Article

Ana Segovia’s La Faena | A Blood Rose for Him

by Sandra Sánchez

The need of a funeral for machismo puts the certainty of the painting at play

Reading time

6 min

In the Centro Histórico of Mexico City, there’s a beloved cantina where we never fail to encounter artists from the local scene: La Faena. It’s a place where dust mixes with furniture belonging to a time that seems more bourgeois intellectual than present-day office worker or freelancer. In La Faena different groups gather to drink cold beer (day or night), all to the rhythm of a jukebox that offers everything from The Cure to Shakira. One has a good time there. If there’s drama, the place contains it; if there’s enthusiasm, the place stimulates it.

Ana Segovia is a painter who in recent years has produced art that’s been talked about here and there. Her palette balances together festive, saturated, and vibrant colors that are far from solemn. What is most attractive about her work, however, is the way she offers a critique of machismo through an acute analysis of the visual performance that this attitude entails. In past work, Ana has dismantled the masculinity portrayed by protagonists of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema. It’s task carried out by paying attention to the way men relate to their bodily positions and to the women they seek to stalk and “conquer”. In the paintings we also find an analysis of details that shape this masculinity in things such as clothing and accessories. Another important element is the space where each scene takes place, which the artist studies symbolically, as it is never something neutral.

Whenever Ana goes to La Faena, her painter’s eye insists on settling again and again on a large-format painting (233 x 510 cm) located in the main hall. The work is signed CCC. Cornejo M. Next to the signature is the date: 1965. In her search to discover Cornejo’s whereabouts, which proved fruitless, she learned that the song “Huapango Torero” by Lola Beltrán inspired the painting. This datum opened up meaning. Such was Segovia’s fascination with the picture that in rapture she tried to buy it. Of course, the waiters at La Faena, who are not employees but members of a cooperative, told her no: the painting is as important to the premises as the jukebox or the beer. Ana understood the situation and waited.

