Interview

That Curatorial Maelstrom: A Conversation with Tania Ragasol

by Carolina Magis Weinberg

Reading time

9 min

In Tania Ragasol’s most recent curatorial work, the table plays a central role as a place of gathering and commonality. The table is a space of shared potential, always awaiting what is yet to happen. A table holds possibility. I met with Tania at a table to talk, opening up the curational universe through conversation.

We began our dialogue; I wanted to get to know her, so I asked her to tell me about her life. Tania has dedicated many years to curatorial work, experiencing its many diverse facets. She explained that being a curator involves constant self-demand, driven by a need to be and feel useful, to be capable of everything, to keep doing, doing, and doing—to execute and solve. It’s a way of life filled with joy but also pressure and exhaustion. Our conversation evolved into various life experiences as Tania tried to encompass the complexity of her practice. Suddenly, a specific term arose that synthesized everything: she lives immersed in a “curatorial maelstrom.” The words reverberated heavily as I wrote them down; they carry a particular weight. That is the key: to curate is to be caught in an impetuous maelstrom, a centripetal vortex, an unbridled passion, a clustering of events. Curating is choosing to stay inside the storm.

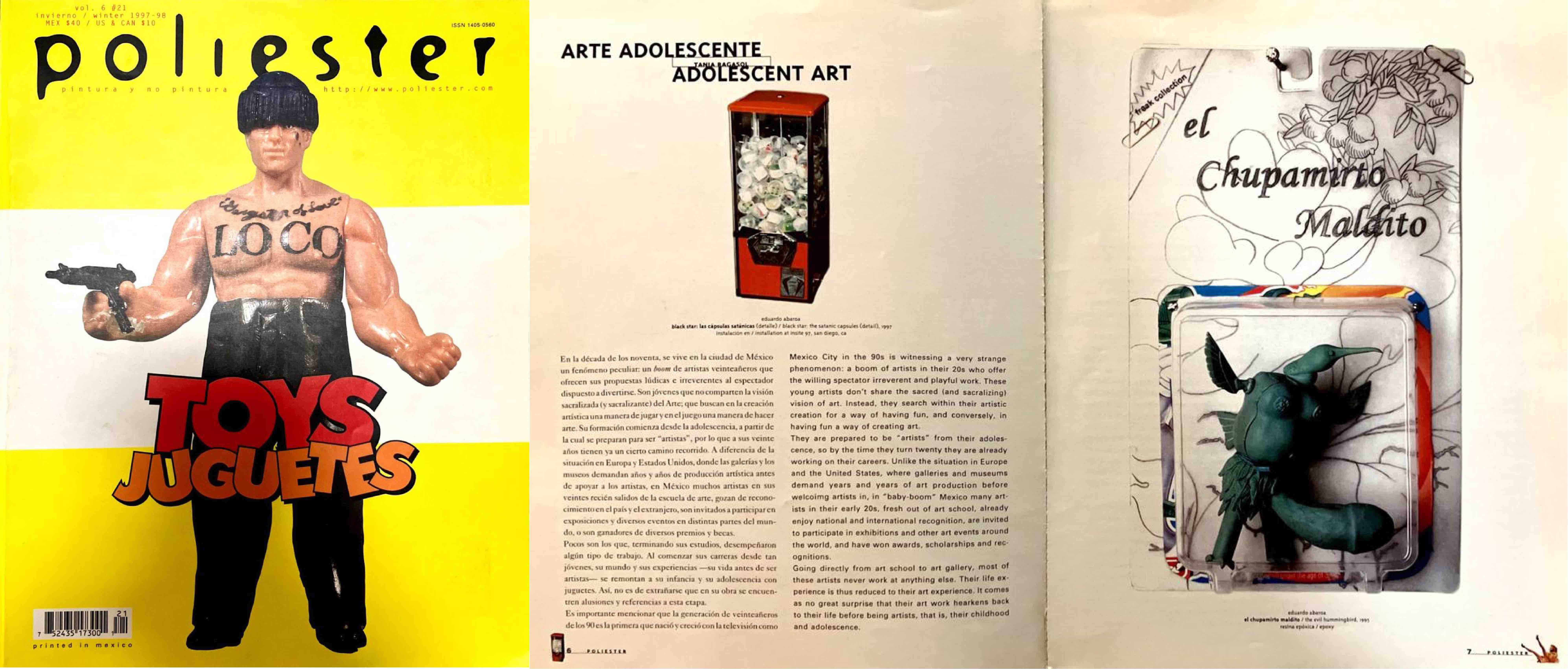

Tania described how she has experienced this maelstrom firsthand, from different angles. She shared how, early in her career, she witnessed the defense of the Edificio Balmori in 1990, experiencing firsthand what art can achieve. She recalled the power of the moment when Carla Rippey’s photograph was hung upside down at Balmori—a charged image full of political effervescence, representing a historical moment where art managed to stop destruction. A situation where art was both protest and celebration. We also talked about how, in those 1990s, she began connecting with the artistic scene, working as a coordinator for the magazine Poliester, pintura y no pintura, and how diving into the editorial process was almost like conducting an orchestra. She then mentioned the challenges of her curatorial profession, where she has worked with various public and private institutions and independent projects at different times and scales throughout her career: Museo Carrillo Gil, Museo Tamayo, Museo de Arte Moderno, Zona Maco, Casa Vecina, InSite_05, Cobertizo. Each space had its own dynamic, along with specific challenges and possibilities.

