![Burying Your Feet in the Landscape [Enterrar los pies en el paisaje]](https://firebasestorage.googleapis.com/v0/b/prod-ondamx-art.appspot.com/o/media%2F1635424819852-sw.jpg?alt=media&token=42969651-b8f5-449a-a34b-3a509d99150c)

Review

Burying Your Feet in the Landscape [Enterrar los pies en el paisaje]

by Claudia Cisneros

Curated by Lorena Peña Brito at the Museo Cabañas

Reading time

6 min

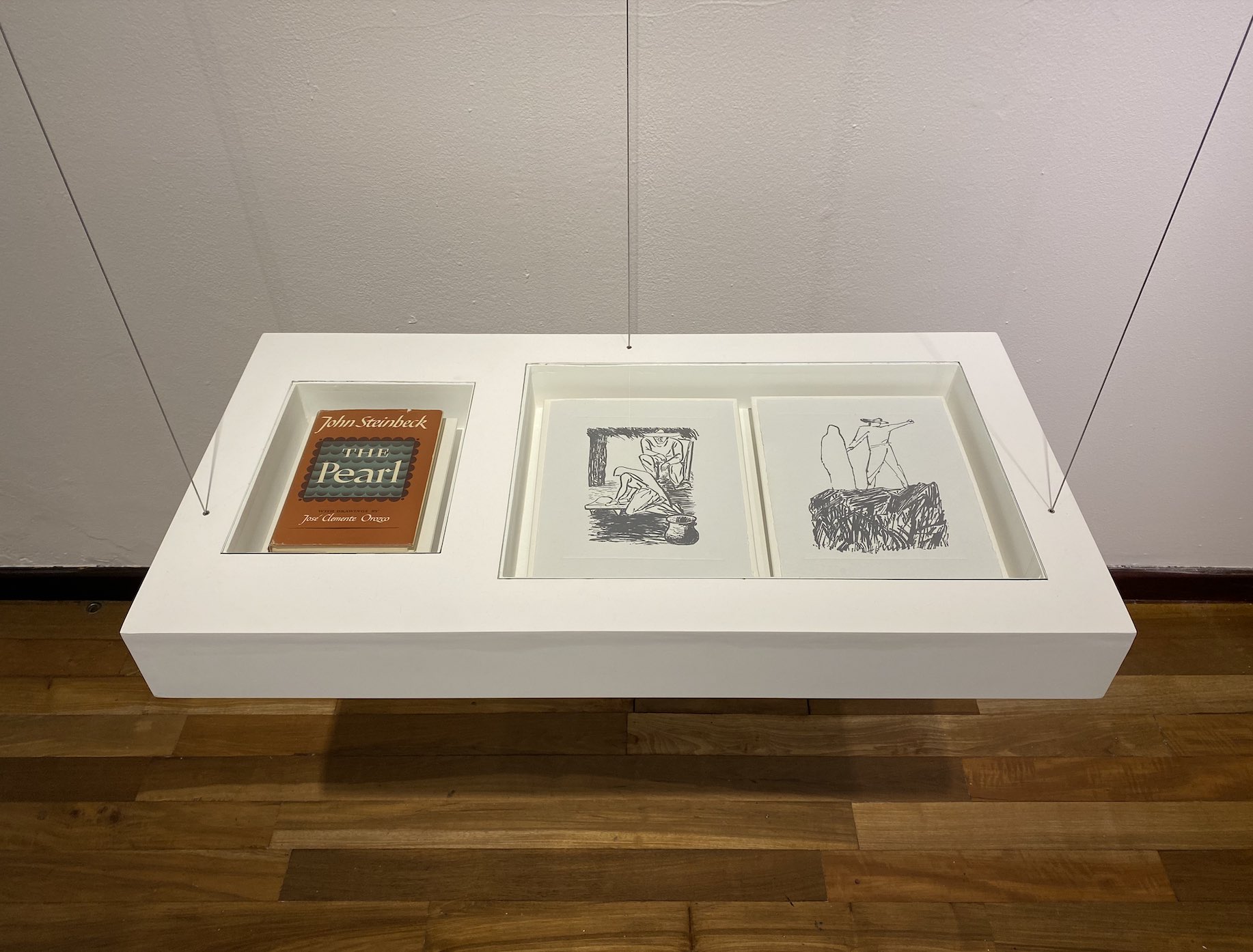

Burying Your Feet in the Landscape [Enterrar los pies en el paisaje] is the first collaboration between Museo Cabañas and the KADIST Foundation. The person in charge of bringing it to fruition is Lorena Peña Brito. While reviewing the Collection of Museo Cabañas, Lorena found two ink drawings by José Clemente Orozco, commissioned to illustrate the novel The Pearl by John Steinbeck, published in 1947. These illustrations were the starting point in selecting the pieces that make up the exhibition: three from the Acervo del Pueblo de Jalisco, three from the Gabriel Figueroa Archive, nine from local artists, as well as eleven videos and one photograph from the KADIST Collection. The project offers a dock with several mooring points for both collections.

