Review

The Ghost of Identity Produces Clowns | About an Exhibition by Juan Caloca

by Stefanía Acevedo

At Estudio Marte

Reading time

7 min

I had the opportunity to talk with Juan Caloca (Mexico, 1985) about his most recent exhibition Soy un extraño para Dios/ para la policía/ para mí mismo… y para mis amigos (“I’m a stranger to God/to the police/to myself …and to my friends”), at Estudio Marte. The gallery text, almost hidden, is a free translation by the artist of a poem by the British rapper Kate Tempest. One of its fragments states: “It’s coming to pass, my country’s falling apart / The whole thing’s becoming such a bumbling farce” (“Va a pasar / Mi país se cae a pedazos / Toda la cosa se cae a pedazos”). This reflects the current moment of uncertainty that, among other things, limits the number of people who can be in a closed space at the same time, but also opens the possibility of generating more intimate encounters among those who visit the show:

“To me, it seemed pertinent to be able to share this in these moments of anxiety and distancing and to put on this exhibition as a pretext for seeing my friends again,” says Caloca.

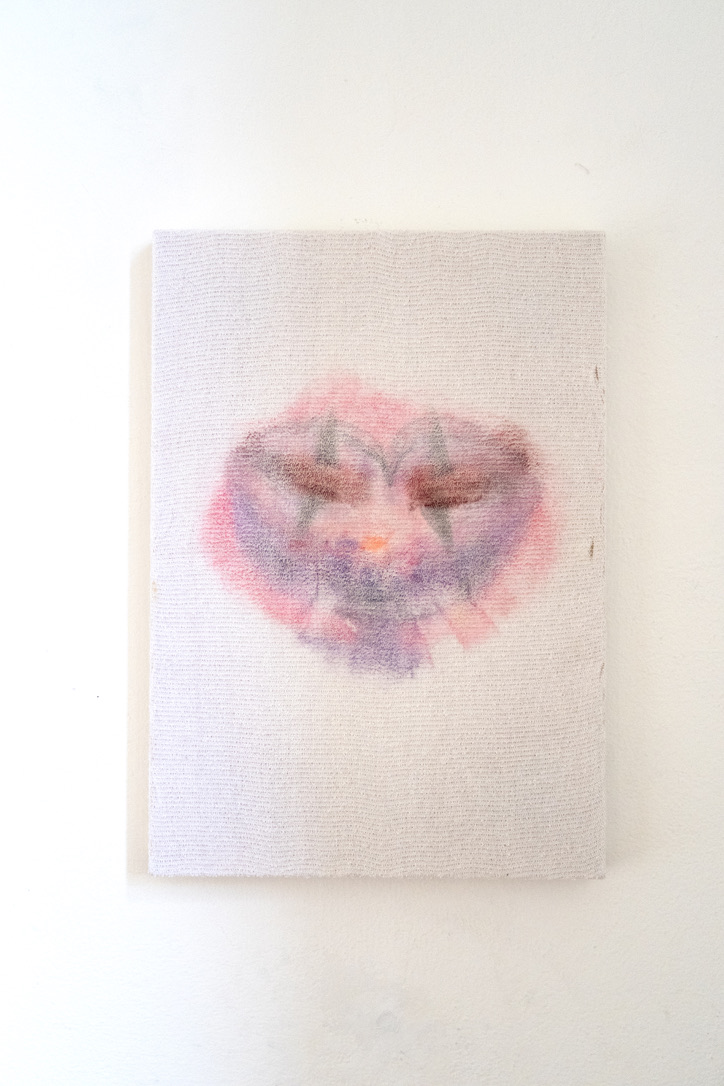

The show is made up of a series of fifteen prints, specifically “face prints,” that the artist has produced since 2018: “I arrive at these images through a performative process: I paint onto myself a clown face and then I make a stamp of it. Hence the decision to select a towel cloth as a support, which is the material used to remove the makeup…I call them faceprints.” His friends have sometimes participated in this process. The last fragment of the show’s title, “…and to my friends,” is, in fact, an addition, carried out as an intervention, that the artist made to a phrase by the infrarrealista poet Mario Santiago Papasquiaro. With this he takes account of those meetings in which, as Caloca describes them, he and his friends would get together, drink, paint each other, and generate this sort of print. In the exhibition we encounter some of them as ghosts or as identity-less traces.

The clown faces materialized in the fabrics presume a question posed by the artist about his own identity, presenting an estrangement from this liminal figure that, on the one hand, stands between comedy and entertainment, and on the other, demonstrates the capacity to be critical and uncomfortable from the ironic perspective whereby the makeup works as a pigment, the towel as a canvas, the body as a medium, and the art market as an audience waiting for the next gag:

“I wondered how to paint without being a painter, what painting means, and how I can paint out of my questions,” Caloca comments.

The curatorial accompaniment was also generated from conversations with friends of the artist, who was the one who made the final decisions about installation. There are no exhibition labels. His process is shared orally with visitors. While some pieces are framed and others only have stretchers, several of them are shown simply hanging, intentionally exposing the disconnected threads and making explicit an unfinished process.

The pieces are distributed across two rooms; in the main room we find what, for its rawness and incompleteness, is perhaps the most uncanny piece. No sooner can one distinguish a face by the green nose of the center and a beard that drains down until it reaches the bottom of the fabric. Other random spots accompany that face. The reference to a blanket bearing a materialized face invokes the imagery of sacred apparitions, but there’s nothing like that here; it’s just a clown.

