Review

Do Bootleg Commodities Dream of Contemporary Art? On the ‘Recurseo’ of Jimena Chávez Delion

by M.S. Yániz

Reading time

4 min

It’s striking how colors and shapes seduce us. For ages, objects with their alluring and delirious surfaces have moved bodies—from the countryside to the city and, within the city, through its labyrinths and passages. With colonial modernity, the world became filled with a variety of objects from across the globe, along with the many techniques used to make them. Visual and material diversity grew beyond measure.

Entering Aferrarse a los márgenes [Clinging to the Margins] by Jimena Chávez Delion at the Enrique Guerrero Gallery means allowing yourself to be seduced by the commodity-form in its purest appearance: sheer surface without use-value. The exhibition abstracts a practice of informal trade in Peru. Recurseo refers to an additional activity, generally outside of regular work, done to earn extra income, to “make ends meet.” Though recurseo can be used to describe any informal work, Chávez Delion focuses on a group of women—mostly Venezuelan migrants—whose job is to paint the soles of counterfeit luxury brand shoes. These women work at the Centro Comercial Perú al Futuro in Caquetá (Lima), a controversial market dealing in contraband.

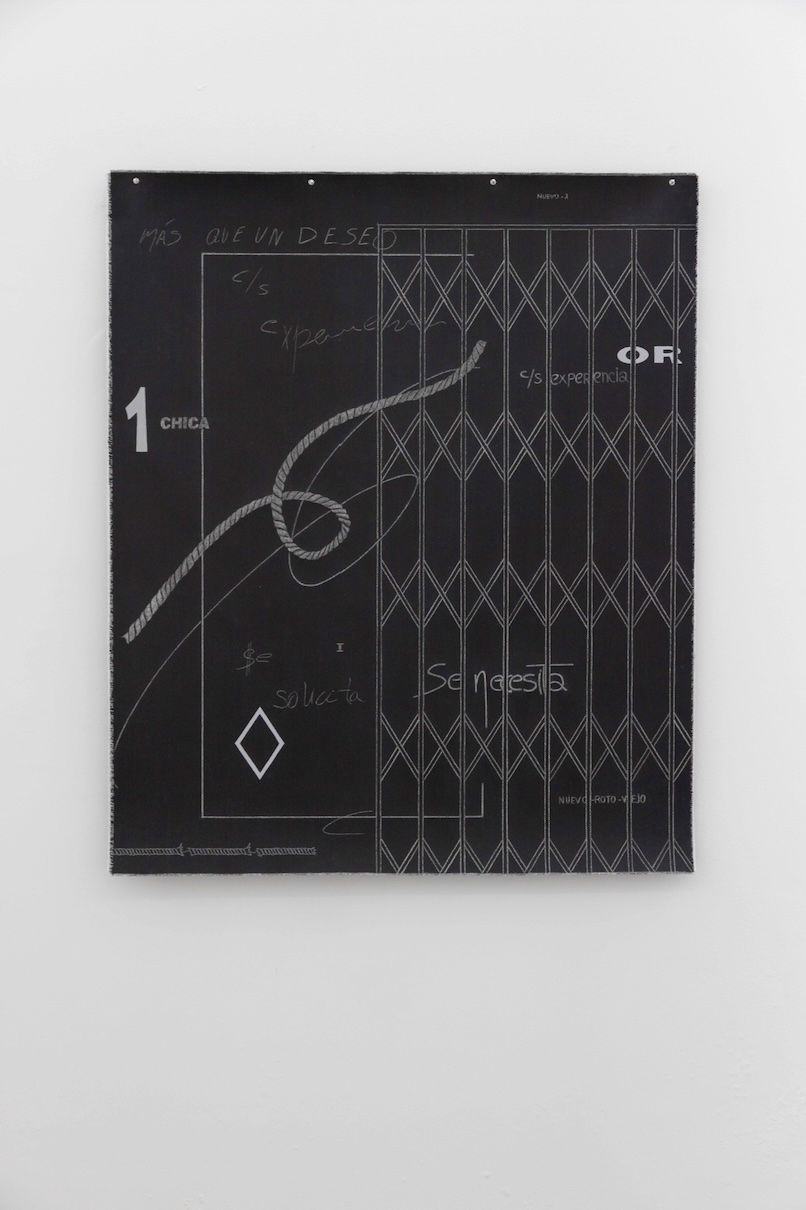

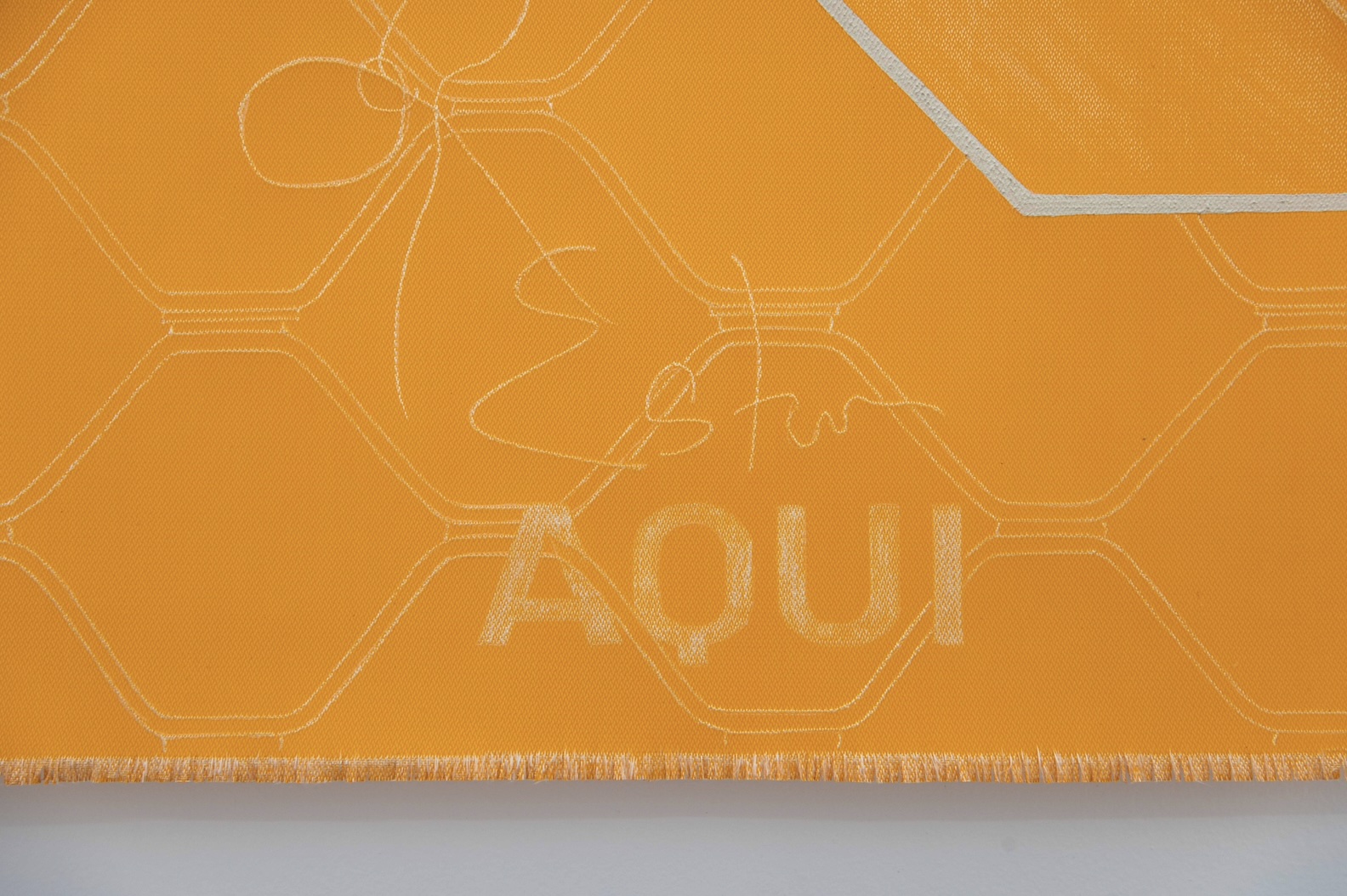

The women develop impressive technical skills to make the counterfeits pass: they hand-paint the soles, becoming experts in strokes that, when taken out of the sole's grooves, can be read as typical of modern painting. The series Encontrar mi pulso (2023) [Finding my Pulse] is, at first glance, modern abstract painting. However, within the broader body of work, it becomes a commentary on mechanical labor and how repetition under capitalism produces beauty.

The deliberate repetition of a movement for a specific purpose produces a technique, and over time, with accumulated series put into circulation, this in turn produces a style. In other words, repetitive labor creates an aesthetic. Charles Chaplin’s Modern Times shows how the body, alienated by manual labor, creates a senseless choreography that becomes independent of the product originally tied to those movements. Chaplin’s body no longer serves to tighten bolts, but it keeps performing the same actions. In this sense, the pieces in Aferrarse a los márgenes liberate the style from the products, presenting a discourse on the beauty of commodities rooted in the dreams of precarious workers.

