Article

From the Intimate to the Social: Local Women Illustrators

by Sandra Sánchez

Reflection on the Work of Sofía Weidner

Reading time

6 min

When you’re reading a letter you’re so aware of the barest motivations to record and to communicate [… The letter] is a message that traverses a public system and arrives with a recipient. It travels over distance to get there. And the very, that very action, the very meaning of a letter, like, completely aside from the content of the letter, is to travel and to deliver [… The letters are] a desire for connection. (*1)

I watch MS Slavic 7, and I think of how the operation of the letter, described by Audrey Benac, the protagonist, bears certain family resemblances with the operation of illustration. Women illustrators also record and communicate, with words and/or drawings; likewise their messages go through a system (usually Instagram) and reach a recipient. Illustrations travel and deliver something in a desire for connection.

There’s another aspect that I think is shared by both illustration and correspondence: intimacy.

It’s important to show discretion, since just as we can’t put all of painting, or all of any artistic medium, in just one bag, neither can we do so with illustration. Thus, I should make clear that I’m thinking of very specific women illustrators, those in whom I find the intimacy of the letter (the illustrator’s proper name, her style, her urgency to communicate something) brought into play with an apparent paradox: the public space. I say apparent because in modernity the intimate and the public were constituted as separate spaces;(*2) the laundry is washed at home. Nevertheless, this boundary has been in dissolution along various fronts in the face of forms of violence wielded in private and which must be communicated, likewise in the face of the need to share, without shame, what happens to us in solitude.

Although in this text I will continue by speaking a little more about the work of Sofía Weidner, I think there are several other women illustrators (each with her own particularities) that depart from the intimate and the personal in order to produce and enter into a dialogue in the public agora. They speak about social, political, poetic, and recreational problems, using drawing and writing—illustration—as a means of expression. I am thinking, for example, of Mariana @marmarmaremoto, of Ange Cano @angecanomx, of Antonia González @tramoya, and of Amanda González @amandinalaandina, among others.

The aim of this text is not to pigeonhole these artists in a medium or to exhaust their work (which is ample and complex) in a few lines, but rather to highlight a quality, an operation that I find in their work: of starting from subjectivity (from a personal critical work) to point to the common.

Personally, to me their illustrations transmit a force derived from losing the fear of understanding oneself, far from heroics (that is, with all the gaps, the doubts, and the pains), in order to share impressions and social problems that are often structured by or are the consequence of a broader framework, one that includes the patriarchal violence of the state and its educational system, exercised on the bodies and psyche of its citizens.

Local art history and art criticism still have plenty of work ahead in order to understand and account for what goes on in illustration.

