Review

Almost a Sign | About Roseta by Andrés Felipe Castaño

by Bruno Enciso

At Galería Karen Huber

Reading time

5 min

An image does not remain still. How could it? Even when someone seeks to set an image down in words, something escapes. Paul Valéry writes: “Just as water, gas, and electricity arrive in our homes from far away by an imperceptible maneuver, so in the future we will be supplied with visual images or organized series of sounds that appear and leave us with a small gesture, almost a sign.”

It amazes me that in an another epoch, Valéry writes about what is here, about us, about me. When the surprise subsides, I wonder about the author’s state of mind. With this intuition, how did Valéry feel? Afraid? Enthused? I do not think that the “small gestures” or the “imperceptible maneuvers” are neutral; if those images behave like water, gas, or electricity, they will be sure to cause dizziness.

That image was recovered by Walter Benjamin, who used it in his elaborations on technological reproducibility. He seems to have been very attentive to everything that happened after the emergence and expansion of photography and film. The world was out there and suddenly it’s here, framed. A tremendous shock! Not one of those shocks that provokes a scream, but rather one that shakes the eyes. Many things have changed; the frame was on paper, and now it’s also on screens. A question remains, however: Is the world that is framed here the same as the one out there? Benjamin suggests no, and up to this point I agree with him.

I thought of Benjamin when I had the pleasure of talking a bit with Andrés Felipe Castaño about Roseta, his show currently up at the Galería Karen Huber. I asked him how he made the decision to work with classical paintings, those that are studied in detail in art history books. He told me that one day he realized that all throughout his graduate studies—focused on painting—he looked at very few paintings; in fact he only looked at printed photographs. “And no two ever looked the same,” he said. Whether in this or that encyclopedia, from this or that publisher, paper, scale, ink, whether in old or new copies, none of them ever looked the same. Another tremendous shock.

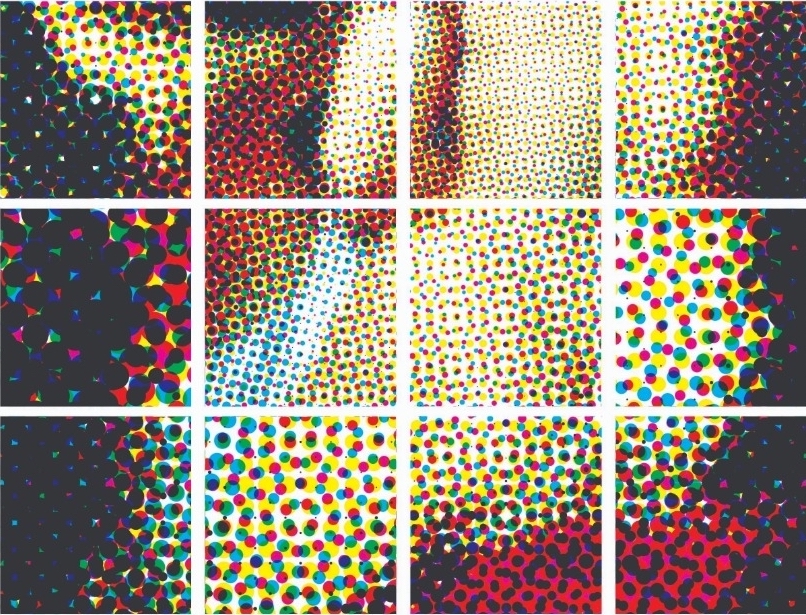

In Roseta, Andrés recovers the images of several classical paintings, and with them he rehearses a problem. He traces a grid over the paintings, and in each of their sections he assigns different degree of sharpness with respect to the original image. (One does not know where the original image resides.) It is as if the images arrived like water, filling bottles of different sizes and different degrees of transparency.

The selection of just eight images for the gallery works as a provocation to that current way of looking that needs images to be still and look the same. Picking a picture to look at is already to be attending to many images at once. I see it, and I turn to the myth it relates to me, to the classroom, to the music video it uses as a reference, to the text that describes the portrait of an era. I go to all those places without parking myself for too long.

I do not think that the work advocates for the importance of being in the presence of the authentic piece. In fact, I think that seeing the work on a screen suits it very well. Thus arises a question: What do I ask of an image in light of its frame?

The problem that the artist rehearses does not seek self-justification through concepts. The shock came to him when comparing different reproductions of the same painting in printed photographs; for that reason he decided to work with the materiality of the prints themselves.

The pictures are drawn by hand imitating an offset printing machine, the kind most used in the publishing industry. These are layers of regular and equidistant circles of solid colors that in their overlap constitute the image. Roseta is the technical name for this pattern. In the offset process the machine promises to be exact. In the pictures I find hands that, despite this insistence, sometimes tremble. And yet they do not lose any of their effectiveness in presenting the image.

Seeing the work and visiting the exhibition can release a subtle but violent shaking in our modes of seeing art, not just from the perspective of theories that analyze the supposed structures of an abstract subject, but also from the ocular exercise that anchors the apparent solidity of the artistic object: having it front of you. Roseta could very well unleash other writings that tackle everything from individual habits to institutional criteria of conservation and the use of classical works. If I think about the dizziness generated in me by these images, I also think about attending to them layer by layer, point by point. Sometimes I close my eyes.

*Benjamin cites Valéry in the third version of “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility.” See Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Volume 4 (Cambridge: Massachusetts, Harvard University Press), p. 252.

Published on October 9 2019