Interview

Learning New Imaginations: An Interview with Christian Camacho.

by Bruno Enciso

Reading time

7 min

The expansion of the Monterrey art scene is not limited to its offerings of exhibitions, fairs, and other art events, but also includes new approaches to the training of young artists. On this occasion, I interviewed Christian Camacho—in his capacity as a teacher, rather than as a painter—in order to learn a little more about his experience and stance regarding current art school education.

BE: What would you say is the main difference between the artistic education you are offering and the one you received?

CC: I think about that all the time: about the mistakes made and the terrible things that happened in my school environment. The first thing, and this is something I’ve talked about with many people in my generation, is that I believe we had a violent school. There was an environment of anything goes, which meant that anything goes in doing anything to everyone. I don’t know if there was an area where we could get to work with the others without implying a strong lack of security. It was this vulnerability that would easily lead to abuse, violence, suspicion, and intrigue.

In the end, art is deeply personal and I feel that at that time nobody was explaining it that way; they rather insisted on approaching it from a unilaterally historical, cultural, or political point of view. I think we were rarely asking ourselves, “What happens to people who are given these possibilities?” I try to stay close to this question. I make sure that everyone in my class can put themselves in the shoes of the others, myself included.

What happened to us a lot was that it seemed that some teachers were only interested in the voices of certain types of people. I feel that this was unfair and that it displaced many types of imaginations that did not have to be displaced. Over the years to come, we saw some of those imaginations thrive despite that. I seek to make sure that such strict differentiation doesn’t take place in the classroom.

The other thing that’s important to me is talking about certain pieces and ways of making art on their own terms. I’m not interested in blocking things that seem aberrant or problematic to me. Rather, I try to show a new way of looking at them, without overlooking their place in more recent history. For me, teaching doesn’t work through echoes; understanding something doesn’t necessarily have to do with learning to replicate it. And neither is it a matter of originality, but rather one of ethics. A person who isn’t willing to see his or her work from various points of view, including those that take into account relationships with others, doesn’t have much to do with studying this.

I end up learning a lot from my students. I think I can say to them, “I have no idea what you’re talking about, but that doesn’t lead me not to care.” Or I can screw it up, screw it up a lot. To me it's super-potent to be able to admit a mistake or not to be afraid to say: “I don’t understand this well. I thought I did, but I think I still have room to understand it better.”

BE: How long have you been in Monterrey and what brought you there? Before you entered UDEM [the University of Monterrey], had you already taught classes within a bachelor’s level program?

CC: Now, in August, it will be two years since Lucía [Vidales] and I arrived, in order to join the UDEM teaching staff. There are many things I did in the past that were perhaps similar to this. Several times at the Museo Jumex, as part of the programming work, I offered training on mediation and accompanying the public. These were all themes related to art and it was a multi-month program. Even though not everyone who participated were artists, it included follow-ups and developments of projects.

Jumex shares with UDEM the spirit of a private organization, as well as new spaces and architectures, all designed to address art. The public museums and institutions are very different in their structures, processes, and traditions. In that sense, even though the groups were new, I didn’t feel as though it was such a crazy jump.

BE: What are some challenges that you have faced as a teacher in this city, one that is new to you? This is, of course, in addition to everything that involves making advances with distance learning.

CC: There are many, many things. The most important has been in renewing the way of teaching, not only when it comes to the syllabus, but also in working with students. I would feel that there were many deep-rooted ideas that kept everything fixed, limiting our openness to new practices. We wanted to encourage the renewal of interests and curiosities, with a basis in the materials and working methods themselves. The aim is that the student population remain interested in maintaining their artistic production after graduation.

It seemed to me that, although the students carried out many exercises, they often did not develop bodies of work or exhibition projects of their own interest, at least until very advanced stages of their careers. It was complex, because it was a question of concretizing processes of imagination. That was the first big challenge, and it had nothing to do with the pandemic.

Derived from this, it was necessary to promote self-criticism, self-management, and to see how the interests of each student developed, along with what took place in the classes. Now in the mode of distance learning, I believe that my greatest responsibility has been not to loose each other, the students and I. Not only to avoid their dropping out, but also so that they could maintain their curiosity even if the workspace was completely transformed. It was no longer so much about stimulating them to start new processes, but also about helping them to safeguard the involvement of each individual with their own training.

BE: How do you think your work as a teacher has affected your production as an artist?Perhaps formally, or something more related to your experiences.

CC: It might seem that because of my work I have less time to produce, but it also happens that many other things come out of the classes. I’m writing a lot, for example. In general, I think that teaching atomizes many of the skills you already had in order to be able to talk about something or simply in order to show it. I may not be filling the studio with works, but the progress hasn’t stopped either.