Though critical of the piracy of goods, Jimena’s works exhibit a pristine formality. And perhaps that’s where the cruelty lies. The alignment of design with the capitalist mode of production makes it seem as though capitalism is the only possible modernity—so much so that counter-economies, or recurseo, are alienated by hegemonic forms. That’s the danger! The exhibition reveals that we are equally seduced by both artistic forms and commodity forms. We might ask ourselves if they are, in fact, equivalent.

The exhibition features nine series of works, some consisting of a single piece, others with multiple elements. All are abstractions or re-mediations of precarious manufacturing processes: a tower of unpainted soles, plastic scraps longing to be metal, an installation of shelves to display the soles, a video where the women workers talk about dreaming of their jobs, series of abstract paintings, and sketches with measurements and notes for carrying out the piracy.

Aferrarse a los márgenes by Jimena Chávez exposes how the economy operates monadically. Beyond the fact that GDP makes the national economy visible, at least in Latin America, monetary circulation follows sporadic and contingent paths, even in the corners that capital doesn’t see. An economy of the margins allows us to dream of being, for example, the center and the hegemonic power. The game is about clinging to a dream: being clear that through value production, one can—in the economic periphery—enter the circulation of luxury and absorb its surplus value. That’s where faith lies: in the belief that value is made up of circulating images, not so much the real, falsifiable things that can be endlessly pirated and re-purposed.

In the game of entering the circulation of the highest surplus value, the artist has outpaced the Peruvian economy, having recurseoed the recurseo itself within the grand machine of global surplus value production: contemporary art. If the informal economy generates value by copying luxury brands, pirate luxury within the art world can not only exceed the value of the brands but also enter into contact with eternity by canceling its use-value within the gallery and, if we keep dreaming, in the museum.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

Published on November 7 2024