To survive the curatorial maelstrom, one must also work collectively. Since 2020, she has been part of Oficina Particular, along with Roberto Velázquez and Gabriela Correa. It is a professional cooperative of contemporary art advisors. Tania describes it as a collective that forms and dissolves as opportunities arise, working for the mission that each project demands, where each person shares their specific knowledge. A special project was Curaduría de Guerrilla, in which Sebastián Romo also participated, a series of exhibitions in the window of a store in the San Miguel Chapultepec neighborhood. The main characteristic of the project was curating for a space that didn’t require entering; it was visible from the outside, bringing contemporary art conversations to the street. They invited other curators to join: Marisol Argüelles, Violeta Celis, and Paola Eguiluz, who in turn brought new voices into the dialogue. Tania’s face lit up as she described this project as the first time the team owned every aspect of the maelstrom, a constant, intense, and above all, collaborative juggling act.

These accumulated experiences have led her to a current moment she recognizes as different, post-pandemic, where the forced pause allowed her to slow down the curatorial machine. A maelstrom that reignited in 2024 after her curatorial proposal for the Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was selected. Thus, amid comings and goings at different rhythms, she began considering the need to explore her own history as an archive, including her family history and the trace of her own journey in the field of curating.

When describing the practice itself and trying to pinpoint the essence of curatorial work, Tania delves into the need to pause in the face of the endless maelstrom and form alliances. She explains that being a curator is a very different job from being an artist: the artist goes into battle, the curator stays on the other side of the trench. However, it’s clear that in reality, they walk together because curatorial practice is necessarily a creative endeavor. In this dialogue with the external, a bond forms between the artist and the curator, a complicity born from affection.

Tania highlights a special curatorial adventure as evidence of the power that alliances and care generate in artistic projects. In November 2020, she traveled to León, Guanajuato, to discover a novel project: Trámite. Buró de Coleccionistas. Started in 2017² by Bianca Peregrina and Miguel Loyola in Querétaro, this project aims to build audiences and new networks in the specific context of the Bajío. As she told me the details, Tania smiled; the energy reminded her of the most exciting moments at the beginning of her curatorial career, something of that 1990s effervescence combined with immense joy and complicity. This project faces the significant challenge of activating a community and trying to create a local scene outside of Mexico’s power centers. In Tania’s eyes, this young project is full of desire for openness and a future-oriented vision. She has had the fortune to accompany it, noting how they’ve spent many years shaping this dream and have managed to build a rhythm that allows them to grow and sustain themselves. She considers it a success to have invited very diverse curatorial profiles, always with the openness and generosity to listen to all voices.

