Review

Mired 'Landscapes' of Frustration: Ana Segovia, Mariel Vela, and Diego Vega Solorza

by Nicole Chaput

At Galería Karen Huber

Reading time

8 min

I’ll be frank: Ana Segovia and Mariel Vela are among my dearest friends. I haven’t had the pleasure to meet Diego Vega Solorza personally. This text approaches Paisajes from a lens of closeness, which reveals some things while obstructing others. In addition to my friendship with Ana, he and I had an almost identical academic background, at the same university. I reflect on Paisajes (Landscapes) from painter to painter, contemplating Segovia’s pieces from the intersection between figuration within the frame and the writing in movement*1 of Diego Vega Solorza’s choreography. The encounter was boosted by the research of Mariel Vela. I’m interested in the tensions of figure and background within painting and how these are replicated in the logic of collaboration between those disciplines involved in this project.

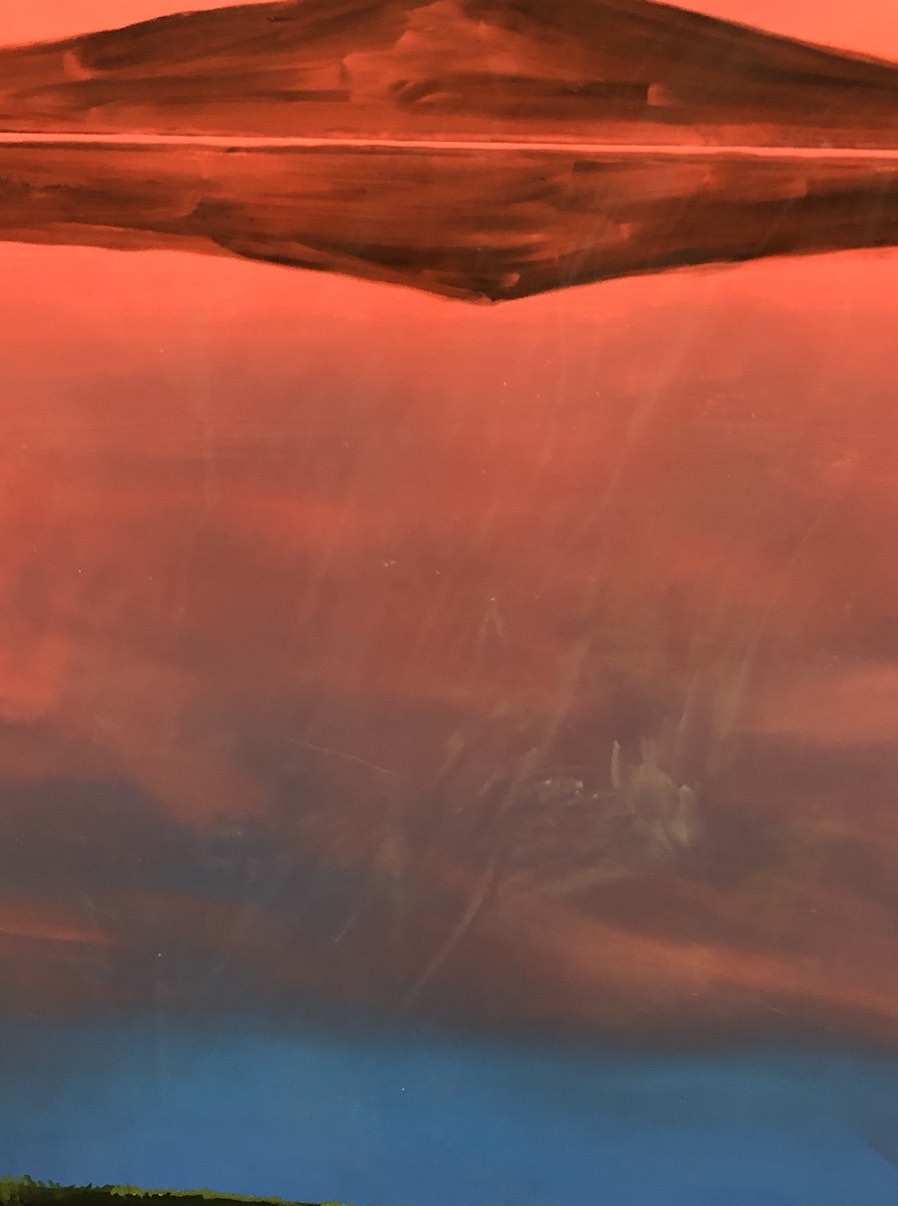

Nothing is as revealing as our own tastes. The value judgments accompanying them can have artistic license. When it comes to painting, frustration is a factor that weighs heavily with me. I’m interested in how the frustrations of the hand that paints and the eye that sees are archived within the surface of the pictorial frame, in close relation to the phenomenological energy of matter, which brings its own kinks. I enjoy when there is a space in which the author’s pretensions—whatever they may be—are hindered or affected by the stubbornness of the vehicle (the paint) and when this is made visible. My body responds to these affections. I find no evidence of processual struggle*2 in the execution and image construction in Segovia’s recent paintings. Despite this, my body responds to them for other reasons: the fluidity of his stroke, the sensation that the brush glides over the paint as if it were butter, or the luminosity that he creates when passing from his sepia bases to the vibrant palette that characterizes his production. Even so, where is the frustration in Ana Segovia’s work?

