Review

A Long Farewell to Telenovelas: Melodrama at Unión

by María Emilia Fernández

Reading time

8 min

Telenovelas were forbidden in my home. There was no eating or doing homework in front of dramas born from “real life,” full of passion and unbridled violence. Both my mother and my father considered them practically harmful to one’s health, though I must confess to having seen more than one episode in secret, seized by a mixture of morbidity and curiosity. I have no doubt that those scenes have had an impact on my sentimental education; for many others they were an entire school of emotion. What does anger look like? What does sadness sound like? What does disenchantment taste like? And, of course, how does one recognize true love?

We no doubt owe a great deal to the melodramatic tradition in mass media (movies and telenovelas, not to mention comic books, songs on the radio, commercials, and ads), but I think there’s no negligible amount of all this that we would prefer to discard from our unconscious. The screen is a stage where collective imaginaries take shape, where many of society’s expectations and wishes are formulated and represented. Nevertheless, this is also where the values and structures of patriarchy, such as gender roles and romantic love, have been reinforced. Melodrama, an exhibition organized by Juan Pablo Ramos at Unión, brings together recent work by seventeen artists seeking ways of renegotiating and relating to this legacy. The show presents work by a generation born (for the most part) in the early 90s, who witnessed telenovelas’ decline, something like the beginning of the end of their golden age, when telenovelas practically conquered the world.*1

