Essay

How Do We Cur(at)e This Story?

by María Emilia Fernández

Reading time

8 min

How

to

tell

a

shattered story?

By

slowly

becoming

everybody.

No.

By slowly becoming everything.

Arundhati Roy*

I haven’t been to the museum in three months. Instead, I sit at my dining table, which also functions as a desk, in front of my computer, answering emails, reading, researching, and writing texts about works of art. I do practically the same as I did before, only now from home. My days go by making lists, checking boxes—whatever it takes to maintain a rather imaginary semblance of order and control. And , if I had to define the work I was doing before, if I had to condense it into a single word, I would say that I was planning. But the pandemic, which has temporarily closed the museum, has also brought with it a contagious uncertainty. At the curatorial level, the exhibition program has had to be reinvented several times in the last few weeks, and the plans, at least from now until 2022, are being made knowing that everything could change again in an instant.

To be frank, what governs my routine is not any pending task of the museum, but the soundscape created in my neighborhood: the sounds, space, and time that are connected much more intimately than I could have recognized before. I’m now acquainted with the complete inventory of clammer, voices, meows, and barks of the neighborhood in which I live. I know that it’s 9 AM because the neighbor across the street sings at the top of his lungs while walking his dogs; I know it’s already noon when the woman in the apartment upstairs steps out into the sun to talk about some bills; and I know it’s night when the couple living downstairs make love or argue loudly in Italian. Thus so I measure my day.

In any case, the rhythm of this new normality has opened a kind of parenthesis—a pause or a conjunction that goes on indefinitely, in which I wonder: “What use is curating at a time like this?” I have always believed that a curator is someone who recreates and reinterprets the chaos of history over and over again. Someone capable of making reality seem strange. At its best, this work shares something with the child’s outlook, an imagination that disrupts the normality of the world as we are acquainted with it. If we go to the most basic elements: curators tell stories; it’s just that by telling them they can tear away the veil of what, by force of habit or resignation, we have become accustomed to telling in a certain way.

Part of the magic lies in holding on to the story even while being inundated with the details of planning and management that curating involves: the lists of works, the gallery texts and information cards, the relationships with collectors and lending museums, the juggling of budgets, and the communication between the teams of an institution. But in the end I always return to the task of narrating, even if it is, as Valeria Luiselli writes in Lost Children Archive, “knowing that stories don't fix anything or save anyone but maybe make the world both more complex and more tolerable. And sometimes, just sometimes, more beautiful.”(*2)

What the pandemic has led me to question is not so much this essential task of narrating, but rather the language we use to tell these stories. I think of the words of the German artist and theorist, Hito Steyerl, about curatorial practices, and how “it is rather about creating unexpected articulations, which do not represent precarious modes of living or the social as such, but rather about presencing precarious, risky, at once bold and preposterous articulations of objects and their relations, which still could become models for future types of connection.”(*3) I am therefore preparing myself, in this confinement, to learn to listen to what things tell us, without trying to translate their language, taking note of what happens between an oxygen tank and an open window, between a lit lamp and a thermometer.

