Essay

Inverted Effect of a Faulty Mirror: "Otrxs Mundxs"

by Verana Codina

At Museo Rufino Tamayo

Reading time

5 min

Otrxs mundxs (“Other Worlds”)—which opened to the public at the end of November and closed in mid-December due to our return to the much-dreaded color red in the traffic light marking pandemic life in Mexico—was the last show of the year at Museo Rufino Tamayo, but for many visitors it was the first one, after months in which so-called “non-essential activities” were prohibited in the city.

Its opening gave me an enthusiasm comparable to that of finally returning to watching a movie in the theater or of going to a live music gig after months of forced confinement.

Excited, I entered the museum. I approached the first gallery, read the title, and then the curatorial text. I sensed a generality in this statement, something that carried over to the title. “Otres mundes?” I thought.*1 I strolled through the galleries with some suspicion, waiting for a stance that would justify the use of non-binary language. At the end of the long tour—the exhibition consists of works by more than forty artists—my suspicion was confirmed: the ‘x’ is nothing more than a leitmotiv.

Also, the thematic nuclei dividing up the exhibition are handled superficially. The gallery text lists certain terms, but doesn’t delve into any of their implications, nor how words like capitalism, obliteration, or visualization are related to the pieces constituting these nuclei.

When the museum says things like, “highlighting otherness” or “[…] an institutional response [...] anticipating a post-pandemic alterity [...] not as a radical idea but as an achievable reality,”*2 I wonder: Since when have museums backed these voices of “otherness”? And even if they do—it’s to the benefit of what, or whom?

It would be delusional to think that those voices are genuinely being escorted by an entity like the Tamayo, as it would also be to discount the fact that certain works indeed contain or are traversed by what the curatorial text calls “urgent discourses.” In addition, we cannot ignore that the pieces’ exhibition is favorable to the career development of the invited artists.

It’s very clear—so clear that the curation begins from this point—that the vast majority of the artists making up the exhibition—even considering their privileges for having been included in an institutional show—represent the voices of a generation characterized by a constant challenging of models perpetrated to the hegemonic benefit of capital. A generation of “snowflakes”—so-denominated by boomers—whose fragility of opinion translates into incessant questions about how, into what or whom, and from where, we configure ourselves socially, culturally, politically, emotionally, bodily, and identitarily.

That said, by placing together established artists with emerging artists—or, rather, with less established ones—Otrxs mundxs aims to benefit those whose artistic careers are still taking off, introducing them to those who have already landed. For me, though, it seems to be the other way around: including less established artists and their works leads to urgent discussions that could renew the panorama of Mexico City’s artistic community. Arranging them in the same space causes the inverted effect of a faulty mirror, in which the “big ones” are reflected in the “small ones”—and not vice versa, as usually happens.

So, what do these other worlds say to us? Are they shared worlds? What does a piece by ASMA share with one by Guillermo Santamarina? Or Nuestra Victoria by Julieta Gil share with Paños by Tercerunquinto?