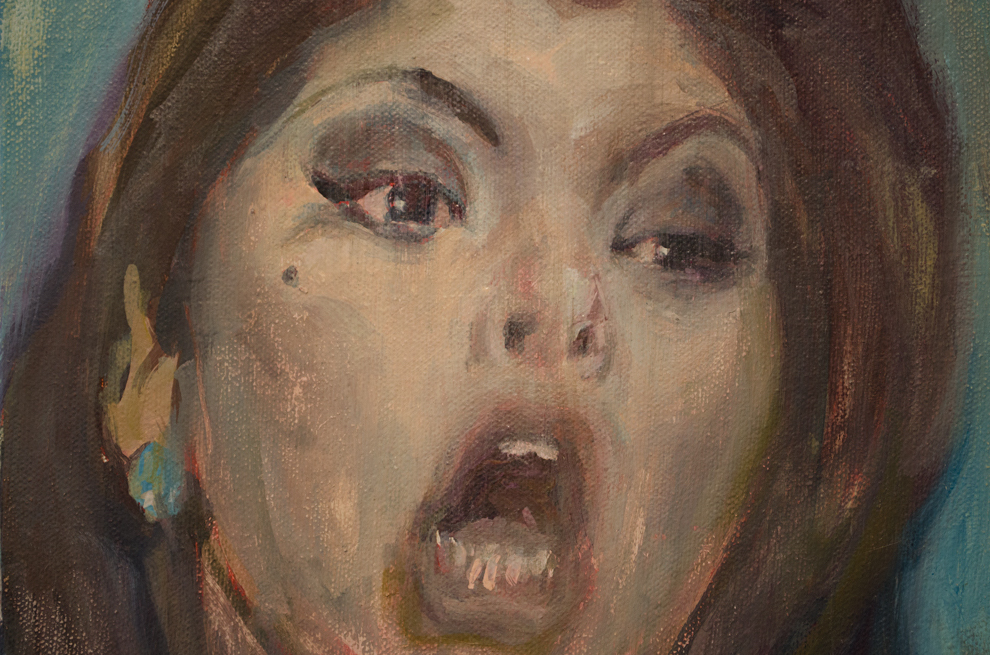

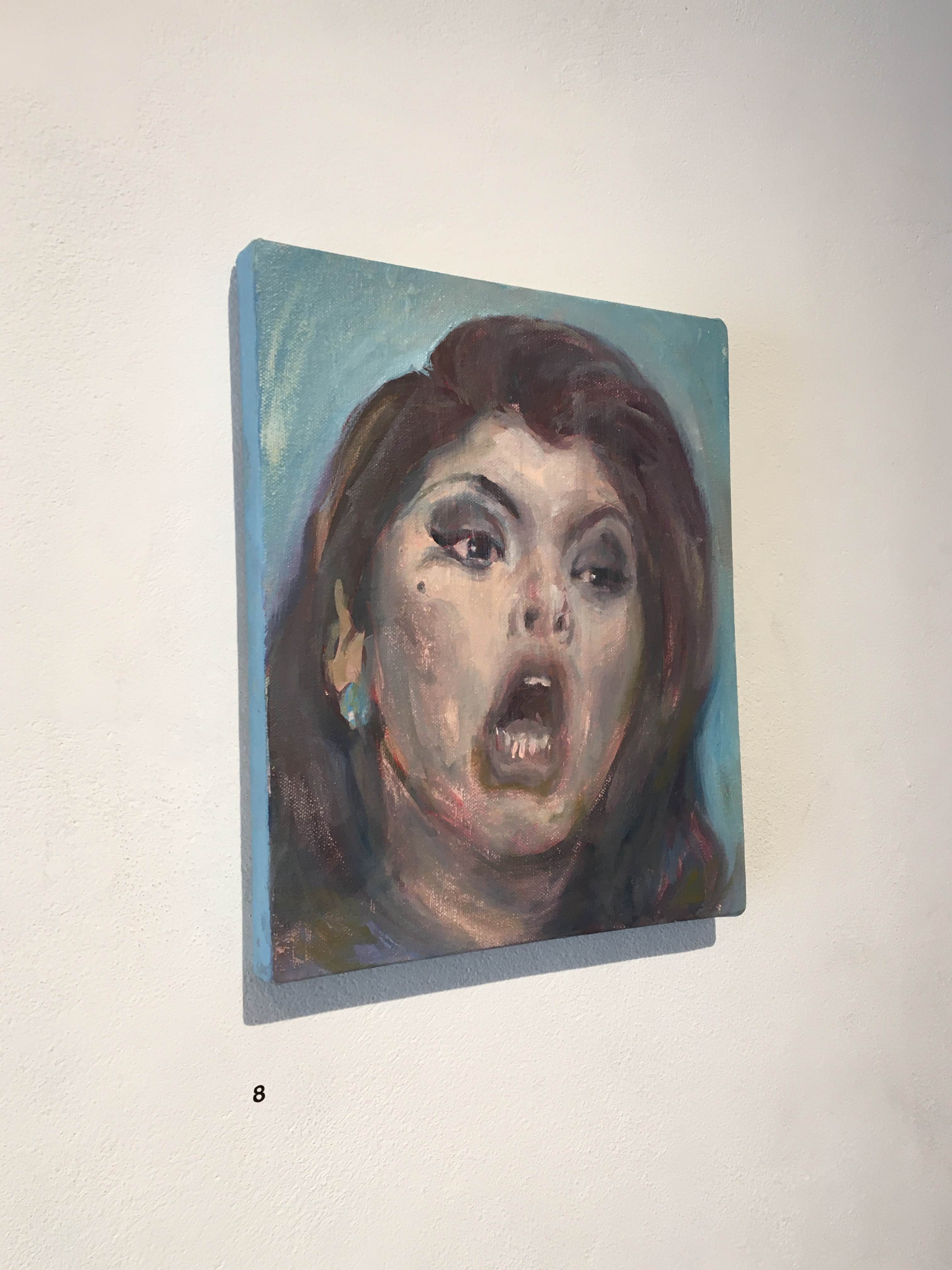

This generational difference is reflected in paintings such as La gritona (“The Screaming Woman,” 2020), by Anais Vasconcelos. This piece portrays a key moment in the telenovela María la del barrio (“Humble Maria”), in which the villainess, Soraya Montenegro, finds her beloved Nandito kissing Alicia, known as “the damn cripple” (la maldita lisiada). The scene was not just memorable in its time, as actress Itatí Cantoral’s alienated scream has since become a meme in its own right, an ultra-sweetened version of itself. Vasconcelos’s work immortalizes this face disfigured by contempt, but also resignifies it via the pictorial medium. By representing a picture inside a TV sequence with such seriousness, in a style reminiscent of German Expressionism, La gritona allows us to reflect on the weight and influence of certain images on others, especially in art history.

