Interview

Love, Affects, and Revolution: An Interview with Dora García

by Verónica Guerrero Molina

Reading time

7 min

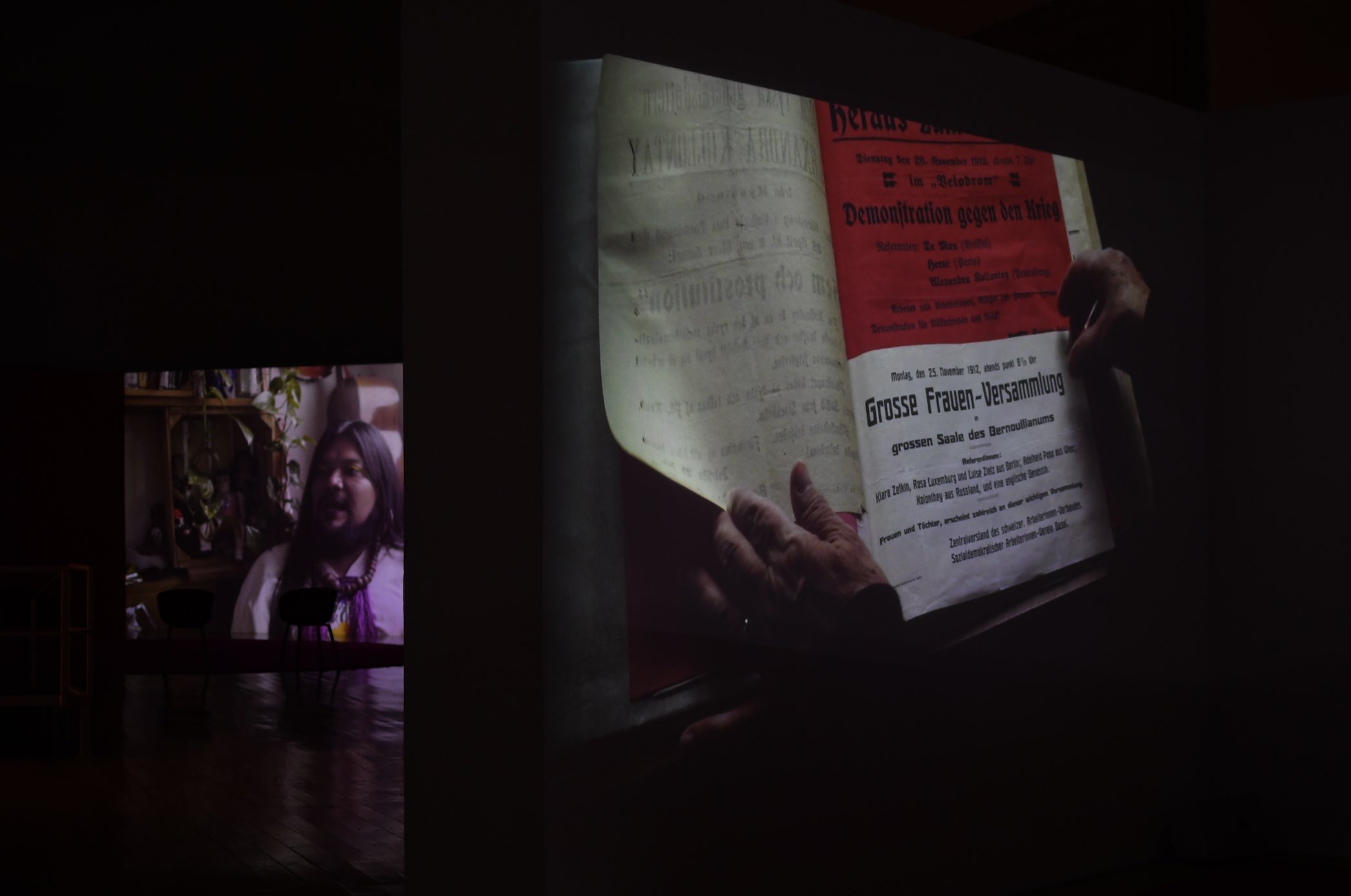

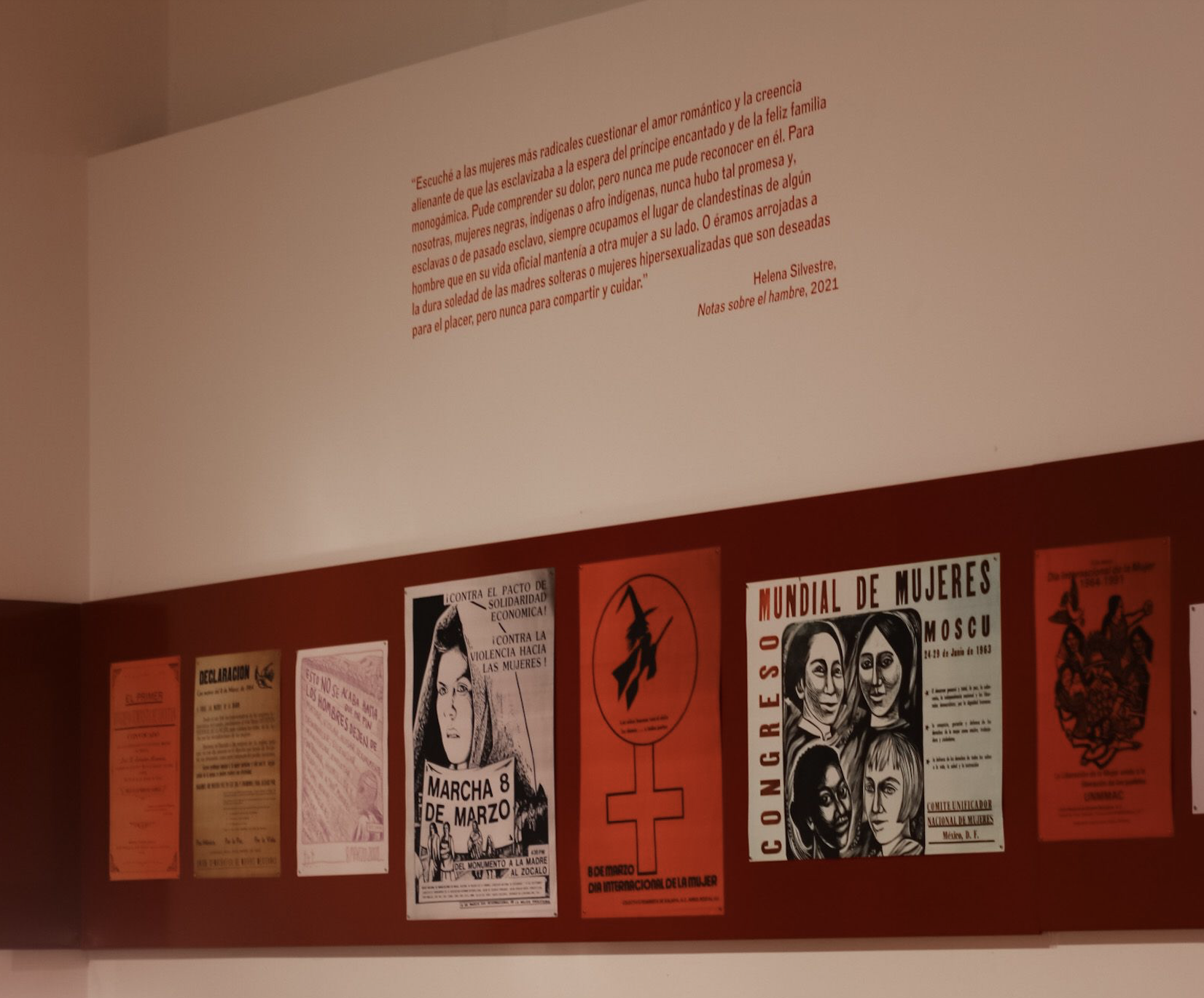

At Laboratorio Arte Alameda one can currently visit the exhibition by Spanish artist Dora García, Amor Rojo, in which three of the museum’s rooms have been transformed into spaces for projection as well as bibliographic consultation. I had the fortune of spending time with García for a chat in which art and writing made it possible to get closer to the fascinating Russian revolutionary Alexandra Kollontai: born in Moscow in 1872, she played an active role in the 1917 Russian Revolution and was a faithful defender of women’s liberation. In addition to her writings, she is known for being the first woman in history to head a government ministry.

Verónica Guerrero. Dora, in your body of work one can see your preference for certain formats over others. You seem to feel comfortable inhabiting performance, happenings, installations, and digital media—to the detriment of other media such as painting, sculpture, and drawing. Is there a reason for this preference? Can you tell me a little more about your decision to use video for this latest work, Amor Rojo?

Dora García. The idea behind Amor Rojo has always been a filmic investigation generated by a research team, composed of four Mexican women (1) and myself. The reason for bringing in Mexican researchers was that they could arrive at certain understandings that I could not. With a basis in the idea of a single film, in fact three different films resulted. The truth is that I am very happy with the outcome. This is practically a collective exhibition since, in addition to the films involved, the presentation of the archive and the public program are of equal or even greater importance. The result is an exhibition with the three films presented as projections: that is, Amor Rojo amounts to installations in the space of Laboratorio Arte Alameda, together with the public program and archive.