Based on his concern with representation inside the frame, Segovia facilitates an interdependence of expansive subjectivities outside it. In Paisajes, he articulates his frustration with heteronorms through a commitment to plurality, seeking a congruence between discourse and practice. We are aware of many of the complexities and problems of authorship that are rooted in patriarchal and colonial issues, which we have the responsibility to continue rethinking. The author as we know him is usually located in the head. It’s no coincidence that the dismantling of this thetic nature of the creative genius, in the second moment of Paisajes, takes place via a collaboration.

Dance is a medium that constantly displaces the head within the body, allowing all its parts to be felt, experienced, and sustained, without any need to name a limb or organ in chief. Mariel Vela has sustained the dialogue between painting and dance, creating an investigative architecture that observes internal image collecting as an engine capable of moving and upsetting both the body*3 and creativity. For a month and a half, Segovia and Vega Solorza held sessions with Vela, who guided and expanded the theoretical and referential constellation that sprang from common interests. Vela approaches the body with a basis in her writing practice—one that formulates images within the reader—as well as from the rigorous muscular awareness that she has developed in order to think through various choreographic practices.

In her research, she emphasizes the immobile pause of the Greek vases of the classical period, static oracles that would have us intuit the immediate past and the immediate future of each pose. Focused on the first half of the 20th century, modernity has been a central theme for the outcome of Paisajes. Greenberg*4 marks Manet and Cézanne as the first modern painters, since their paintings transparently declare their own two-dimensionality, thus sacrificing verisimilitude. This paves the way to a generous aspect of modernist painting: that it does not seek to cover up the private choreography of the body that pushes it.

The cogs in the machinery between figures and disciplines are what allow us to understand the frustration in Paisajes. The dance opens and closes with a charro dressed in a red hat, rendering his head and face as inaccessible territories. His shirt is left open in order to reveal a perfect six pack: one of several surfaces on which Paisajes impels us to deposit our desires. Like an archetype with legs, this two-dimensional character functions as a cutout of one of the figures in the paintings shown at the gallery’s Project Room*5. Like a key to a hotel room, this figure slides on the set to open and shut the collection of homoerotic scenes composing Paisajes.

The other dancers wear blue, echoing the water and sky of the landscape they inhabit. Red and blue behave as a duality whose intersection is situated in a pink sunset, a bleeding horizon. The first time I saw these costumes, they were at the back of the mural, designed by Carlota Coppel and Fernando Vega. The rearward curve that departs from the mural on the wall is accessorized with eleven taut steel cable strings, from which hang the blue costumes of nine dancers, designed by Arturo Lugo. Seeing that image, I thought of the long-sleeved indigo blue overalls that Ana wore when painting a few years ago. This could be a mere coincidence, but I resort to that memory in order to think of costume as a portal, allowing us to be double agents. It amuses me to think that Segovia would cross-dress while painting with those blue overalls.