The exhibition features works with sensibilities that could be considered cursi, kitsch, camp, or queer. These concepts allow one to conceive forms of subalternity from within pop culture; according to Paul B. Preciado, they’re concepts that “appeared in the artistic discourse as part of a broader larger epistemic apparatus in order to draw borders between what is natural and what is original, operating as instruments of moral or clinical diagnosis aimed at detecting perversion and deviation.”*2 As such, they “signal all that which exceeds the new bourgeois, urban and capitalist masculine figure of the virile, white, heterosexual man.”*3 In this sense, the melodramatic becomes another way of criticizing patriarchy and dislocating the norms of a genre that, for decades, marked mass culture in Latin America.

For example, some pieces portray living media icons, such as Jaime Maussan and Juana Judith Bustos Ahuite, better known as la Tigresa del Oriente (or “The Eastern Tigress”), while others translate, using oil or Prismacolor colors, scenes from movies and TV shows. For its part, Chino Solís’s candle refers to the death of singer Jenni Rivera, who ate dinner at an Oxxo before boarding a plane that would crash on the night of December 9, 2012. Filled to the brim with monosodium glutamate and paraffin, this shrimp Maruchan takes on a dubious solemnity, becoming a kind of relic of infamy that brings us closer to the icon of Sinaloan Banda music. In the exhibition, the otherness of these “styles” or of these melodramatic aesthetics becomes a way of questioning or reevaluating what has been traditionally deprecated as low culture, transforming it with a sense of humor and irony.

_por_las_facilidades_otorgadas_para_la_exhibicio%CC%81n_de_este_video%5D.png?alt=media&token=b2f7c825-1ab0-4239-8a33-dd69e79d4768)

The selection of work is characterized by its ambiguity with respect to telenovelas and to TV in general: it’s not clear whether the artists have devoted themselves to parody, criticism, homage, or a mixture of all three. Perhaps the one work that presents a more openly critical stance is Sí señor (“Yes, Sir,” 2014-2015) by Abigail Reyes (click here to watch the teaser), which highlights how culebrones (long-running soap operas) have fostered the submissive and subservient character of women. The video features scenes in which female characters respond affirmatively, unable to express any disagreement with men or authority figures. This piece awakens in me a combination of silent rage and indignation, something hard to forget. The implicit question is, “How does one not replicate forms of behavior that we have seen over and over again?”

