Essay

Around Its Center, the Dream Called Ourselves

by Cristina Torres

Reading time

4 min

It’s difficult to talk about something unprecedented while it’s happening. What’s lost is critical distance, though what’s gained is shared terrain. For someone who writes art reviews, the relocation of the art world to the language of coding and programming means in part that the distance between you and me has become curiously shorter, thanks to the fact that we both access works from a screen.

Our approach to art has long been mediated by screens, projectors, and books that persuade us to seek, talk alongside, study, and remember certain works. I remember, shortly after finishing my university studies, hearing the curator and artist Tonatiuh López clarifying that we had completed a degree, not in art history, but in the history of art images. For a certain point of view, this displacement produces an aporia between art’s material dimension and its iconic image, as in the paradigmatic reflections of Walter Benjamin and, later, Boris Groys on the role of specificity and context in artistic experience.

Part of the discussions taking place these days occurs within this question’s dichotomy, in the gap created by the recoding towards digital images and domestic isolation. In comparison, a verse by Tristan Tzara:

“I speak of the one who speaks I am alone”(*1)

Recently, in the talk “How Will Bodies Coexist When Museums Reopen?” (“¿Cómo convivirán los cuerpos cuando los museos reabran?”) from the initiative Museos 3.0 #MUS3OS, Silverio Orduña has emphasized the incapacity with which museums have dealt with the body in general, while Mariana Arteaga has emphasized the need to expand what we call the body in the museum (taking into consideration workers, for example) and to observe critically the ways in which bodies are shown on the pandemic internet, as the predominant frontality that points towards the spectacle.

“The complex of law, economy and spectacle is a crux of mediation. It exhausts language. Public reason cedes the ground to the performance of subjectivities and coded games. It resembles fascism because it is hostile to life, but it kills meaning and soul before it kills people. It produces a global sadness in a way that the historical tragedy never did…Whatever happens, language must remain close..” (*2)

