Review

Learning to Nibble

by Stefanía Acevedo

About "Rat Attack" at SOMA

Reading time

8 min

With Rat Attack, eleven artists are presented as part of the end-of-course show for the SOMA Educational Program’s 2020 class. Each artist offers a different episode within the exhibition, in which some of the interrogations bringing them together include processes of object-production and their history, the transformation of landscapes, and the value of art itself. The class is made up of Perla Ramos, Ángela Ferrari, Clemente Castor, Israel Urmeer, Josué Mejía, Marek Wolfryd, Martin Bernstein, Oswaldo Aranda, Samuel Nicolle, Valentina Guerrero, and Wendy Cabrera Rubio.

Two emblematic representations constitute the show’s imaginary. The first is the figure of the Rat King, a group of rats held together by a knot of hardened filth that forms on their long tails. Although movement can become a problem, the rats learn to live linked together and to grow together. In that sense, the Rat King is constituted by the eleven artists and is distributed throughout the different spaces at SOMA. The gallery information sheet is laid out as if it were a labyrinth; consequently, viewers join in the nibbling experience. The individual artists’ questions and investigations are diverse; however, they find their point of union in the exhibition’s assembly, the distribution of the pieces, and the research exercise that operates as backdrop for the work.

Rat Attack also alludes to the arts-and-crafts TV show Art Attack and its motto: “You don’t need to be a great artist to be great at art.” In parodying this program, the artists question the figure of the expert and the supposed difference between expert and apprentice, as well as the distinction between arts and crafts. This is problematized from within the educational context framing the exhibition, in which a process of learning and exchange took place between tutors and students. Inevitably, questions emerge about how the teaching of art is imparted, and, more radically, about whether the creative act in artistic processes can be learned or taught.

As Urmeer shares with us, “The way we had experienced this type of education was in institutions that sometimes replicate this type of arts-and-crafts programs that we saw on TV, in which we learned to do things at home and that were based on the assumption that it would make you more creative. Art schools often do this. At SOMA it’s not like that.” This indicates the need for training spaces that continue to wager on processes of production that are closer to research and to conceptual reflection.

