Review

Andrea Martínez: The Folds of the Landscape

by Carolina Magis Weinberg

Reading time

4 min

There’s a silent explosion in the gallery Lateral: what comes out of it is not the disorder of chaos but rather parallel lines, precise folds, and the order of meticulous observation. We are in the black and white world of Andrea Martínez, in which the photographed waves become folds in an infinite sheet. Hers is a universe of rocks, water, light, curves, and hands. Martínez—creator of light—folds and unfolds the limits of the image.

Upon entering, two hands hold the curved universe against a pitch black background. On the other side, the water between the stones hides a sun that winks in black and white against a territory without scale. The image is not hung in the center of the wall; behind, a window is hidden and on the sides it is wrapped in light.

Around the room there are stones that are so stoney they seem to come out three-dimensionally from the images, scratching the eye that views them. The eroded eye is also flooded, seeing seas so clearly that they become matter. The words “erosion” and “error” are read on the wall labels; the eye-rock-sea is understood to be the result of the active act of looking. The images are geological, magnetic, and erratic explorations.

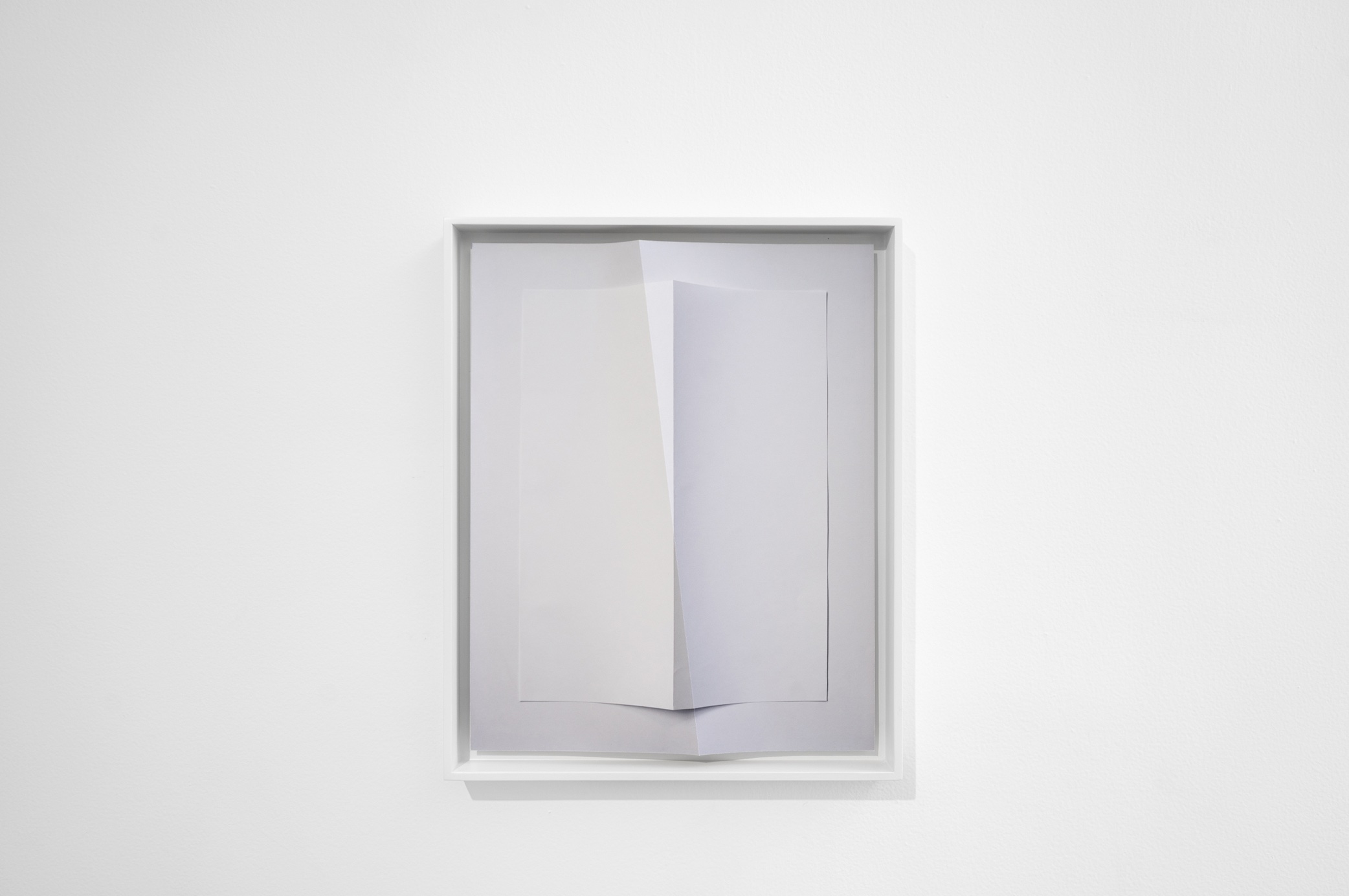

Suddenly the eye thinks it has found a place to rest: three nearly white frames inhabited by folded sheets of paper, and here as well we find no optical repose. Within these frames lies the claim that printed photography is paper and that seeing a photographic image is seeing an object. The eye does not rest at these targets because there is an almost magnetic error in them: the photographed and printed fold does not match that of the paper. The lag is subtle and incredibly uncomfortable—the eye reacts to the mismatch. Let us recall the initial image in which the hands held a perfect curve, round like a planet: and let us imagine those same hands folding the paper: a nod to the body—not just the eye—that operates the camera. The photograph is a photograph, but it is also a light sculpture.