Sofía Weidner

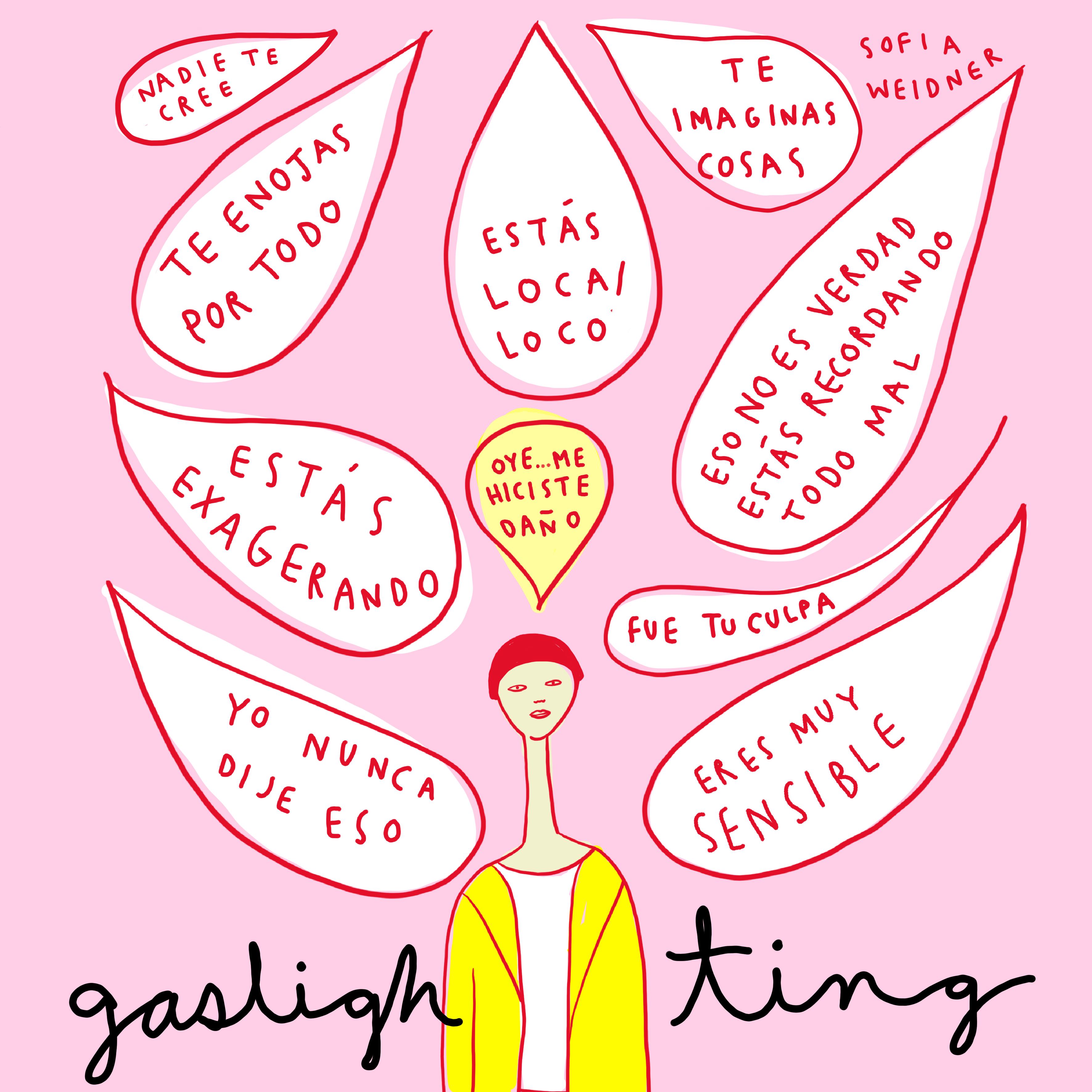

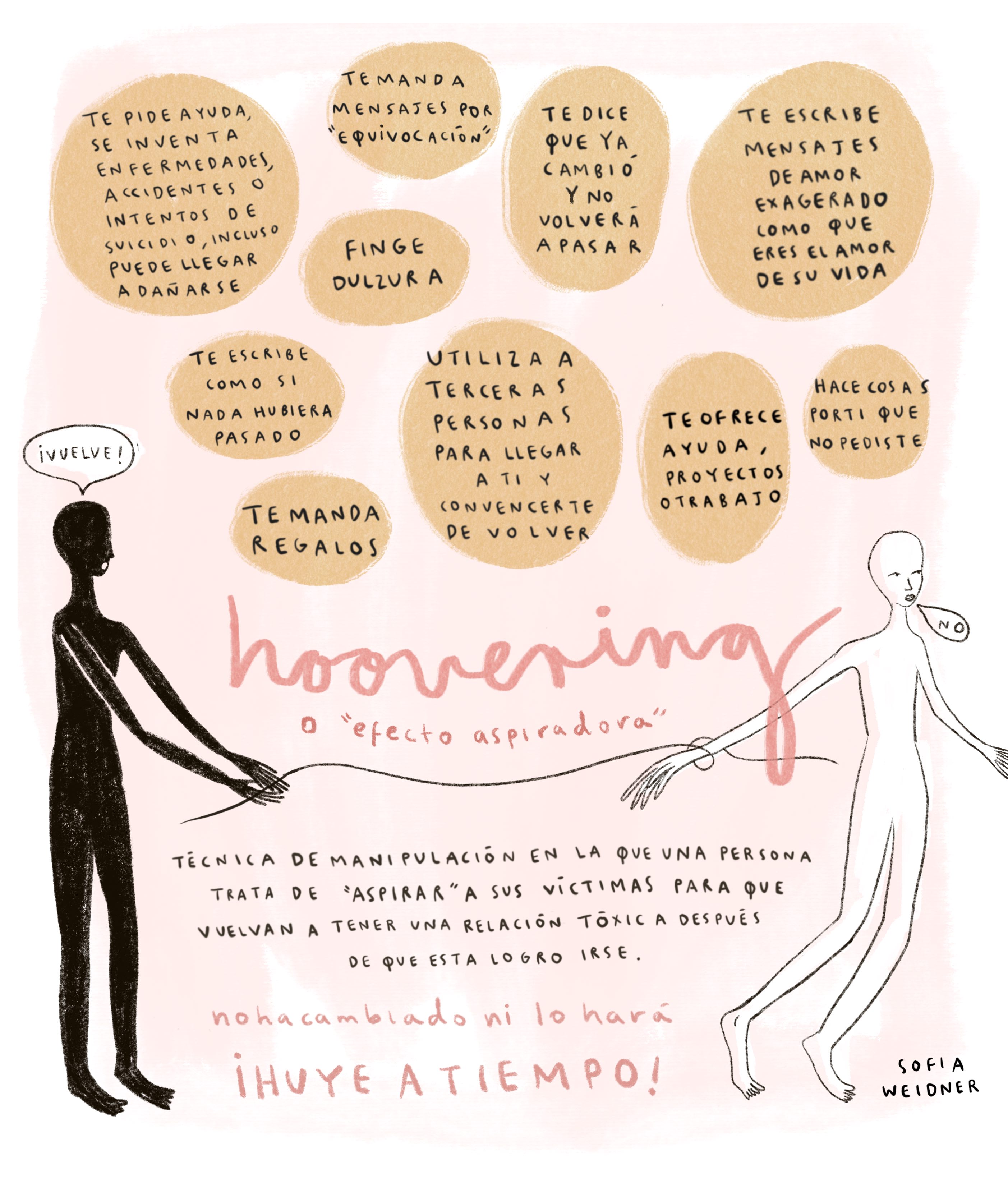

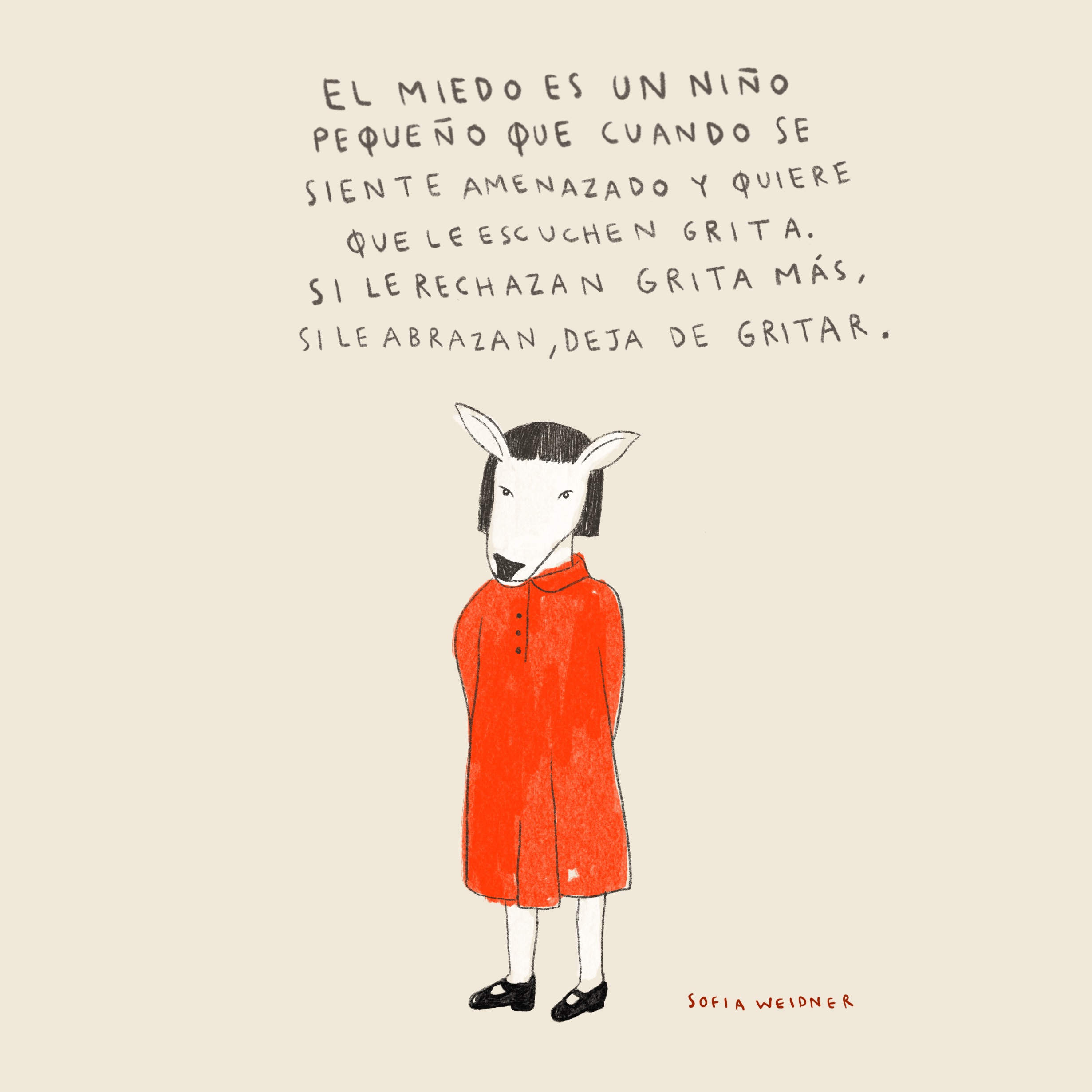

Sofía Weidner’s work touches on themes of mental health: fear is a small child who screams when he feels threatened and wants to be heard. The more they reject him, the more he screams, if they hug him, he stops, and feminist themes: in her illustrations she explains, for example, what “gaslighting” or “hoovering” consist in. Although her production does not reduce to one or the other, both are constant.

Her illustrations, digital as well as in other media, make use of the line in order to form the contours of shapes that may or may not contain color. They are generally accompanied by poetic texts or by information.