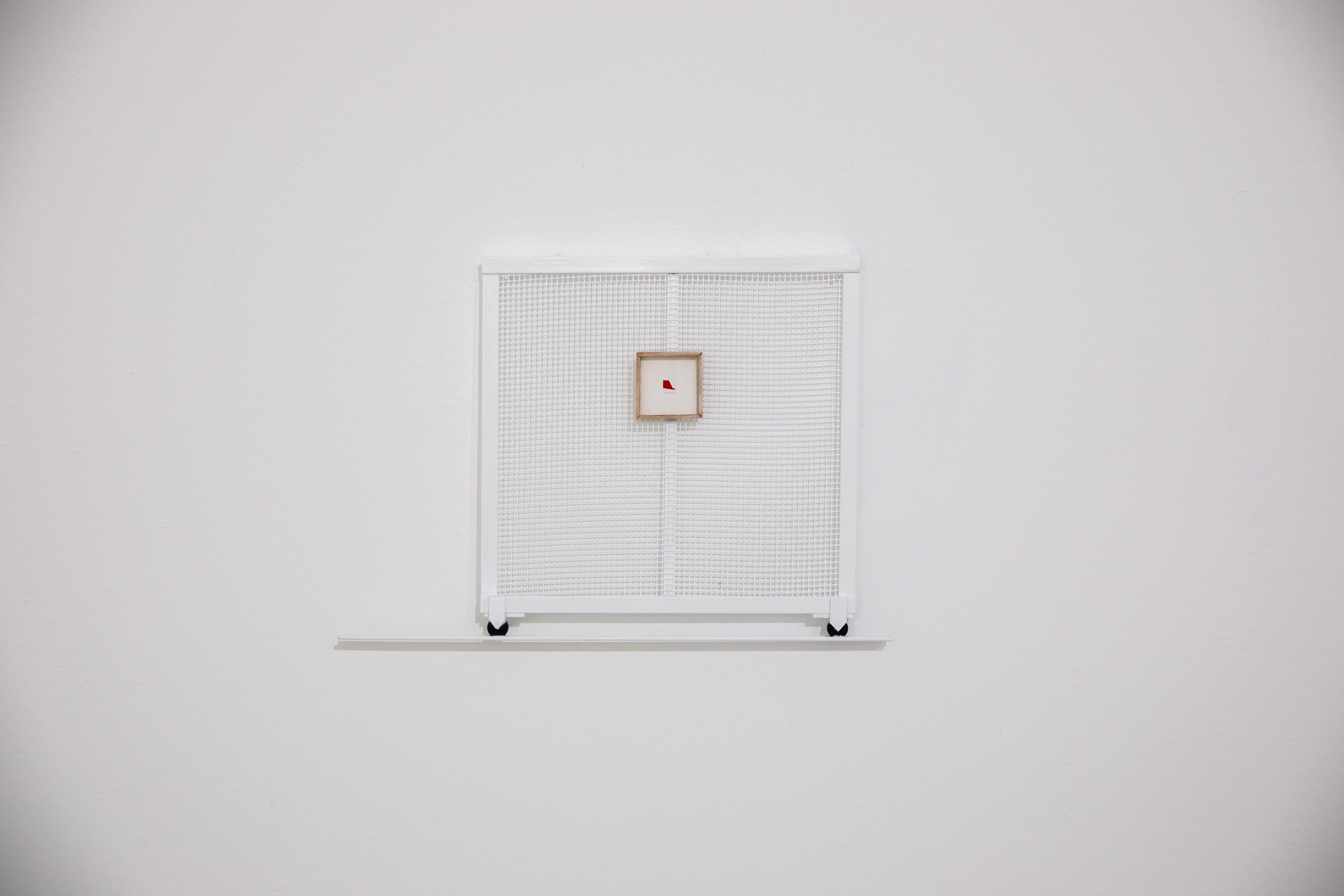

This reflection is accompanied by those discourses lining artistic practices and forming part of the system that positions certain works as objects of investment. In that sense, Porfolio de inversión #1 (Cuando todo lo demás falla la persistencia te demostrará el camino) [“Investment Portfolio #1 (When All Else Fails, Persistence Will Show You the Way)”], by Marek Wolfryd (Mexico, 1989), shows art objects as financial assets and brings into discussion the role of collecting and the commercial value of works of art.

In the stream of historical discourses about art, situated within political debates, one finds But tell me, Donald, have you ever been to Baia? by Wendy Cabrera Rubio (Mexico, 1993), who presents an installation in which artisanal puppets await the performance that will bring them back to life, back to 1978, in order to tour the First Latin American Biennial in São Paulo. The question about political history that runs throughout the pieces, made of felt, reflects Cabrera’s research on the context in which her own artistic production takes place, as well as her performative and didactic operations.

Specific attention to the production of objects begins with Esplendor de la industria automotriz mexicana en tiempos de amistad [“Splendor of the Mexican Auto Industry in Times of Friendship”] by Josué Mejía (Mexico, 1994). The artist has retraced a parallel process that took place in 1932: on the one hand, the creation of a mural that Diego Rivera started at the Detroit Institute of Arts, funded in large part by the Ford Motor Company; on the other hand, the correspondence between President Pascual Ortiz Rubio and Edsel Ford in order the finalize the opening of the first Ford plant in Mexico. Mejía explores the historical and symbolic relationships that sustain apparently disconnected objects.

Processes of production are also in question in Great - Warm - Impressively, a video-sculpture by Martin Bernstein (Argentina, 1986), composed of objects purchased on the Alibaba sales portal and intervened-on from China. On three walls are projected the videos that constituted the intervention made by Vicky Zou, a sales representative with whom the artist has stayed in touch. The question of capitalist production is part of Bernstein’s research on the systems of exploitation that we import and reproduce.