The proposal has been designed with two parts, the one that has just been inaugurated and another that will open in January of next year, adding new pieces and modifying the existing organization.

For now we have contact with three voices that articulate certain conflicts: the one arising from the collaboration between Orozco and Steinbeck, the female voice inspired by “Juana,” protagonist of The Pearl, and the perspective of childhood—perhaps the one that is most complicated to address.

In addition to these voices, the selection revolves around the conflicts that the book raises, which continue to prevail up to the present moment: a story from the perspective of a foreign author—who was as close as possible to the social phenomena of Mexico’s coastal province at that time—as well as the exploitation of both labor and environment, and the violence brewed in areas of tourism and the exchange of goods.

The work giving shape to this exhibition is by the artists Raúl Anguiano, Ramiro Ávila, Guy Ben-Ner, Guillermo Chávez Vega, Elena Damiani, Edith Dekyndt, Gabriel Figueroa, Florencia Guillén, Kiyo Gutiérrez, Binelde Hyrcan, Karrabing Film Collective, Natalia Lasalle-Morillo, Charles Lim, José Clemente Orozco, Fernando Palomar, Thao Nguyen Phan, Daniela Ramírez, Enrique Ramírez, Alicia Smith, Sriwhana Spong, Chanell Stone, and Ana Vaz. And the pieces’ dates range from 1942 to 2020.

Lorena is a curator, writer, and cultural manager. And, although she has settled for many years in Guadalajara, “The Pearl of the West,” she grew up in San José del Cabo, Baja California Sur. This year, on her Instagram account, some of her photographic and video records showed the coast of San José in black and white. Later I learned that from there she “buried her feet in the landscape” [“enterró los pies en el paisaje”].

The three rooms making up the show are located around one of the patios of Museo Cabañas: for this reason, to go from one to another it is necessary to enter and leave, interspersing the outside sun with the darkness of the rooms. Different temperatures and densities. Water and sand.

In the first room one finds, on a floating base, a copy of Steinbeck’s book as well as two prints of José Clemente Orozco’s drawings. On the walls there are three stills from the film photographed by Gabriel Figueroa and two original drawings by Orozco. A small screen embedded in the wall reproduces a fragment titled “Crestomatía” [“Chrestomathy”], a term used merely to resolve the “fair use” rights of the piece, but that also suggests—in a curious way and and coming from other places—the curator’s pedagogical and management practice. This is the smallest, whitest, and brightest room: a pearl located in the landscape.

Upon entering the second room the light diminishes; a much larger and dimly lit space sends us back to an underwater ecosystem. The pieces living at its bottom appear on the walls.

A green pearl emerges from a tiny fold, discovered by a spot of light. A video of two hands holding a piece of paper underwater: the sun reveals saline movements on it, showing traces—drawings made without pencil. In the center of the room, a large chalupa: we don’t know if it’s moored or shipwrecked. On the walls, two paintings of beaches. A video and two photographs of women whose bodies frame a territory. One of them not only frames it, but reveals it to us, staking herself in the middle of a planting in some urban environment. She proclaims it as part of her body. Finally, a video and a bench for sitting and watching: the camera explores the landscape of an underground oil infrastructure and accompanies a man engaged in navigation. The sound of this piece, being the only one in the exhibition, enhances the environment, filling it with fluid dynamic resonances.

One has to cross the sunny patio with still-wet clothes in order to enter the third room, which is much smaller. Warm and soft light, like being on the seashore with your feet in the water.

