Interview

Mirage in the dark. On "Actos de Ilusión" by Fabiola Torres-Alzaga

by Nicolás García Barraza

In MUAC’s Sala10

Reading time

5 min

It’s common for me to find myself staring blankly, thinking about what could have been and about what I shouldn’t have done. I wonder if things really happened as they did, or if my memory has so thickened them that it’s hard for me to separate the flowers from the weeds. What comes to mind is something that’s been repeated to me on several occasions: “There are always two versions of the same story,” or perhaps three, four, five… It’s impossible to enumerate.

I was in the midst of gloomy reflections about what was true and what was invented when the video Actos de Ilusión (Acts of Illusion), by Fabiola Torres-Alzaga, finally loaded. I had a call with the artist scheduled on Friday, and I had spent a few days researching her work: the visual record of Entre Actos, an installation shown at the Museo del Chopo in 2014, as well as her drawings of a scene from Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad (1961). I felt like the man in that film, confused between the real and the imaginary, between what is one’s own and what is other than oneself.

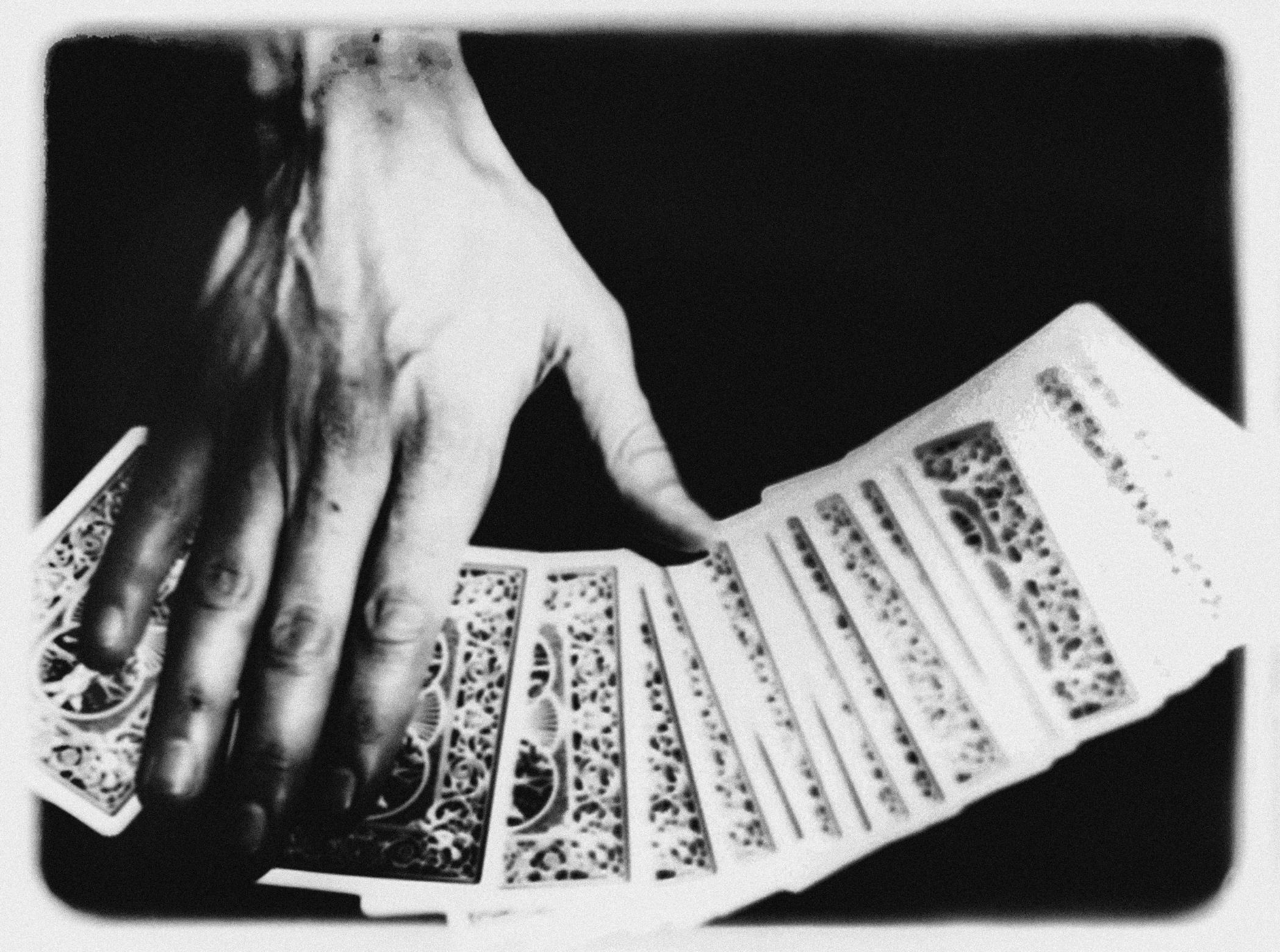

In the audiovisual presentation being shown in MUAC’s Sala10, Torres-Alzaga continues with the interest in the magical and the illusory characteristic of her work. The piece questions the viewer’s gaze—what it encounters and what it decides to ignore. On this occasion, she uses the theatricality of magic and of film in order to explore the ambiguity of perception, of what remains hidden, waiting to be discovered. In her words: “What interests me is that deception, perception, and point of view are components determining what is real.” This work reminds us that everything is in constant change, that nothing is static, absolute, or permanent—that we are movement.

What do we choose to look at, and how? What part of it really stays in our memory? These are two questions I ask myself while watching the video.

In Actos de Ilusión, the artist places us inside a theater—a forum?—though it might as well be a cinema. The deception takes place from the start, in the play of light and shadow, in the relationship between sound and silence. Everything plays an essential role in introducing us to a moment loaded with uncertainty and expectation. All of a sudden, a phrase shows itself fluctuating in my retina, remaining there even when the words have changed: “Lend your attention, and dim the rest out” (“Prestar tu atención y oscurecer el resto”).

(There are children laughing near where I am, I don’t see them, but I hear them.)