In addition to the question of time, the processes have changed. Now everything takes place at the table: the classes, the food, a lot of the production, and also some of the distractions. On campus it happened that I always imagined many new processes and materials. That impulse hasn’t disappeared, but it has gone elsewhere. It’s a favorable dispersion that maybe I can’t exactly explain.

It’s worth emphasizing how much I learn from my students. They’re doing things in ways that I don't manage, and with many references that aren’t mine. I’m interested in where I am when I can’t quite catch them. I surprise myself all the time; it’s crazy.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Recently, Christian Camacho curated the exhibition UNITS, by Jessica Wozny and Robert Janitz, for PEANA. Together with Lucía Vidales, he shares a selection of works by students through the Instagram account @pintorasdedomingo.

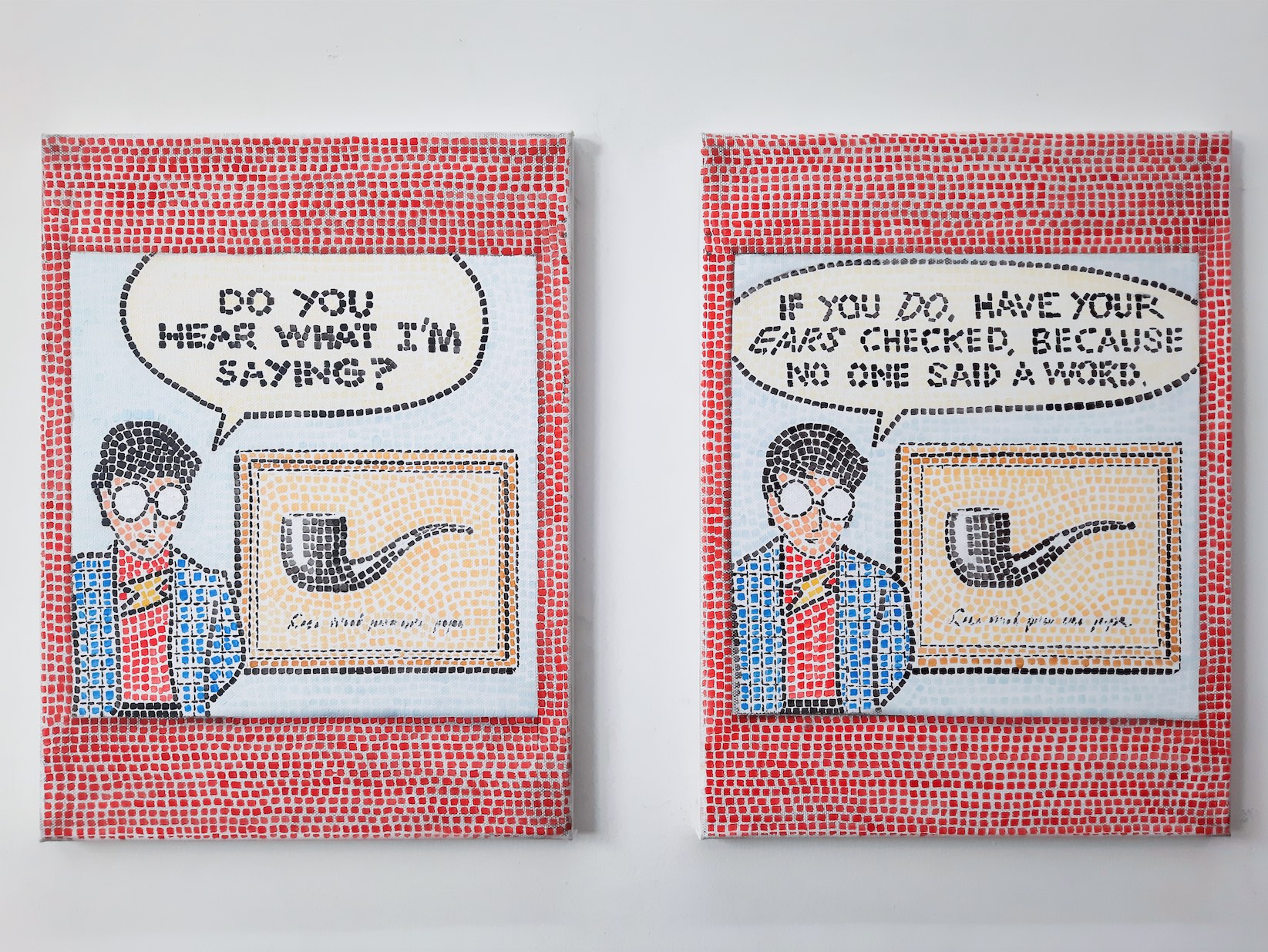

Cover picture: Christian Camacho, Do You Hear What I'm Saying?, 2020. Courtesy of the artist

Published on Jul 10 2021