Review

Brushing the Tender Edges with Your Fingertips: Javier Barrios at Pequod Co.

by Adriana Flores

Reading time

4 min

Long before the human species walked the Earth, our world was inhabited by cold-blooded creatures who lived within tenuous landscapes. The oceanic blue contrasted with a terrestrial sea of vegetation in shades of brown and green; there were plants, and yet no grass or flowers. It was not until the Cretaceous period that a shift in the landscape occurred; angiosperms, or flowering plants, then appeared. This species, whose reproductive organs are wrapped in deliciously colored petals, give off pleasant aromas in order to attract the presence of pollinating insects, not to mention the gaze of those who carefully contemplate the grace of subtlety.

I think of the first appearance of flowers as an almost fantastic event. What would have been the reaction of the first living beings that foolhardily approached them in order to absorb their aroma? How many bodies have we surrendered to their fleshy and velvety shapes, unable to avoid touching their tender edges with our fingertips?

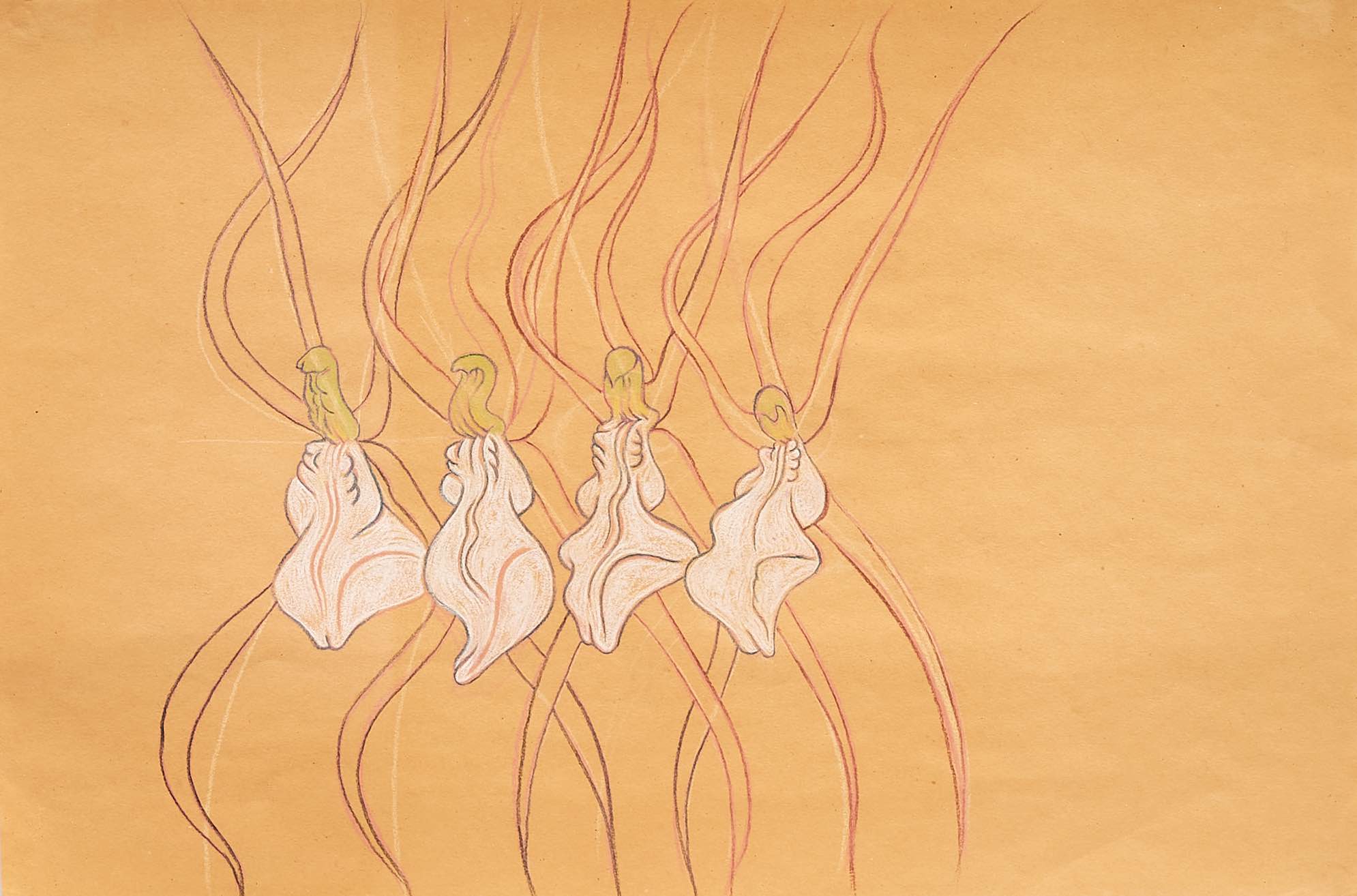

Javier Barrios inevitably succumbs to this enchantment, concentrating his fine pulse on drawings that capture one of his most exotic obsessions: orchids and other flowers as enigmatic and sensual characters. Casa de Sombras is the artist’s first solo show at the gallery Pequod Co., displaying a series of previously unexhibited pieces from between 2019 and 2022.

On display in one of the rooms is Buddhist Visions of Hell, a series of drawings that portray the conception of the underworld according to Eastern religious practice. According to his imaginary, orchids are deities that travel through the different levels of hell, taking control of this place that punishes the human species. “For this series I wanted to make strong/strange situations coexist with beautiful elements such as orchids, since it struck me that a religion like Buddhism, which is popular for its Zen vision of life, had at the same time a place like the underworld where they unleash different super-violent situations,” Barrios tells me while I observe in detail some severe faces among the petals.

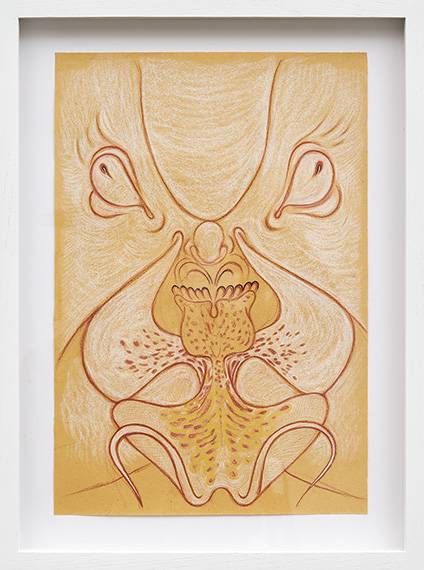