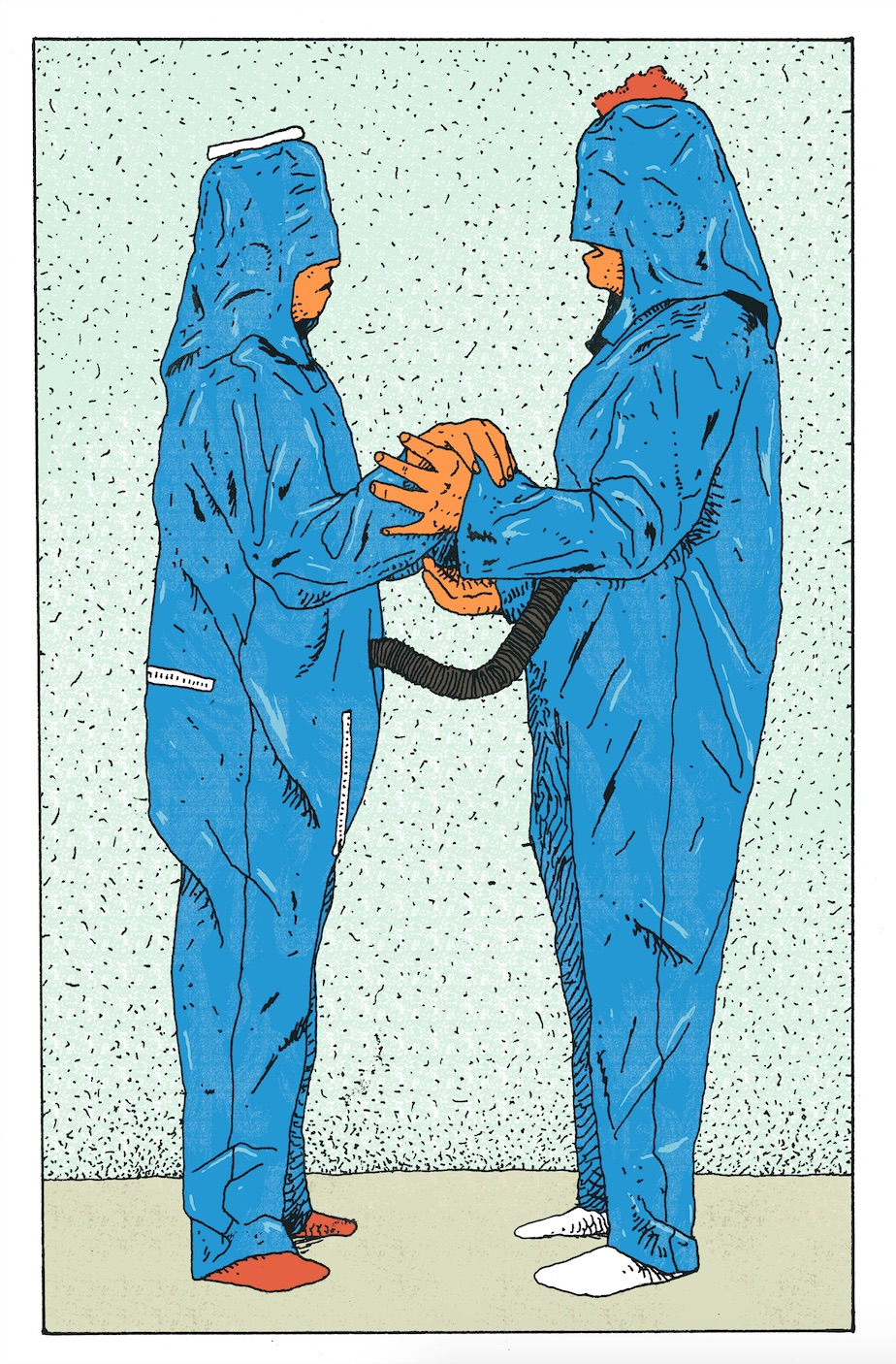

The threat of contagion has made tangible our vulnerability; not only as it relates to health but also understood as a search for closeness and as a surrender to other bodies, as a desire for intimacy. I re-read a text by the translator and researcher Irmgard Emmelhainz, a kind of letter where she suggests making peace with our bodies and their fragility, with pain and the fear of losing control.(*4) It is she who quotes the poem by Arundhati Roy accompanying me these days as two people close to me have been seriously ill. Their testimonies say that “it’s like going through places of the mind and body that you don’t know exist, dark places, hells, but then it passes and it’s as if again they don’t exist. They once again become inaccessible, unimaginable.”(*5) In the midst of those hells, “you hold on to the fear because there comes a point where it’s all you have left. It’s fear of the bug, but also of letting yourself go completely, and, yes, you feel like you’re leaving… So then, although you already feel better, you’re still afraid. It’s like your body doesn’t let loose the fear.”(*6) I listen to them and suspect that between the fever and the fatigue they ran into everything head-on, though they were able to return.