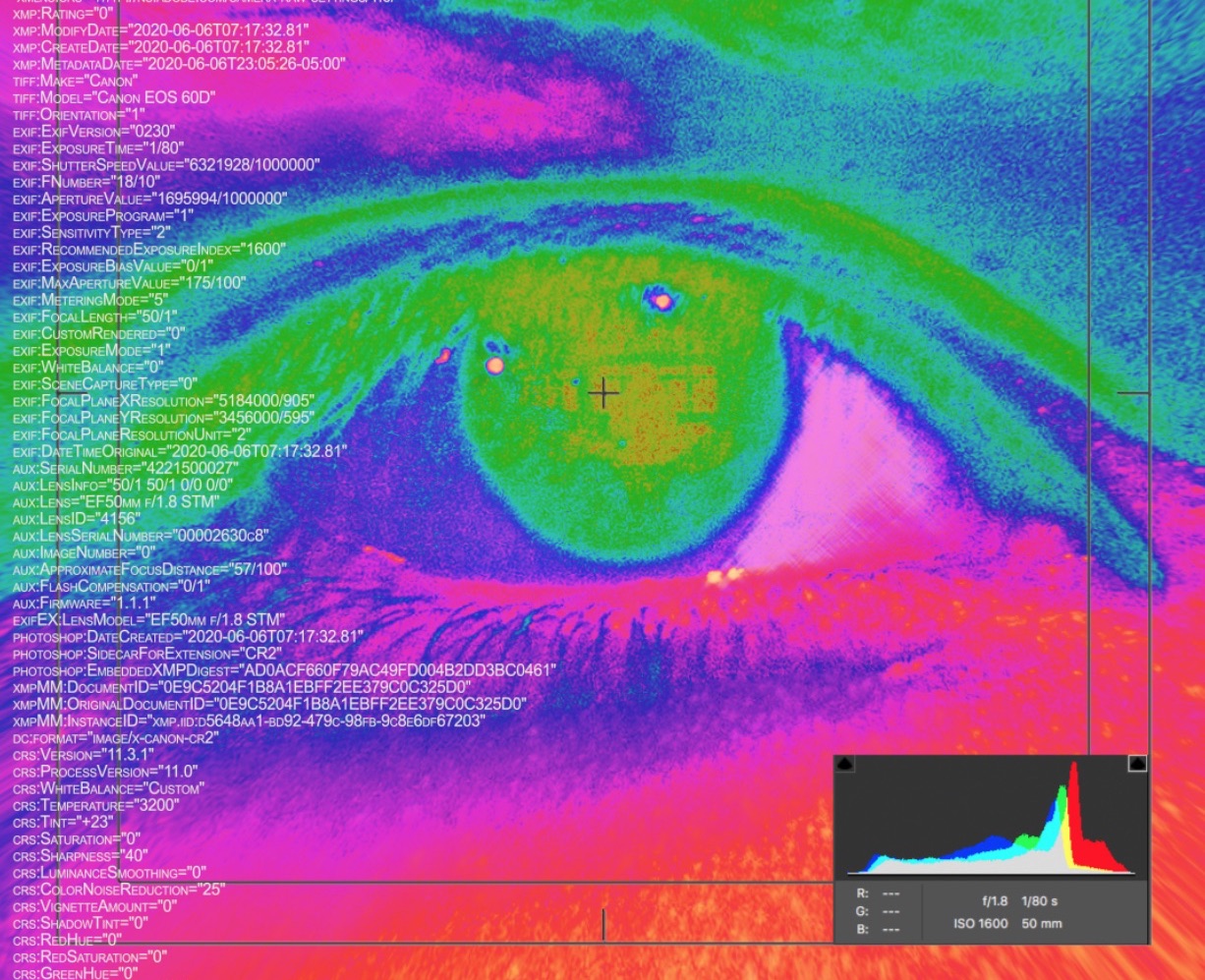

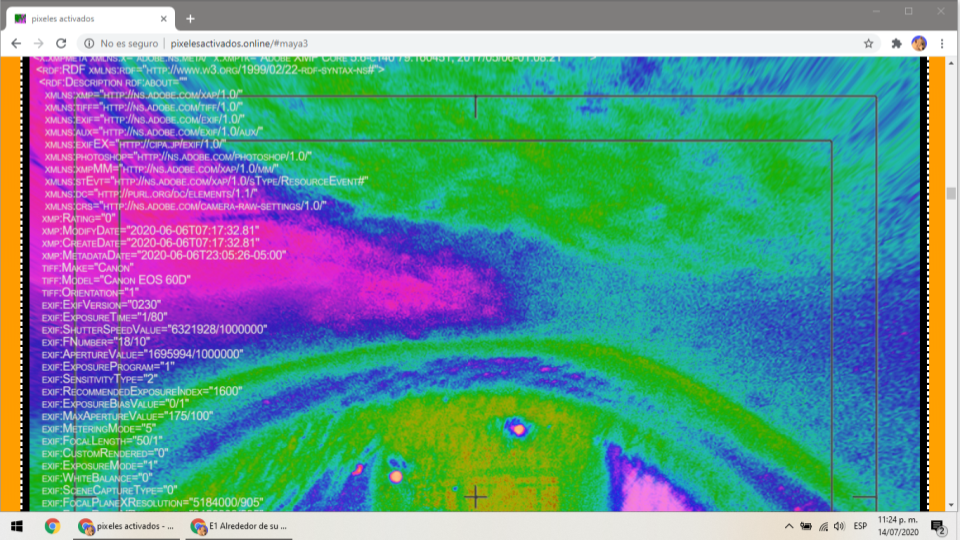

At another point on the spectrum are the artistic practices created from, for, and on the internet and the digital environment, in a sense more habituated to inserting themselves into domestic intimacy. We traverse through clicks that activate instructions in code, as well as through scrolling, a mode of reading that has endured from the parchments of antiquity. Exhibitions downloadable in PDFs of variable quality such as Permanencia voluntaria at the Centro de la Imagen, hyperlink exhibitions such as Playtime at the Casa del Lago, “reality show” exhibitions such as Mario García Torres: Solo at Museo Jumex, as well as exhibitions on a reel such as Pixeles activados and rendered exhibitions such as A través by Arantxa Solís, both at Casa Equis. The art space’s virtuality is made concrete through various hinges among the possibilities of programming languages, the memory of the gaze, and, on occasion, the nostalgia of white architectures in which there is no night.

Merecemos fracaso / merecemos ocio (“We Deserve Failure / We Deserve Leisure”) by Miriam Gómez, alias “El pinche barrendero” (“The Fucking Sweeper”), offers another escape route. Curated by Karla Noguez, the closed-door exhibition takes place in the physical space of Estudio Marte 221; however, according to the curatorial text, “it does not seek to be visited but rather deduced…In this sense, it invites the possibility of knowledge through supposition, the experience of doubt, obliquity, improvisation, and from the current sensation of displacement of our image of the world.” In this sense, the problem is less the electro-reality of art than the category of certainty.

Before the pandemic I had the opportunity to collaborate on a project in which we reflected on certain aspects of the history of the gaze, especially the framework bequeathed by a certain theory[3] that centuries ago determined that art should be conceived as seen from a window and projected from a grid onto the static gaze of the beholder. It’s curious to think how the “zoom out” imposed by corporeal distance reproduces and launches this operation towards whatever electronic rectangle it may be from which we now peer at the image.

(*1) This verse, like the one that lends this essay its title, comes from “Approximate Man” by Tristán Tzara. Translation by Mary Ann Caws.

(*2) Soren Andreasen and Lars Bang Larsen. The Critical Mass of Mediation, 2014.

(*3) Leon Battista Alberti. Della Pittura, 1436.

Published on July 17 2020