Aparición No. 3 is yet another stunning drawing owing to its inventive visual language, as the artist captures his symbolic imaginary by fusing iconographic elements of Mesoamerican and Asian culture. Barrios points out regarding this piece: “I have my ethical limits when it comes to taking elements from other cultures. Nevertheless, I like to create these images where I try to group different symbolic elements and make my own vocabulary in order to give meaning to these beings from my own mythology.”

In this drawing’s composition, two large flaming lotuses can be seen with a detail of pollen in the center that holds them together, while in the lower part we see shining jadeite incrusted in a jaw. These elements give life to a deity that has a double power: it is at once a destructive and a life-giving force thanks to the fire conceived from the aforementioned pre-Hispanic vision.

The same thing take place with Peonia de fuego, another of the drawings that can captivate us by virtue of its petals, similar to bursts of flames. I take stock that I have been absorbed in my own thoughts when Barrios’s distant voice invites me to continue the tour in the next room.

Suddenly, before my eyes stands an impeccable wooden construction that looks like a small shelter, lit from within. Javier explains to me that with this piece—rather than generate a political-historical discussion about what greenhouses and orchids represent colonially—he wants to explore possibilities close to scientific illustration and the sensation of walking through a botanical garden.

Invernadero is a sculpture installation that aims to be a work diary, bringing together the artist’s favorite orchid species. Each panel, drawn in watercolor, shows portraits of orchids that, within their vegetal condition, expressly warn of the irremediable event: they witness death for the first time. This piece’s fable-like plot concerns a moth about to be eaten by a bird. The grace of the subtlety at the mercy of death, the fatal rite of life.

My gaze follows each of the faces drawn on this piece’s orchids, and I think of Emily Dickinson’s poems, of those poets seduced by the emblem of the flower, not only as an object of admiration, but also because of its enigmatic nature as a system of ephemeral vitality. Meanwhile, Javier assures us as we end our visit: “The sensuality of flowers is an immanent characteristic; it is not necessary to add much more to them, since they already have enough eroticism in themselves.”

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on January 12 2023