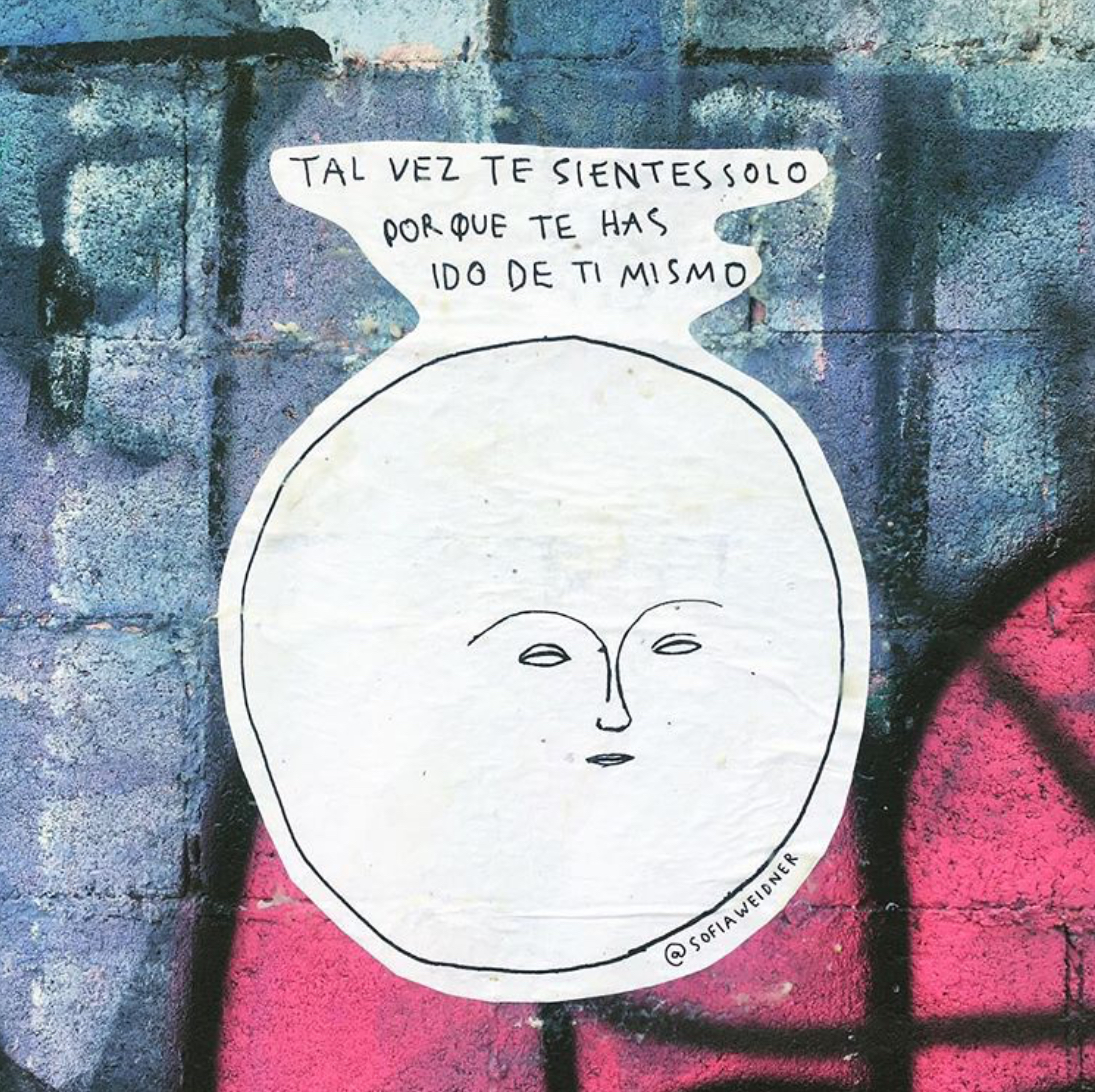

First I bring to the front a full moon drawn on a background of clouds with the following phrase at the top: MAYBE YOU FEEL ALONE BECAUSE YOU HAVE LEFT YOURSELF. I remember that the first time I saw this moon was not on Instagram (an important means for disseminating Sofía's art and that of other women illustrators), but on a poster put up on the wall of a street in Mexico City. It caught my attention because the message, appealing directly to the viewer, did not match the more typical playful, scribble tone found in prints and posters that artists put up on the street.