SSSS by Oswaldo Aranda (Mexico, 1988) presents an investigation into the lost objects that the artist collected during his work as a passenger security agent at the Chihuahua City International Airport. The archive narrates the story of his own search process, but also questions the spaces of artistic activity: that is, the very domains of art-making. The artist could be an ethnographer, but also a security agent.

Reflection on the object itself is charged to Samuel Nicolle (France, 1992), in whose work sculpture-objects have a leading place. In the installation Beaux dégats-tengo un cagadero en casa [“Beaux dégats-I’ve got a shithouse at home”], the artist shows us a group of seven sculptures that could give rise to a TV set. These sculpture-objects were conceived in a process of creating images that can take place on different material supports. This episode represents a turning point in the exhibition, one that opens the way to interrogations about the sensual aspect of objects and images.

Thoughts about the body and the erotic take place in the textile installation Un paisaje [“A Landscape”], by Ángela Ferrari (Argentina, 1990), which questions the border between the exterior and the interior using a large curtain that presents a hand-painted natural landscape. Ferrari’s work seeks to transmit the sensory experiences that occur within the body, even when they might be grotesque.

Primavera (acelerador de imágenes) [Spring (Image Accelerator)] by Clemente Castor (Mexico, 1994) shows us another kind of grand curtain with a post-apocalyptic landscape, where nature hides in its undergrowth the residues of what was once a civilization. The artist presents a video installation of a virtual reality in which an animated being speaks to us in a language that we still do not understand. In both pieces a transformation of the horizon takes place that transports the viewer to a gloomy interiority.

An iconic landscape is featured in ¡POPOOP! la montaña humeante [“POPOOP! The Smoking Mountain”]. This piece alludes to the pop culture that has fed the imaginary around the volcano Popocatépetl, a character that Urmeer explores through its registrations across different media. The artist presents us with an animation telling the story of the volcano’s visual representation in three moments: the calendar, Dr. Atl’s painting, and its continuous surveillance by a camera that records it in real time and transmits it over the internet.

Perla Ramos (Mexico, 1985), in #atlasdeletrasturísticas, reflects on the presence of iconic and capitalizable landscapes. This giant # refers us to a photographic project composed of an archive of monumental letters distributed across different geographies, which end up turning into a selfie. The installation, in being located in the patio, is affected by the weather and by the wear-and-tear caused by the rain and sun. Ramos also presents a selection of three photos that form part of the atlas and that are distributed throughout different spaces at SOMA.

In the patio one also finds A las plantas se les nombra por sus hojas [“Plants Are Named for Their Leaves”], a piece by Valentina Guerrero Marín (Chile, 1994). The artist observes that the definition of undergrowth (“maleza”) refers to a feminine name given to weeds and undesirable plants that grow wild. Starting out from the nomenclature, it presents an installation that consists, on the one hand, of a type of nettle called “mala mujer” (“bad woman”), planted in SOMA’s courtyard, accompanied by a commemorative plaque describing it; and on the other hand, of a room in which we can enter, walk around, and generate the cracks that fragment a white cement floor covering a foam ground. This piece invokes an unnatural landscape that has placed femininity as that which grows uncontrollably, but acquires its transgressive power in being implacable.

Rat Attack is accompanied by a microsite where one finds various materials that delve into the creative process behind the pieces. It is also complemented by “Miércoles de SOMA” [“SOMA Wednesdays”], a virtual program airing at 8:30 PM on YouTube. All together, the virtual resources make explicit that this class does not need exuberant or expensive materials in order to sustain their practice; on the contrary, they have made it into a process of reflection whose primary value lies in accounting for their own formative development. Although each artist works individually, it should not be forgotten that in the art system they form part of a great Rat King in which they must learn to live linked together and to grow together.

The exhibition will be open until October 17; schedule your appointment in advance.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on September 26 2020