The central pieces, however, are a series of four prints on differently colored towels. Some of the shades printed on them fade into the dark color of the fabric; others are sharper, though not for that any more delineated. We find in one corner, hidden by the shadow generated from a large window, three further faces next to the exhibition’s title and an expression of gratitude to the artist’s friends, both in tiny letters. The three pieces show us different ways of making up and creating clown faces. Before moving on to the next room, we find a print distinguished by its phosphorescent colors and more defined shapes; perhaps in this case the combination between the fabric’s color and the makeup is what manages to bring out this face that seems almost drawn-on.

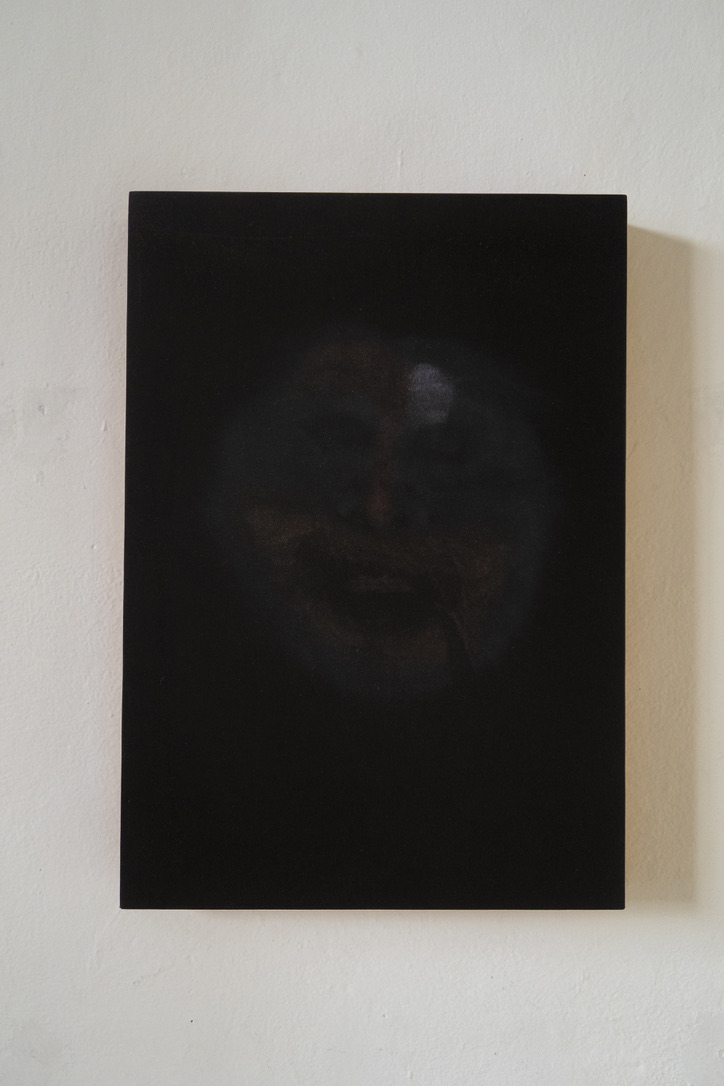

At the back, in the second room, there are some balloons, both flat and inflated, hanging from the ceiling and on the floor. They offer the sensation that we are late to a party and, with that, there arrives a kind of nostalgia or disappointment. Throughout his production, Caloca has been interested in accompanying his pieces with other objects, in order to generate tension between them and the visitor’s attention. The balloons accompany six pieces bearing somewhat more macabre prints than the previous ones. The print of what appears to be a smiling boy on a black fabric is perhaps the gloomiest piece; it’s especially difficult to hold the figure’s gaze. The details of this face are penetrating, making its presence the most phantasmagoric, as if we had reached the bottom of that blurred identity that runs throughout the entire exhibition. In a similar print, but this time on blue fabric, there’s a figure that looks like a screaming, severed head. The oil with which the fabric had been previously prepared for collecting makeup seems to have spread around the face, generating an invisible collar that could well be a shadow or a bloodstain.

As we advance through the exhibition, the anthropomorphic figure of the face fades and increasingly resembles stains or impressions that express the wear of a phenotype. A kind of covering and a mask with phosphorescent colors are stamped on the white surfaces of two pieces, further evoking clown faces. Finally, we are bid farewell by two pieces on gray fabric, one showing the minimal contours of a clown’s face, characterized by the pink and green of its makeup; while in the following piece one can’t even make out a face, but only the mark of something that has lost its shape.

I can’t help but mention the wispy spots and spray clouds randomly scattered across the gallery’s rooms and stairs, which generate a feeling of abandonment in the space, as if something had been left unfinished. They somehow echo the faceprints, which are also not very defined. By allowing the clowns’ makeup to continue up to the walls, the artist also questions the traditional format of painting limited to a canvas.

The pieces show different ways of inhabiting the clown, as someone who has a hard time holding their own countenance, and for this reason vanishes and must remove their makeup every time. Hence the question of identity runs across the surface of the face, leaving traces of an ever-changing corporality. Each piece is inhabited by a ghost that appears differently depending on who is looking at it. There’s something uncanny in these impressions, as well as something sad that manages to be generated from the balloons, stains, and faces: tonalities and unfinished images that invoke spectrality.

The gesture of maintaining some pieces without stretchers, or without a frame, as well as the use of ordinary materials such as towels, makeup, and party balloons—but especially the use of the face as a means of printing—accounts for a moment in Caloca’s work that keeps open both the question about identity and the ways in which it is manifest. His faceprints constitute an imprint repeated so many times that they make identity a spectrum that only manages to appear thanks to the deceit of makeup.

I keep wondering: “What does resemblance to a ghost mean?”

Almost just as we leave, Juan inflates a helium balloon and reads in a high-pitched voice: “I’m a stranger to God, to the police, to myself, and to my friends.”

The show is open, by appointment, until August 2.

Published on July 24 2020