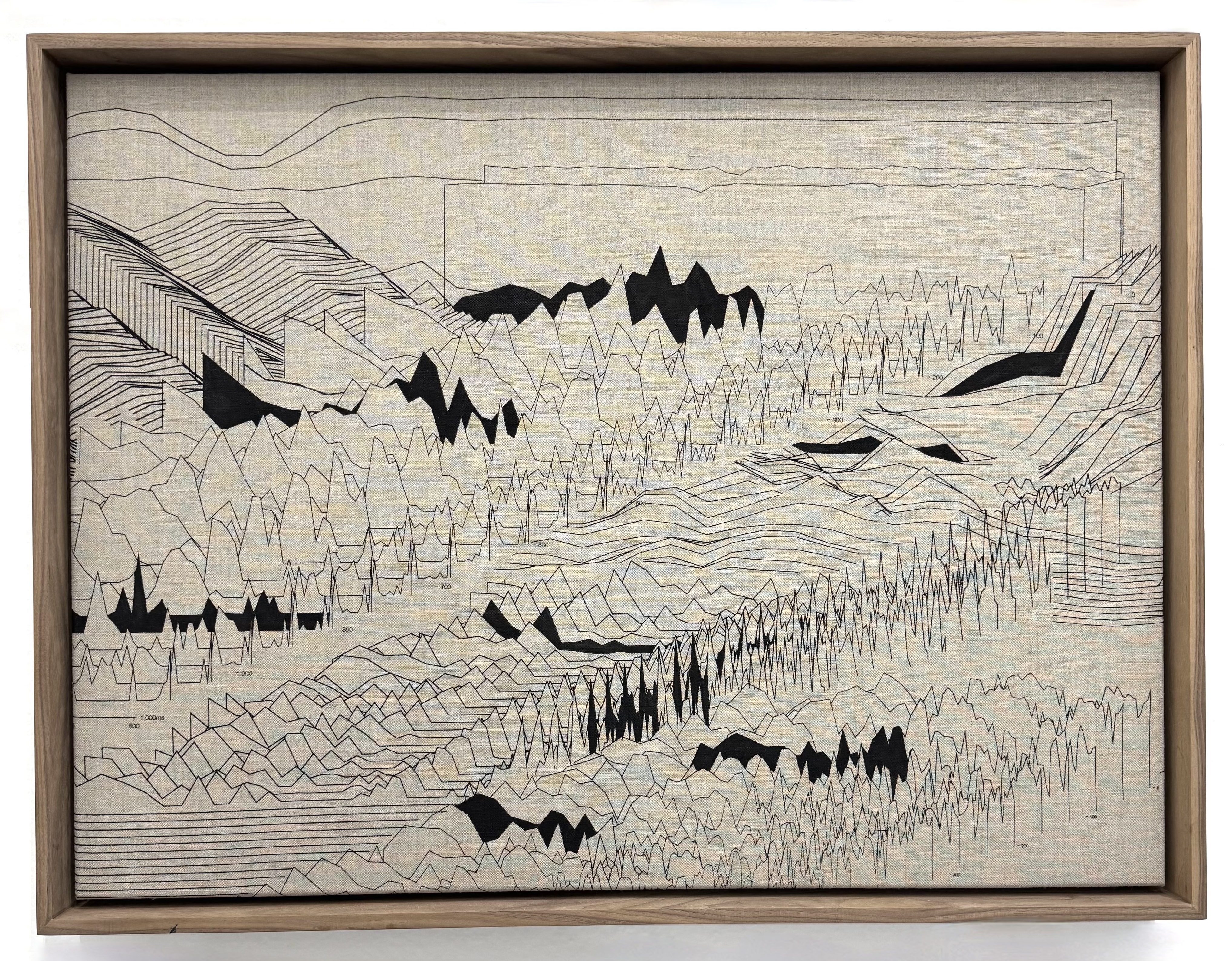

These forms can be divided into two broad categories: those that correlate with a conceptual or narrative investigation, such as AméricaLatinaII by Carlos Vielma, who, using brick dust, cement, and spray on earth, reflects "on the way architecture operates to uphold the modern ideology of order and progress that was instituted in Latin America during the last century;" and others that stem from relational or vital practices, like Toponimia: Zapopan I by Ana Paula Santana, where the frontal nature is interrupted when viewers touch certain parts of the landscape surface and hear a word.

I believe that this two-dimensionality, this marked frontality and form, is due to the very spatiality of Estudio Acme (which has a grid-like resonance with the 19th-century Parisian salons). It would be worth examining more carefully, case by case, whether this symptom is solely due to the logic of the Estudio, or whether it reflects a trend that permeates other productions and spaces as a consequence of the circulation of artworks as image and statement that align with a global agenda (however ghostly that may be). On the other hand, thinking of forms no longer as abstraction and figuration, but as derived from practices or concepts (there can also be an in-between), makes more sense in light of the current mode of attention and production in our artistic practices. I hope, in the near future, to further develop these aesthetic categories in more detail and with more space.⁴

Clarification Note

On October 14th, Salón Acme shared the following clarification with Onda MX: “Regarding the selection of the pieces that made up this first edition, the final curation was carried out by the founding team and Ana Castella, the general director. For the ten pieces that made up ‘Patios,’ recommendations from the Artistic Council were considered, while for the ‘Gran Salón,’ it was through an invitation to 84 artists, curated by the Salón ACME team.”

We appreciate their transparency regarding the process.

I’d like to add that during the guided tour they offered me on Sunday, October 29th, the information was different: that the Artistic Council had curated the exhibition, which might have been a communication error. In the press release, the information about who curated “El Gran Salón” is not clear, which is why I sought clarification that day on-site.

The argument about not having public parameters for the selection of works still holds, even with Estudio Acme's clarification. As I mentioned earlier, quoting Boris Groys, curation has as its condition of possibility the public circulation of the criteria with which the pieces are selected, communicated, and displayed. On the other hand, I also continue to emphasize the relevance of Estudio Acme in showcasing the work of local artists who have worked and exhibited both at Salón Acme and in various venues throughout the country during the fair’s existence.

I would like to stress that this is not a negative or positive judgment on Estudio Acme. For years, I have positioned myself against moral criticism; rather, it is about being able to engage in dialogue about the complexities of our artistic ecosystem, which concern all of us.

1: Boris Groys. “Politics of Installation”, e-flux journal #2 — January 2009. P.8. found in http://worker01.e-flux.com/pdf/article_31.pdf

2: Found in: https://muac.unam.mx/exposicion/yo-se-que-tu-padre…

3: Found in: https://material-fair.com/platform/estacion-material-vol-3/

4: Found in the Estudio Acme Catalog of Works: “Toponimia (2024) is a series of two-dimensional landscape pieces composed of acoustic analyses of the voices of inhabitants from various municipalities. The pieces are interactive, created using screen printing with conductive ink on a frame, and prepared with small speakers placed behind. In addition to exploring the onomastics of each region—primarily municipalities whose names derive from Nahuatl—these pieces suggest that the soundscape is also made up of the voices of its community. For this, I visit the municipalities and ask people to say the name of the place where they live, creating a collection of voices that I later analyze through FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) graphics to obtain frequency and amplitude over time.”

Published on Oct 13 2024