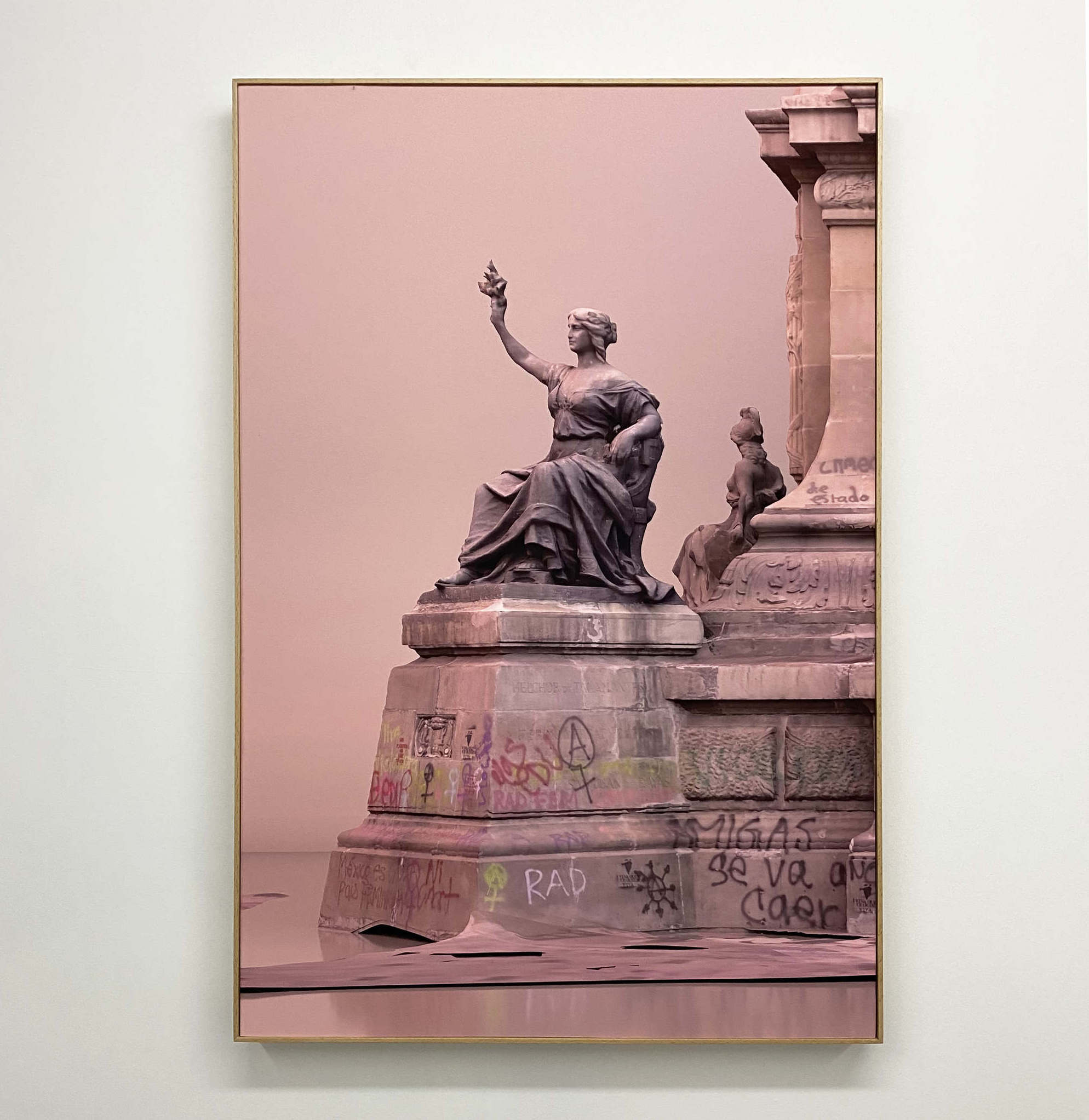

It will be thought that the correspondence between the latter two is obvious: both seem to want to rescue the DNA of a political event displayed in the graffiti left on monuments or in public spaces. However, whereas Tercerunquinto removes the paint—in order to turn it into a pictorial record— Julieta makes a photographic record: she leaves it there.

Recently, in a context of feminist demonstrations and marches, there have been debates about the use of public spaces and the role of monuments. Is their purpose to exist in order to be “vandalized”? What happens when these painted slogans are cleaned off? What does it mean to keep them, legibly, in their original place? Or even to make a record of them before they are removed?

Although the two proposals on hand seem either to ask or answer these same questions, the generational significance of placing Nuestra Victoria against Paños is indisputable. I think of the many times I would pass by the Angel of Independence when it was covered with barriers and wooden planks; knowing that these slogans existed, even when they could not be seen, bolstered a collective sense of resistance, fueled by the constant attempt by the city government to make them invisible. In this sense, removing them from public space—as Tercerunquinto proposes—weakens that feeling.

Like Julieta, many of the artists in the show present worlds that they advocate for, in which they can visualize themselves—worlds of which they want us all to be a part. Physical or virtual worlds, in which a body’s physical disability would not have to be repaired; in which a charro*3 can be a figure of gender resistance; or even another world, in which a space’s architecture and design do not condition our bodies.

Due to the city’s return to “code red,” the museum remains closed until further notice. Therefore, we invite you to enter here in order to learn more about the artists, who have made videos in which they talk about their work.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: Translator’s note: “Otrxs mundxs” and “Otres mundes” are gender-neutral ways of expressing the otherwise masculine “Otros mundos” (“Other worlds”).

*2: https://www.museotamayo.org/otrxs-mundxs-cedulario

*3: Translator’s note: a charro is a traditional Mexican horseman, typically from Mexico’s northern states.

Cover picture: Asma, Multijuice potion, Iron chain, stainless steel, white micro-paraffin, resin. Courtesy of the artists and PEANA gallery

Published on January 14 2021