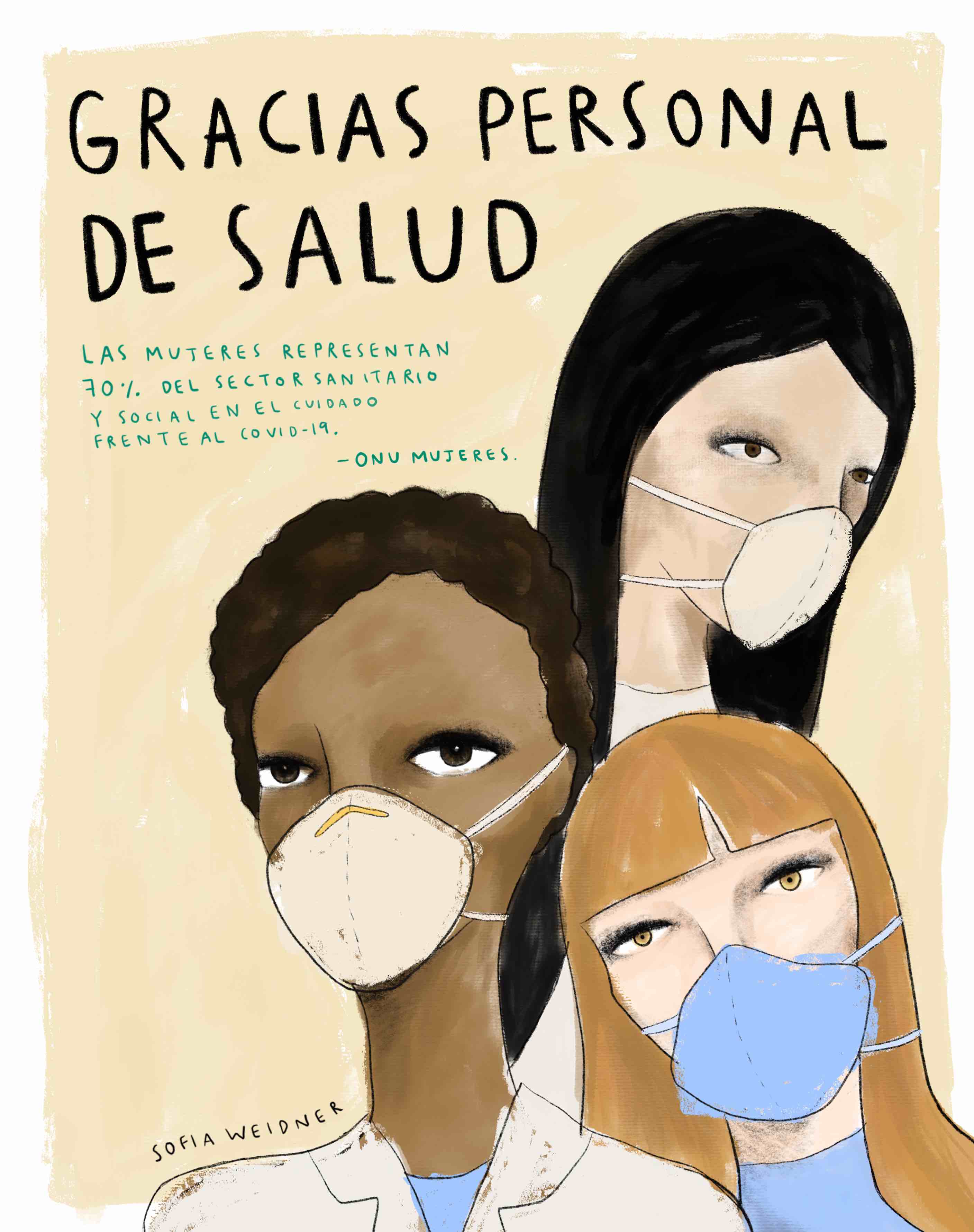

Second, and belonging to the current context, that of COVID-19, I highlight an illustration showing three women from the health and social sector wearing face masks. The image includes a statistic from the UN that says: “women represent 70% of the health and social sector in the care against COVID-19.” The merely informative function of such a simple datum is transformed by its accompanying the drawing, which shows particular subjects (not proper names or specific people) with singular gestures, movements, and countenances.

In her illustrations it is also common for someone, such as a woman or a cat, to interrogate us, sometimes humorously. On December 27, 2019 the artist published on her account the image of a cat asking us, LEFTOVER KIBBLES AGAIN?

As I mentioned earlier, I am interested in the artistic operation in Sofía’s work involving the transition from the intimate to the social. Her production communicates messages directly, offering an immediate dialogue. This quality is relevant because although it closes off the path to indeterminacy (valued in artistic terms, insofar as it allows for the viewer’s own interpretation to make an impression) it opens the path to conversation by working with themes that are relevant to the context.

*

No doubt, this very brief description is not intended to explain the artist’s work, but rather to acknowledge it and to bring it into a critical discussion. Sofía does not need this text; her illustrations are well-known. Rather, I, as an art writer, need to better understand her work and that of her colleagues: the mode in which they produce and in which they communicate with their public goes beyond the museum or gallery environment, putting at the forefront a mode of symbolic circulation that must be closely followed. Letters, perhaps? Maybe public letters.

*1: MS Slavic 7. Directed by Sofia Bohdanowicz and Deragh Campbell. Lisa Pictures, 2019. Starring Deragh Campbell, Aaron Danby, Elizabeth Rucker, Mariusz Sibiga.

The movie is available on MUBI

In a subjective shot, we see Audrey Benac (Deragh Campbell) sitting at a table, drinking a beer, narrating her thoughts after reading in the Harvard library the collection of letters that her great-grandmother, Zofia Bohdanowiczowa, had written to a poet friend.

*2: Kant himself separated out the logical, moral, and aesthetic realms.

Published on June 11 2020