Shortly after greeting one another, we begin talking about how film has influenced our ways of relating to the world. Fabiola says that her work has often been influenced by cinematic illusions. She has a particular interest in the possibilities of misleading and of challenging the viewer’s perception: “It’s a matter of peeking out and modifying certain rigorous modes of reality. Every time there’s a different fragment or frame, we’re leaving out 360 degrees, turning our backs on another reality.”

With Actos de Ilusión one has to maintain an active gaze, and to consider the moment in which we determine what’s true and what’s not. The audiovisual work’s aim is to accentuate spaces of darkness through the persistence on the retina of those traces that remain when the image disappears, of the micromemories that create in the viewer the possibility of projecting an image.

We also discussed what film does and how it affects our minds. The first thing I thought of when Fabiola mentioned Lucrecia Martel was the latter’s film The Headless Woman (La Mujer Sin Cabeza, 2008). I recalled moments in which the action is taking place outside the frame, or in which the conversation we most emphatically listen to is not the one taking place in front of us. The artist’s work also invites the viewer to expand the frame of reality so that they might notice the creases lying behind them, realizing that one illusion hides behind another. In this connection Torres-Alzaga says: “Giving the possibility of existence to another reality, without trying to understand it or to negotiate with it but rather to recognize it, would be another way of getting away from the stereotype or expectation of what we seek or what we want to see.”

This idea reminded me of Le Tir, a series of landscapes by Nico Munuera in which he cut out the original canvas in order to present a small portion of the painting. It seems to me that it’s within editing and framing that perspective is transformed and the way we observe is brought into question. The series seems to be an unfinished story, much like Martel’s films or the magic tricks we see in Actos de Ilusión.

(I hear a truck announcing the sale of water jugs. I’m reminded of when we laughed at communal announcements.)

Finally, regarding magic, Fabiola says that it seems more complicated than it is, that it’s something that can be seen, without seeking it. Upon listening to the interview a few days later, I thought about how we are shaping our memory, safeguarding the fragments that best represent the way in which we learned to live and feel. “To free us from the expectations of what is in front of us”: I continue thinking about those words.

At the end we talked about other things that ended up in the audio transcription: some of those things immediately got away from us, some are those you are reading right here, others perhaps remained in the artist’s mind, different from those that remain in mine.

(I understood that what we have in front of us is a minimal part of the multiple possibilities.)

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on February 11 2021