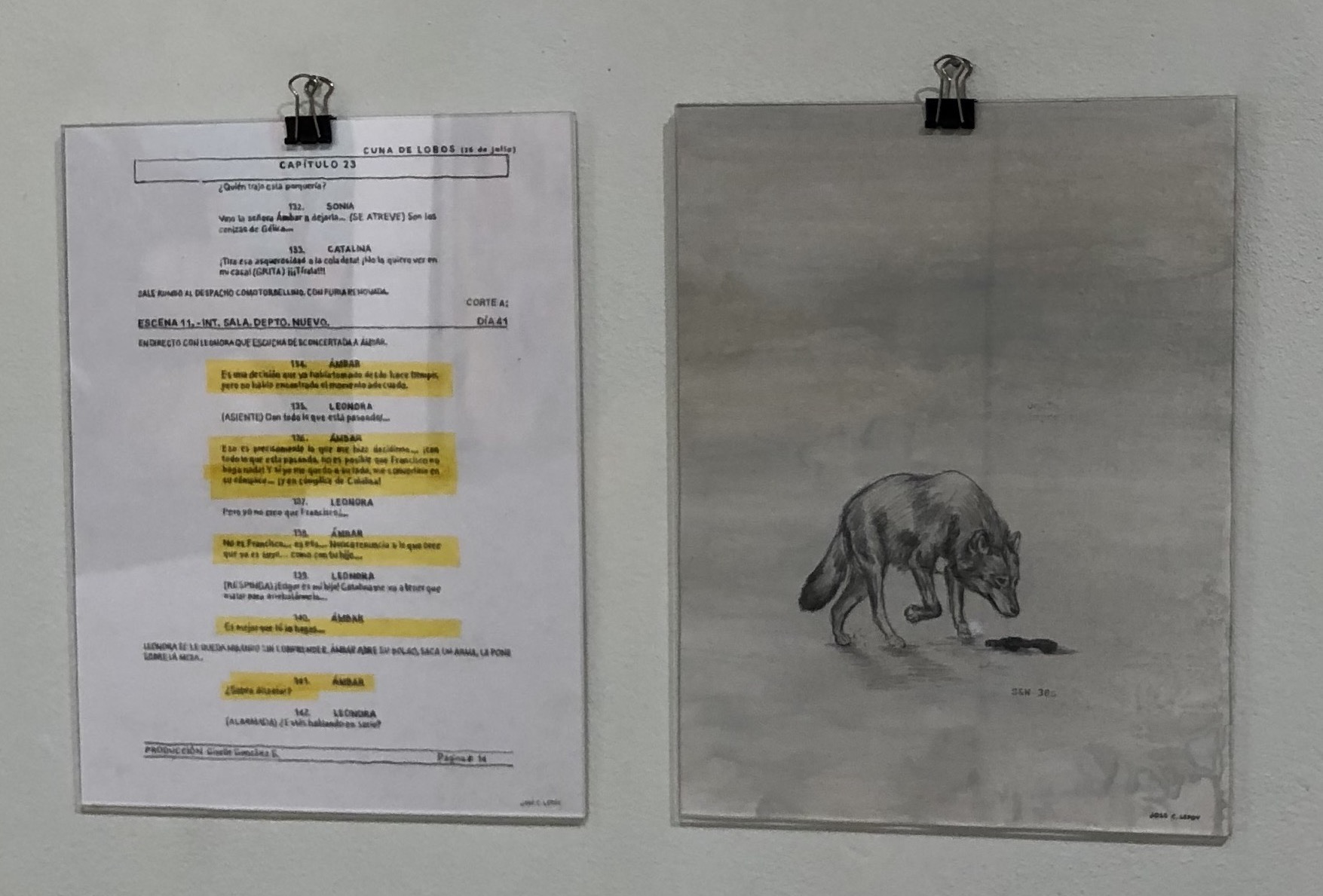

But Reyes’s video is the exception to the rule, as it would seem that the artists, empowered by other stories and TV content, don’t possess the urgency or need to condemn melodramatic productions in an emphatic manner. Other pieces adopt a different strategy, as is the case with Jose Castañeda Lepov’s work. He exhibits the behind-the-scenes of telenovelas, letting us see a hand-drawn script sheet from Cuna de Lobos, in which one can read the character Ámbar’s dialogues. Highlighted in yellow, as if they belonged to the actress, these lines and scene directions allow us to appreciate the drama in its maximum splendor, even while maintaining a rather analytical distance.*4