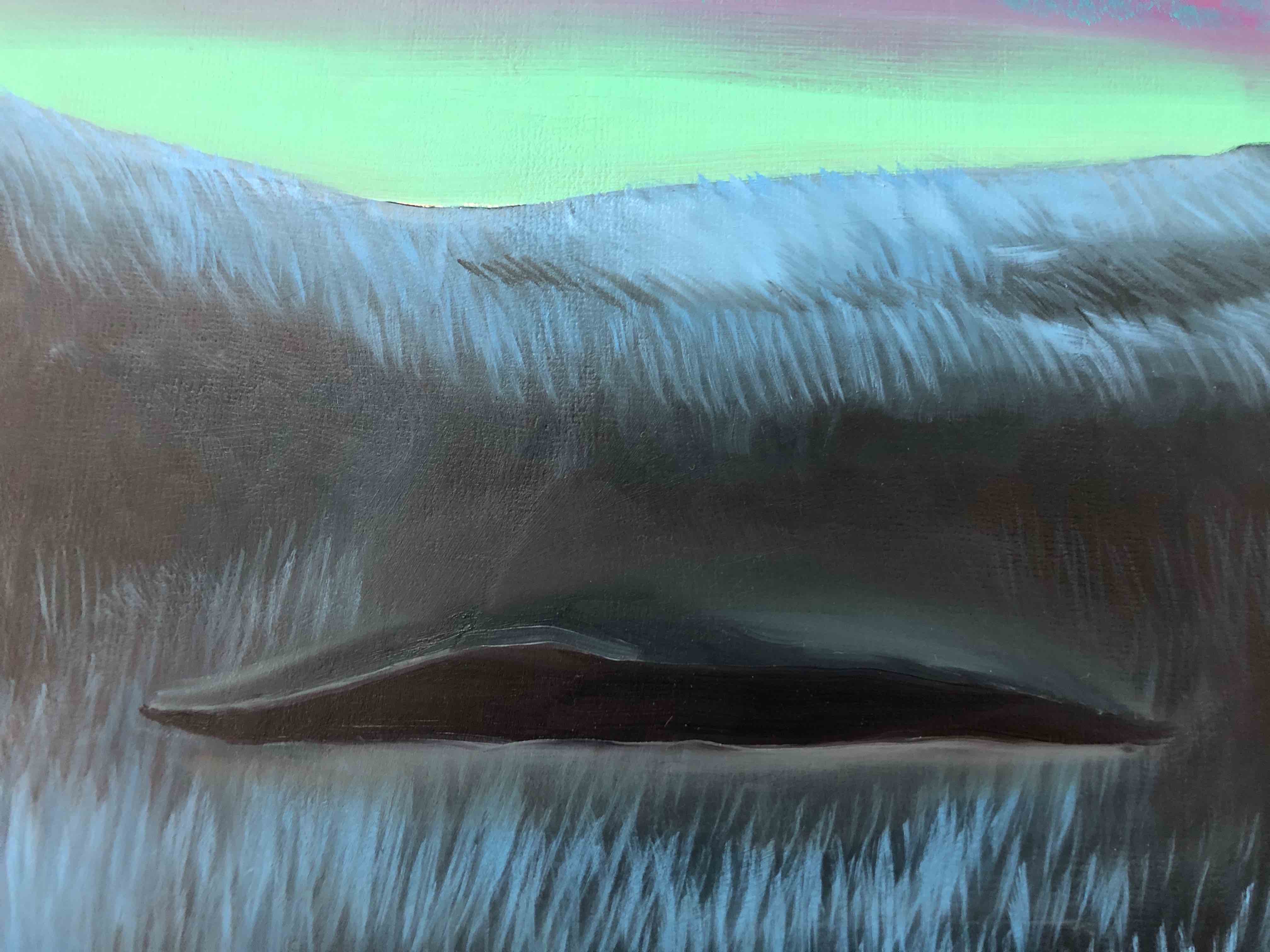

After going over the matter, she decided to do it all over again and paint the picture for herself. The first challenge was to get a large enough studio to accommodate such a painting; she found the answer in Lagos. At first, the painting was burdened by its resemblance to the original. Ana had not managed to give the painting its free individuality. After working for weeks, she was able to decipher what the painting meant to her: a farewell, a funeral for a particular type of masculinity: the macho. For the artist, this event should convey neither nostalgia nor sadness. She opted for a more festive tone for the ceremony instead.

In the original painting we see a boy trying to enter a field intended for raising bulls for the Fiesta Brava. In the background we see the animal, with his sharp horns. The boy is captured just at the moment he opens two lines of barbed wire in order to make a hole the size of his body, allowing him to cross over to fight the bulls, to rehearse a future.

Ana takes the figure of the boy and turns it into a self-portrait. Gives him her cap, her work boots, and decides that with him, through him, together they will cross over. In the picture she does not seek to bullfight but rather to bring about another scene, one without a ring. She wants to understand what the beast wants; knowing the risk involved, she carries a white handkerchief in one hand. In Ana’s field, unlike Cornejo’s, roses have grown. Full roses and red roses, outlines of roses; roses being born: tentative, barely delineated strokes. In her other hand, Segovia carries an intensely colored flower. A blood rose for him.

The need of a funeral for machismo puts the certainty of the painting at play.This uncertainty manifests itself in the impossibility of knowing what the reaction of the patient one waiting in the green field will be, the one who looks at us, head-on, with his horns ready either to give truce or to charge. Maybe the young person in the scene will manage to cross, or maybe they will stumble; their pants get stuck to the barbed wire, which threatens one of their ankles.