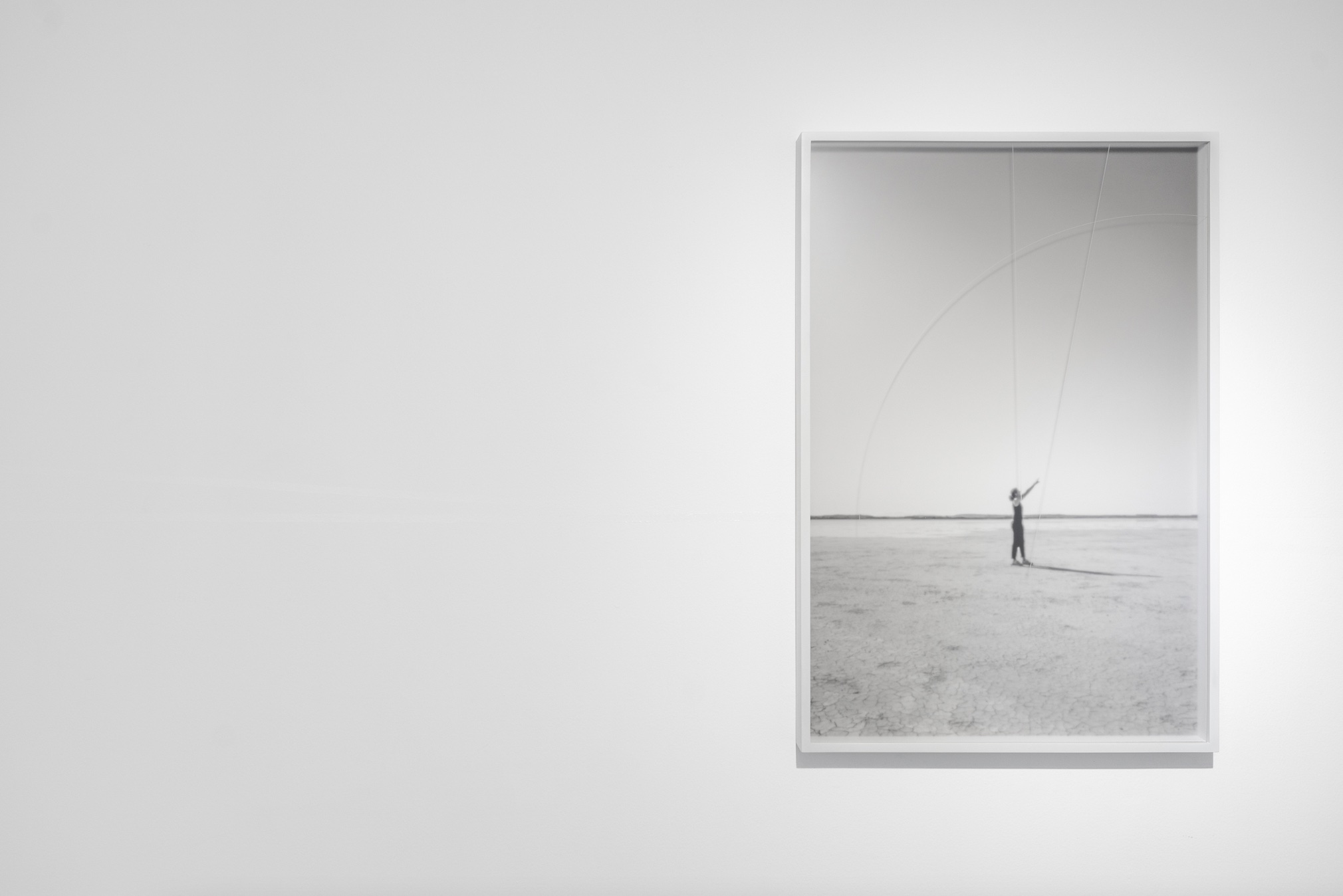

In the next room, the body appears. It is no longer just the body of those who visit the exhibition, but also the body multiplied as image. We see it portrayed while directing the space inside the photo with its hands. At the bottom of the two images—in which the same figure is seen in two very similar spaces—a black horizon can be glimpsed, dividing the image plane. In the center, the portrayed body is established as vertical, facing the landscape. Above, a sun can be seen that manages to shine warmly among the grays and that causes a nearly perpendicular shadow. Within the images, the figure raises its arms, denying gravity. The two gestures—each slightly different—recorded by the two photos are emphasized by the assembly in the frame. We discover that the gesture is not only internal to the image but also external to it.

There’s an overlapping of material territories between the “beyond” of photography and the “here” of the material. The glass that covers the printed and framed image has vertical curves and lines carved into its surface. And the sgraffito transparency of the glass reveals something else: Martínez tells us that glass is glass, as well as space. When we recall that we are in the gallery and that these world-images are hung on a wall, a slight flash forces us to prolong our gaze, as the images are projected outwards.

We return to the first room. While all the photos continue to wage a highly ordered battle between stone, water, and light, a subtle revelation appears: the short boundary between floor and wall is highlighted with a powder between blue and violet. It is then that we travel through space not only as an eye, but also as a body. The gallery becomes a territory, invading us with the intolerable question: where does the landscape begin and where does it end—if ever?

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on June 28 2023