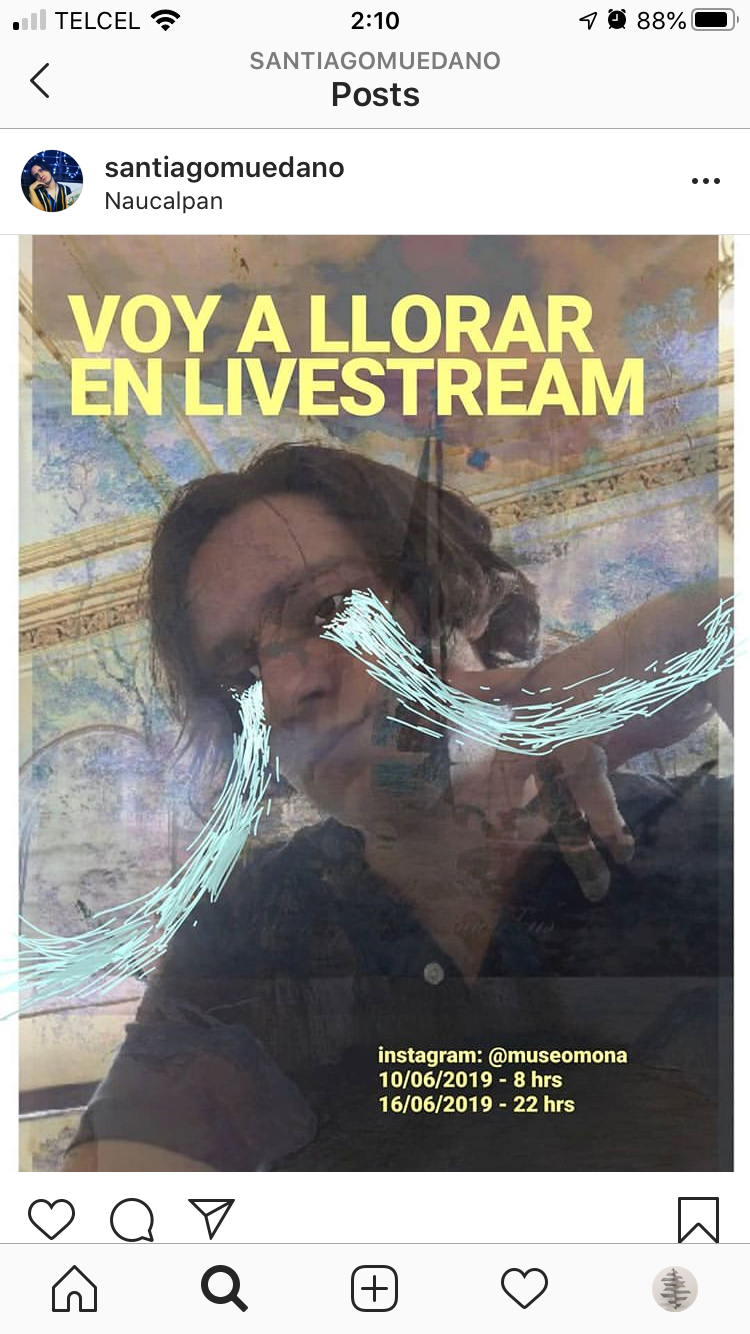

Another case is that of Santiago Muedano, who shows off his melodramatic skills while crying in an Instagram live stream. Muedano’s work alludes to Bas Jan Ader, who in 1971 documented his inconsolable crying in both a series of photographs and a silent film in black and white. Bas_jan_ader_REMIX.mp4 (no es que esté demasiado triste para decirte, pero últimamente estoy harto de mi propia voz) (“not that I’m too sad to tell you, but lately I’m sick of my own voice,” 2019) takes up this gesture, but without the confessional tone of Ader’s title. His is a performance that doesn’t purport to appeal to blackmail or to the viewer’s genuine sadness, but instead openly dramatizes the exhaustion that many of us feel when faced with the constant pressure to communicate and represent our moods on social media. His proposal starts out from his being able to name that feeling and that discontent in order to communicate it to an audience without having to go through a Televisa script.

As I go through the exhibition, I realize that the problem with telenovelas is not only their stories or how they are told, but also that they seem to be the only stories possible, or those that have prevailed to the degree of making all others invisible. Today there exist many other channels of individual expression, and perhaps telenovelas are losing strength precisely because they are no longer the only stories told, and nor is TV the only medium that validates our wishes and expectations. From this point of view, melodrama is no longer a dangerous threat to our emotional intelligence, but rather is gradually giving way to irreverent, nostalgic, or perhaps even tender readings of TV pop culture.

Melodrama suggests that succeeding generations have wagered on the natural erosion of telenovelas, on a slow and constant loss of their hegemony and control over society. If the death of melodrama is due to natural causes, then it can be celebrated with pastel colors and a long farewell party, or with exhibitions like this one.

The exhibition can be viewed up until August 13, 2020. The participating artists are Abigail Reyes, América Gonzalez, Ana Armitage, Anais Vasconcelos, Chino Solís, Daniloween, Edrey Cortés, Enrique López Llamas, Fernanda Acosta, José Castañeda Lepov, José María Candas, Museo de la Corrupción, Nicole Chaput, Santiago Mora, Santiago Muedano, Víctor Alvarado, and Zyanya Arellano.

*1 It would be difficult to compete with the furor caused in Scandinavian and Eastern European countries by such telenovelas as Cuna de lobos (“Cradle of Wolves,” 1987), Simplemente María (“Simply Maria,” 1989), or María Mercedes (1992). http://www.cronica.com.mx/notas/2018/1070534.html

*2 Thanks to Juan Pablo Ramos for recommending this text. Paul B. Preciado, “The Ocaña We Deserve: Campceptualism, Sexual Insubordination, and Performative Politics,” in Stedelijk Studies 3 (2015): 1-41, 3. https://stedelijkstudies.com/journal/preciado-ocana-deserve/#_edn1

*3 Ibid, 5.

*4 Melodrama as a genre is characterized by the telling of stories based on domestic crises—a reflection of the national panorama—that would seek to condense all possible drama and suspense into a familial microcosm.

Published on August 6 2020