Review

Castles: the Greigification of Architecture, Débora Delmar

by Verana Codina

At LLANO

Reading time

4 min

On the route from my house to the Metro there are approximately four buildings in which I would like to live. On the route from my work to the trolleybus there are two, and on the one from my house to my swimming lesson there are none. From my house to that of my best friend there are six, and from her house to the Oxxo there is only one.

My fixation on Mexico City’s architecture has led me to measure distances via a log in my cell phone notes, where I keep a record with brief descriptions of the places I like and their addresses. Simple entries such as “pink art deco house with planters, durango 348” are meant as reminders for a future point at which, if I run into them again, I can recognize them.

Observing details and learning to distinguish patterns from certain stylistic schools of modern architecture has led me to develop a certain affection for buildings and the neighborhoods they are part of. Undoubtedly, this obsession is fueled by the diversity of periods, styles, and typologies of home constructions that has housed the Mexican middle class for the last 70 years, and which has been made possible by the ever-changing nature of our capital.

The city’s mutability is caused by or corresponds to transformations that go beyond aesthetic interests, based on aspects related to the economy, market conditions, public policies, profitability, and land use.

Factors like these are increasingly moving away from the care that in the middle of the last century seemed to favor a building’s permanence through certain formal and aesthetic decisions regarding decoration, the finishing of details, the durability of materials, and the quality of the space—all today abandoned when prioritizing the immediate that is always related to a property’s rentability.

What data in reality account for the displacement of design elements like railings, planters, lattices, and staircases—built using such enduring materials as Venetian mosaics, granite, marble, and onyx—towards their total omission in recent years?

If I were to map my daily log, the addresses listed—whose buildings abound in decoration—would encompass neighborhoods concentrated in specific zones. The more centralized, the more surplus value, hence leading to the segregation of other, outlying neighborhoods. In this sense, architecture functions as a status symbol that reflects and accentuates class differences.

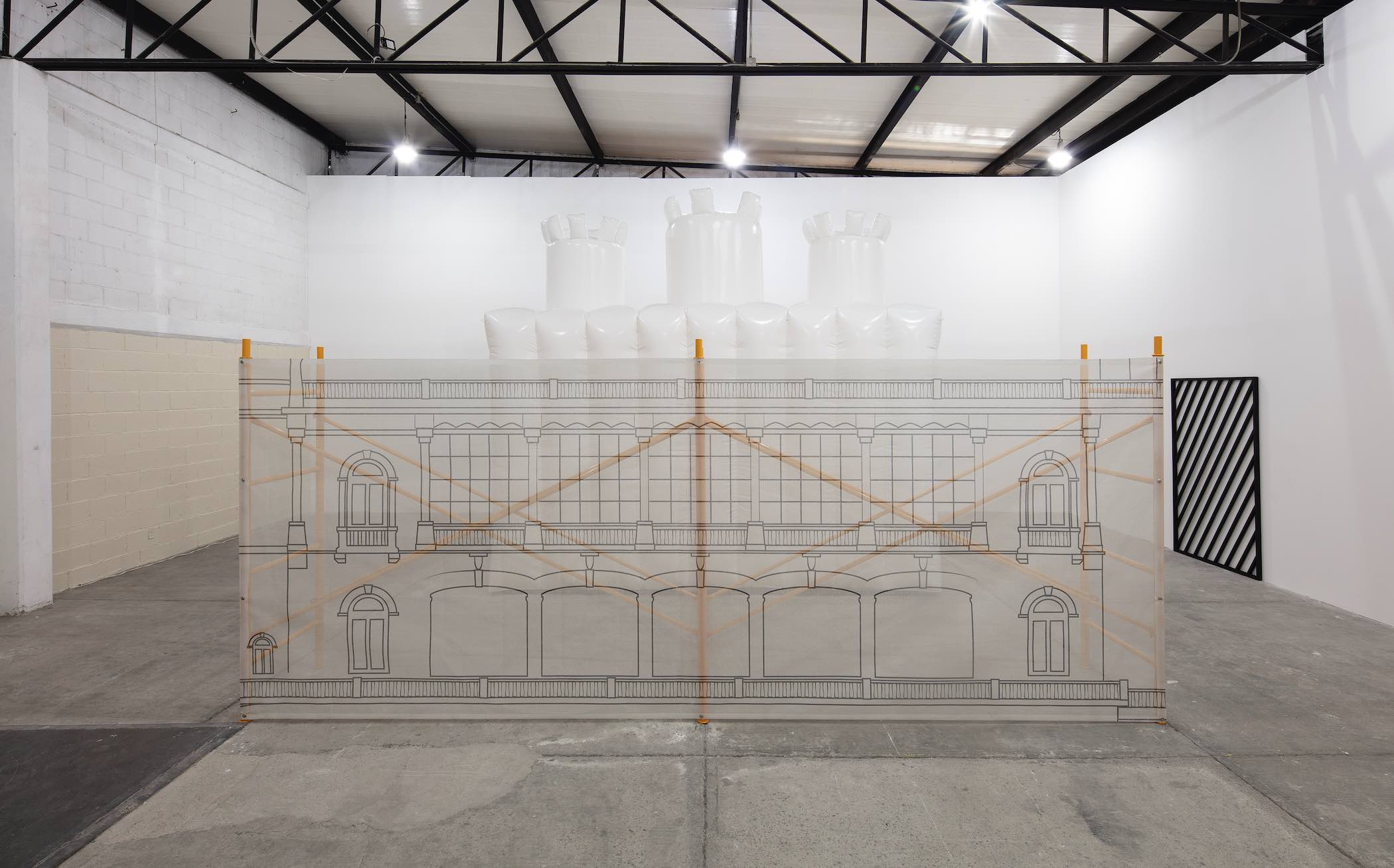

In Castles, her most recent solo exhibition, Débora Delmar arranges four large-format works that seem to circle around the latter idea. The set of pieces suggests a conversation about the domestic space, the architecture of the house, real estate values, and the social consequences that these set off. It is spread out in the gallery space, beginning with the construction of a false wall from which hangs a sign with a house number; a white inflatable balloon in the shape of a castle; four matte black metal railings; a yellow scaffolding covered by a mesh greige canvas, in a tone that is neither gray nor beige, illustrating the facade of the Chapultepec Castle; a keychain.

Débora takes symbols, whether everyday (a popular typology of a railing) or of power (the Chapultepec Castle) and by abstracting them she manages to bring current global problems to the table, such as the change in the urban landscape following processes of gentrification, evictions, and their strategies.

Little by little, interest in ornaments attached to the structures of buildings has been disappearing, replaced by solutions that neutralize the visuality of the design, “cleaning” and homogenizing its appearance. The phenomenon of “greigification” that the artist offers—by painting the walls of the room with that same tone—finishes off the idea that whitening and the inclination for order respond to an aspiration for a status that ends up fragmenting and dividing the social.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on February 12 2023