VG. Amor Rojo left me not only with many concerns regarding the presentation format, but also with many questions regarding the role of writing as a memory device and archive, and also as a motor for generating artistic creation. The concept of the diary and of intimate writing is something that recurs throughout your works. In this most recent one, it’s taken up once again with the reading of Alexandra Kollontai’s personal correspondence. Why did you decide to focus your gaze on this Russian revolutionary? What interests you about her?

DG. In the first film, titled Love with Obstacles, there are some of Kollontai’s handwritten letters, which also appear in the last film, not in images but rather through a voice that reads them. In other words, correspondence is something that’s kept up.

I started reading about the figure of Kollontai four years ago, which coincided with what would be called the “Marea Verde,” or “Green Tide,” in Argentina. In Spain, these were very important moments for feminism following the famous trial of “la manada,” and, in addition, the first feminist strike took place. Reading Kollontai was something I took on in Stockholm, where she’s well-known, so reading her was a coincidence. At the beginning, I saw many things that a hundred years later seem very contemporary to me and that have a lot to do with the feminism that’s being discussed at this moment. The idea of the family and of romantic love as instruments of oppression were very present in classical feminism—what’s called “Second Wave” Feminism—and yet Kollontai had already brought them to the fore. This is how I began to get interested in her ideas and what she represents, since she’s a very interesting character from many points of view: the role she played in the Soviet Revolution, and then the “perishing” of the dream of communism. I made many connections that have mattered to me and that have been present in my work.

VG. You know, Dora, that same year two books fell into my hands in the context of the feminist strikes: The Autobiography of a Sexually Emancipated Communist Woman and Communism and the Family (2). For me it was a discovery: an author who had never been on the map in my academic approach to feminism and gender studies. Kollontai does not fit into any of the waves of feminism, and this made me think about the epistemic violence contained in the narrative of the history of feminism that exclusively locates the enclaves of advancement and knowledge in the West.

It seems to me that one of the ways of approaching Amor Rojo is to understand it as a hermeneutic exercise, as a rereading of an author like Alexandra Kollontai using the conceptual tools of the present. What does it mean to work with an author like Kollontai within a Latin American context like that of Mexico?

DG. The fourth feminist wave, which we’re currently in, seems to me to have a lot to do with the fight against colonialism, with post-colonial struggle, and Latin America seems to me the locomotive of this struggle. This affirmation seems undeniable to me, based on my experience. In Mexico, but also in Argentina and Chile, violence is identified with a State that is comfortable with and happy with patriarchy. This makes it the case that demonstrations tend to occupy space in a meaningful and interesting way: the language used, the slogans, the chants, what’s written on the posters. In the demonstrations in Germany or Switzerland that I’ve attended, slogans are sung in Spanish.

In addition, Kollontai was the USSR’s ambassador in Mexico. It’s true that she only spent six months in the country, but it was a very important historical moment when the Mexican Revolution was in a process of institutionalization and the Russian Revolution was in a process of degradation. It was a moment of personal and professional disappointment for Kollontai, who nevertheless always remained firm in her duties and convictions, for which we continue struggling a hundred years later. Abortion was first decriminalized a hundred years ago in the USSR, something we continue fighting for today.

VG. The relevance of her thought is clear to me: Kollontai is an author who advances many concepts and problems, such as critiques of the family and of love. I have the intuition that the question of how to organize affects and care is fundamental to our time, since it’s the deepest and most transversal question. I mean, making the system compatible with life in every way implies a radical confrontation with the necropolitics in which we’re now immersed. From what you’re telling me, Kollontai is indispensable for rethinking new ways of organizing affects.

DG. I believe that from Kollontai there are two practically identical concepts that have survived over time. The first is that of comradely love: the idea that the bourgeois couple and family what we now call heteronormative constitute an obstacle to the emancipation of women and, therefore, need to be rethought. The concept of amor camaradería is what we would now call radical tenderness.

The other idea from Kollontai that’s current is that not all women have the same interests simply in virtue of being women. She would talk about differences in the interests of working women, and we would now add the interests of racialized women, migrant women, those stigmatized by prostitution, lesbians… That is, the fact of being a woman intersects the types of oppression to which she’s being subject.

Kollontai herself said—and it’s something we can’t forget and won’t forget—that the aim of bourgeois women is to maintain their privileges, while ours is to totally change the system.

1: The Amor Rojo research team has been made of up Carla Lamoyi, Olga Rodríguez, Paloma Contreras, and Rina Ortiz, as well as the artist Dora García.

2: The Autobiography of a Sexually Emancipated Communist Woman can be read at https://www.marxists.org/archive/kollonta/1926/autobiography.htm. Communism and the Family can be read at https://www.marxists.org/archive/kollonta/1920/communism-family.ht

Cover picture by @photo.eraa. Courtesy of Laboratorio Arte Alameda

Published on January 19 2023