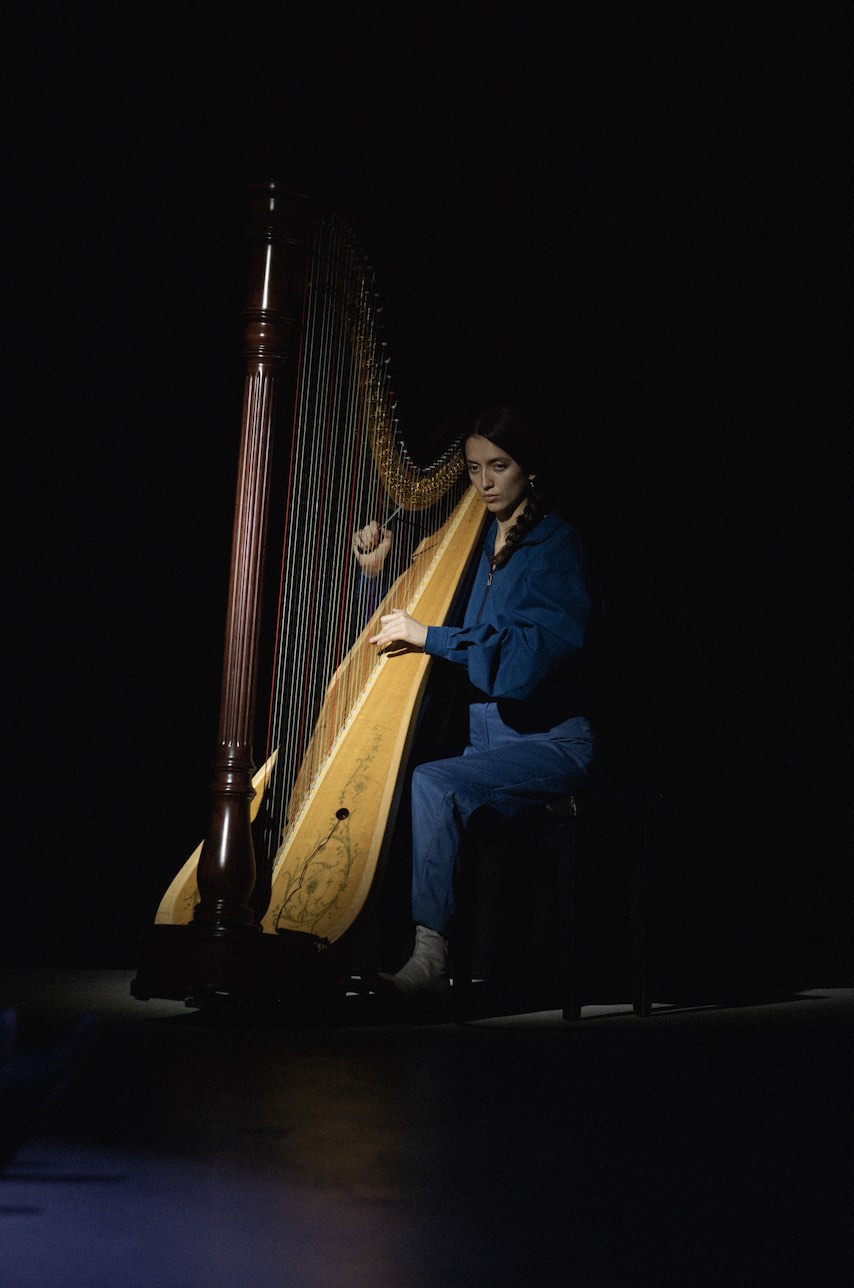

The harpist, Alondra Maynez, was also dressed in blue, like the dancers. Throughout Paisajes, Maynez moved about and experimented with various possibilities in terms of instrumental technique, improvising according to the rhythm marked by the dancer’s feet. The analogies of the harp, meant to emphasize the movement and emotional tone of the narrative, were expansive. Maynez used a metal screwdriver to accompany the introduction of the blue dancers. Operating as though it were a prosthesis, she had to extend her own body so that her instrument could translate the conceptual movement, avoiding the angelic connotation that usually accompanies the harp. I find it very symbolic that a screwdriver was the object chosen to intervene in the sound. I frequently hear the term “deconstructed” thrown around, an invocation that indicates a reflective work, aiming to eradicate heteropatriarchal codes. Perhaps the terms “disassemble” or “unscrew” would be more exhilarating.

At the climax of the choreography, the dancers undress and run towards the vanishing line of the mural, as though they were going to dive into the water or the sky. They land on the surface, smearing it with sweat and saliva. The bodies begin kissing each other, with some limbs stuck to the mural. The mural ceases to be a pictorial strategy and becomes the head of a bed or the misted glass where the traces of an erotic moment are printed, like the carriage in Titanic. This invented landscape contains an idyll where not only are nature and culture reconciled for a moment, but also where we witness the romance of a collaborative process. Traces of that multi-body’s sweat are registered on the work’s surface.

One of my great frustrations with painting is the violence of the picture frame: which portrays a slashed figure, incomplete. The body is inherently vulnerable to the way it is represented. In the choreography of Paisajes, the bodies are not delimited within a static composition; rather, the intimacy that the figures embody exposes them to the scrutiny of the viewer’s gaze. The lenses of our cell phones were blindfolded in order to protect the privacy of the dancers and control the way their bodies would be represented and reproduced. That precaution alerted me once again to the vigorous threat of violence that is inseparable from the act of looking, thus reiterating the frustration that I feel at the persistence of the framework that directs my eyes.

Paisajes can be viewed at Galería Karen Huber until November 5.*6

Translated to English by Byron Davies

1:André Lepecki, Exhausting Dance (Routledge, 2005).

2: Sedimentation of the oil paint or accumulated textures, pointing to changes in direction (as though the brush were a rudder), or transformations from one layer to another. These changes of track can be seen in Matisse’s paintings from 1916 to 1930, for example.

3: Giorgio Agamben, “Nymphs,” trans. Amanda Minervini, in Releasing the Image: From Literature to New Media, ed. Jacques Khalip and Robert Mitchell (Stanford University Press, 2011), 60-83.

4: How annoying it is to have to quote Clement Greenberg, but he is the scribe of modernist painting (as per his own agenda), for better and for worse. Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting” (1965) in Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology (Harper and Row, 1982).

5: Where we find six paintings by Ana Segovia mounted on a wooden scaffolding.

6: I would like to thank Othiana Roffiel, Bruno Enciso, and Israel Urmeer for accompanying me in the process of writing this piece. And thanks to Sandra Sánchez for the libidinal energy that she has given to her processes of editing.

Published on October 16 2022