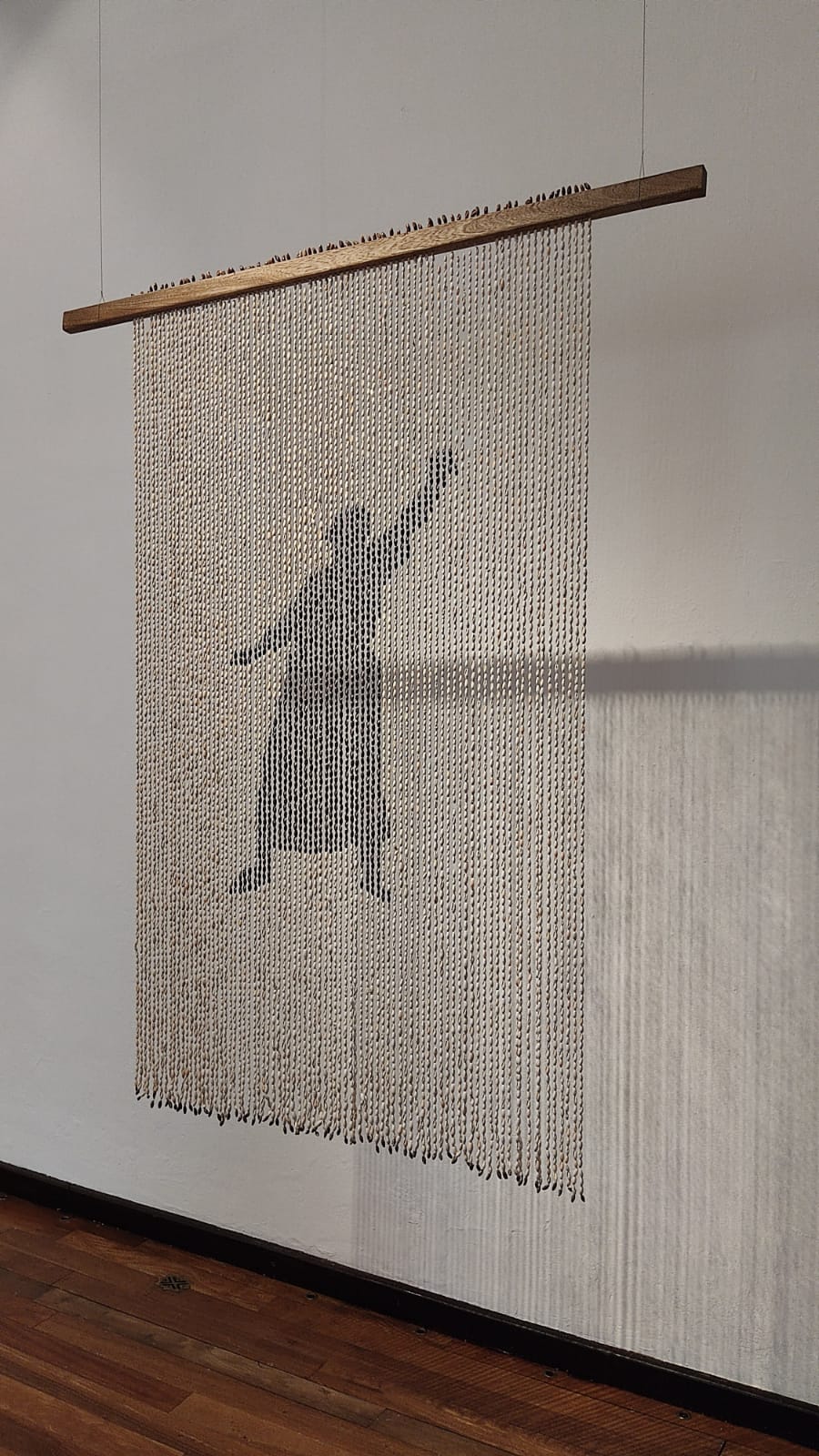

First, two paintings: one with a strelitzia and the other with a heliconia, black arrows marking movement patterns that correspond to salsa dance steps traced on the flowers. To the side: two hanging panels, one like a tapestry and the other like a bead curtain made with snails. At the back: a projection covering the entire wall. In it, four children sitting on holes they made in the sand simulate the organization of public transport. One of them drives the imaginary truck facing the sea, the passengers joking about their limitations and economic aspirations. This video, unlike others in the exhibition, is perceived as a record of something that takes places frequently and spontaneously.

One has to take one’s feet out of the water and walk via the patio again in order to enter the fourth and last room, which—it turns out—has no water: only sand and tropical heat.

At a certain point, between the waves and the nearest populace, we find a series of watercolors showing illustrations of a ghost town. On the right: a final two-channel projection in which a group of children sleep, play, and walk in what also feels like a ghost town. The little actors, with their uniforms, interpret the only book to which they have access in their community, inside a rural school and amidst beautiful natural landscapes.

The presence of the “child” in this exhibition’s pieces plays a connecting role, crucial to its docking at whomever observes them. In the child’s experience of union with nature, the author registers their own impossibility of bonding. We as spectators witness both. Every Sunday at 12 PM at the Cinema of Museo Cabañas two additional videos are screened. One of them: about the incautious indoctrination of a wild child.

Upon leaving the final room, after gaining a natural balance of densities, the body ends up calculating the pressure difference and, without remedy, digs its feet out of the landscape and walks away, in the direction opposite of seal level.

— Claudia Cisneros

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Cover picture: Sriwhana Spong, Beach Study (2012), video still. Courtesy of the artisdta and Kadist Foundation

Published on Oct 30 2021