The Party

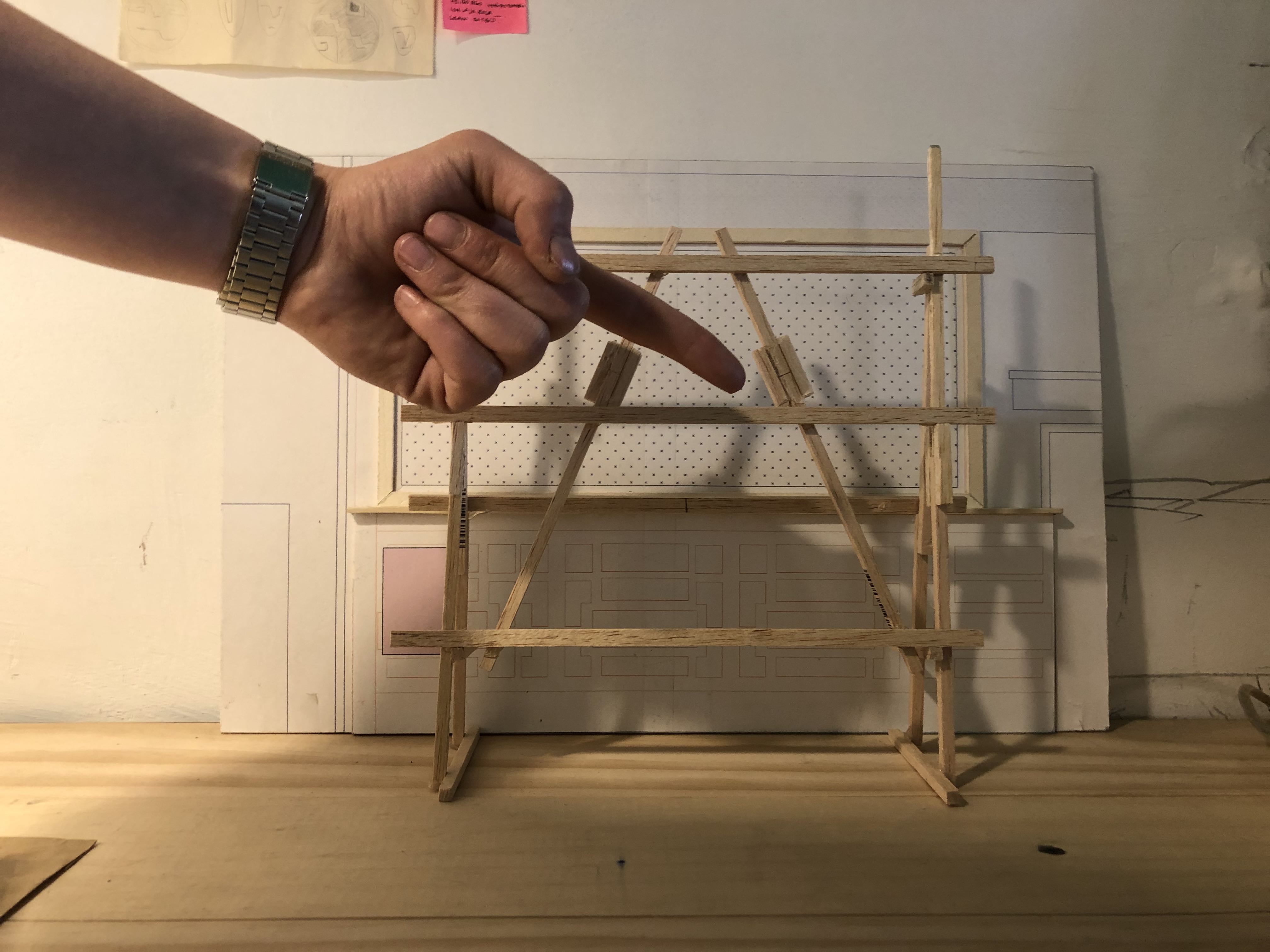

Ana discussed her idea with friends and with friends of friends. Little by little she took on collaborators, such as Alvaro Castillo who had to speak with the place’s manager in order to secure the deal. Then the project needed two designers: Fernanda Itzel González and Mario Rodríguez Jaramillo, who also joined the conversation. Between them they bounced ideas for mounting the painting, something that faced several restrictions: nothing could be nailed to the wall or hung from the ceiling.

The solution was to build an easel that would serve as a support for the new painting, thus also establishing a spatial dialogue with the original, which would not be dismounted. The easel preserves the structure, but it also houses another tradition on its surface, namely that of the floral arches used in patronal feasts in various parts of the country, as well as in Mexico City. Boroughs such as Xochimilco and Iztacalco claim, rightly, to be experts.

The easel will not only support the painting two meters above the ground, but will also hold natural and artificial flowers that echo those arches and their symbolic ambiguity: they are used as much for funerals as for celebrations. For this process another collaborator, Mario Arturo Aguilar, a specialist in these arches, was summoned. He follows his father and grandfather in this trade. He has won important prizes defending Iztacalco from its florist rival: Xochimilco.

Fernanda and Mario proposed that Ana, in decorating the easel with flowers, not only think about the arches but also about the role of flowers as ornaments in Mexico. There are flowers everywhere, in pre-hispanic pieces, in wooden toys, and in almost any element of Mexican popular culture.

Ana accepted the idea with pleasure and decided that the project no longer belonged only to her. If La Faena is for everyone, then so should be the painting: receiving and summoning whoever may feel comfortable in that space, in that work of art. The artist says that the installation is not a spectacle, but rather an invitation to consummate a movement towards another type of self-recognition. That is why her collaborators decided to place mirrors between the flowers, so that each can see what they may like or need. Before that profane altar a transition is collectively invoked: that of the end of a performative way of relating to one another, in order to give rise to another scene, one into which we deposit desires and demands without knowing specifically what will come to us.

Published on February 1 2020