.jpeg?alt=media&token=bcecbfd6-ccef-4511-984a-fe09c5f6012a)

Tania continues her narration, noting that curating is a work of articulation, even describing it specifically as a work of translation. Just as with the word “maelstrom,” I hear the word “translation,” and I immediately pause to take note. This is another dense, weighty term that anchors our conversation. Translation is a maelstrom, positioning oneself in the complexity of two worlds, accompanying the transit of an idea from one port to another. A movement that also requires deep complicity.

It’s important here to underscore what translation as a craft entails. For writer Natalia Ginzburg¹ translation is an act of service. The translator uses the same tool as the writer—the word—but for a different function. Thus, that work “between meticulousness and fever” makes translation mean having to learn a new language every time. In curating, each project also involves speaking a different language; it’s about finding a common language between artist and curator.

Ginzburg describes a subtle duality: “To translate means to cling to and grasp each word and scrutinize its meaning. To follow step by step and faithfully the structure and articulation of sentences. To be like insects on a leaf and like ants on a path. But at the same time to keep one’s eyes lifted to take in the whole landscape, as from the top of a hill. To move very slowly, but also very quickly, because in such slowness there is and must be the urge to traverse the path at great speed.” Curating is then that silent maelstrom where one must move both very fast and very slow at the same time, seeing both a single leaf and the whole landscape.

Tania has spent a long time expanding her translator-curatorial role in both written and spoken word, seeking new forms and spaces. The podcast is one of them, a sonic space that opens up the visual, as in Visor, a contemporary art history program on the Convoynetwork platform. In it, she seeks to tell the story of art from the particular perspective of those who lived it. With this tool, she weaves personal memories with the recent history of art in Mexico to recount the artistic scene from the 1990s to the present. The idea is to plant questions and allow connections to form through words, linking the personal and professional as inseparable experiences. The podcast, which is also a publication, has created bridges to listen to the experiences of people like Karen Cordero, Rocío Mirelles, and Guillermo Santamarina. History is also that little history in lowercase.

We finally approach the vortex of the conversation. We talk about the project for the Mexican Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale in 2024: Nos marchábamos, regresábamos siempre by artist Erick Meyenberg. This curatorial adventure is also the synthesis of the alliances, affections, and acts of translation that have characterized her work. Tania highlights that the process began with a very particular curatorial situation, as it had to address the overarching theme established beforehand by Adriano Pedrosa for the Central Pavilion: Strangers Everywhere. In this sense, her role as translator was especially important since, on the one hand, she had to participate in the open call from INBAL and the Ministry of Culture with a pre-set theme; while, on the other hand, she had to build a partnership with the artistic vision of Erick Meyenberg’s personal project. Tania emphasizes how she navigated the maelstrom in deep complicity with Roberto Velázquez and Gabriela Correa, in a collective artistic and curatorial thought process that centered on using the space as a whole. It was crucial to think about translating Meyenberg’s piece into the specific context of the national pavilion.

And so, the curatorial maelstrom in which Tania Ragasol is immersed continues to amplify, grow, and twist. This is how we can hear a life and a specific way of doing that curious and specific translator’s work that is curating, while countless more turns in the maelstrom are sought. We rose from the table, still talking about a thousand more projects. We say goodbye, however, the conversation is only just beginning.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

1: Natalia Ginzburg, Translator’s note in Madame Bovary, May 1983.

2: The next edition will take place from October 10th to 20th, 2024.

Cover picture: TOMO 007, 2023. Courtesy of Trámite Buró de Coleccionistas

Published on September 14 2024