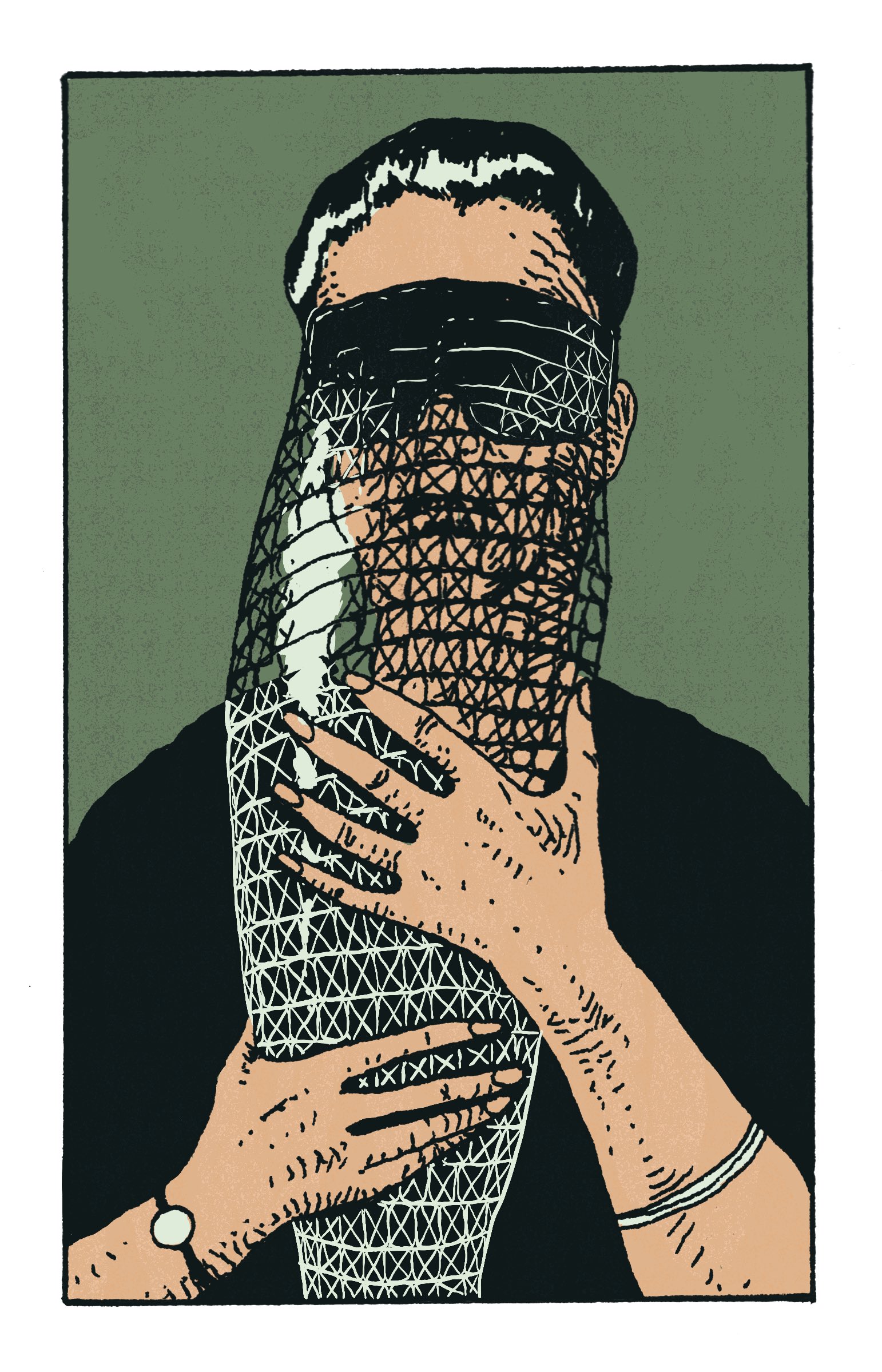

The two convalescing people I know are much more aware of their bodies, of each breath. The face covering has a similar effect. The masks and plastic face protectors I see when I go to the supermarket remind me of the ideas of Lygia Clark, whose sensory suits and masks offered to mute certain senses in order to over-stimulate others. Denying light to the eyes in order to put the ear on alert, or through touch finding a new way of approaching the other. The resemblance of these devices to the health precautions taken by medical personnel against Covid-19 is a mere coincidence, although the effect is very similar. As a curator, I wonder: “How many works of art have we not seen that seek to make the viewer more aware of their body in space?” I think of the human tissue articulated in Lygia Pape’s Divisor (“Divider”), an organism that would walk the streets and allow participants to feel the strength of the individual in the collective flow. How many installations and performances that did not invite us to feel, to smell, to turn to see ourselves seeing, without jeopardizing anyone’s well-being, without disturbing the hubris that accompanies health.

I follow the news and it’s clear to me that we are, at best, a bit broken. It’s no longer just the pandemic, which has turned into a macabre backdrop, but also the murder of George Floyd, slowly strangled by a cop who did not flinch at his pleas. That image continues to haunt me, out of the anger and chills it causes me. But other news also indicate that we are badly hurt, devastated: the death of Giovanni at the hands of a group of cops for not carrying a face mask, the global warming crisis, and the femicides that this country’s government insists on making invisible. All this for me confirms the diagnosis: we are tattered inside. And although the sounds of my neighborhood may have a palliative rhythm, beyond that what one hears is a fractured social body.

And what use is curating at such a time? It was my mother who recently asked me about the connection between “curar” as a synonym for healing and “curar” in the sense of planning exhibitions. At the time I ignored the comment and took the conversation elsewhere, but when she fell ill her question did nothing but gain strength. The more I turn it around in my mind the more I see how their meanings become closer, how they talk to each other. What if cur(at)ing was a way of making sense of our fragments? A way of organizing our wounds, of recording questioning voices, of healing through narrating disagreements. If what we have are scraps, how do we cur(at)e this story? (*7)

* Arundhati Roy. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. New York: Knopf, 2017. p. 442.

*2 Valeria Luiselli. Lost Children Archive. New York: Knopf, 2019. pp. 185-6.

*3 Hito Steyerl. “The Language of Things.” June 2006. https://transversal.at/transversal/0606/steyerl/en

*4 Irmgard Emmelhainz, “Shattering and Healing” in eflux, Journal #96 - January 2019. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/96/244461/shattering-and-healing/

*5 María Eugenia Nadurille, June 2020

*6 Juana Becerril, June 2020

*7 Translator’s note: Here and in the essay’s title the Spanish “curar” has been translated as “cur(a)te” and “cur(at)ing” in order to convey both senses of the former, which the author is relying upon and drawing attention to in this paragraph.

Published on June 26 2020