Review

Cracking a Closed Object and Opening the Body of a Tree: Miguel Cinta Robles at N.A.S.A.L.

by Mariana Paniagua

Reading time

7 min

From the bark of the jonote tree —known as majé in the Chinantec language— a fiber is extracted that was traditionally used by the community to weave bags for carrying corn and squash harvests. These bags have since been replaced by plastic ones. Eligio Felipe Juan is one of the few people who still knows how to extract the fiber and use it for weaving. Miguel Cinta Robles approached him and his family —who live in Cerro Mirador— to learn the process.

Cerro Mirador is a small village located 15 kilometers from the municipality of San Juan Bautista Valle Nacional and 190 kilometers from the center of Oaxaca, where Miguel was born. It's also 180 kilometers from Tlalixtac, where he shares Terreno familiar, a project in which he and his family engage in agricultural practices and host gatherings and workshops.

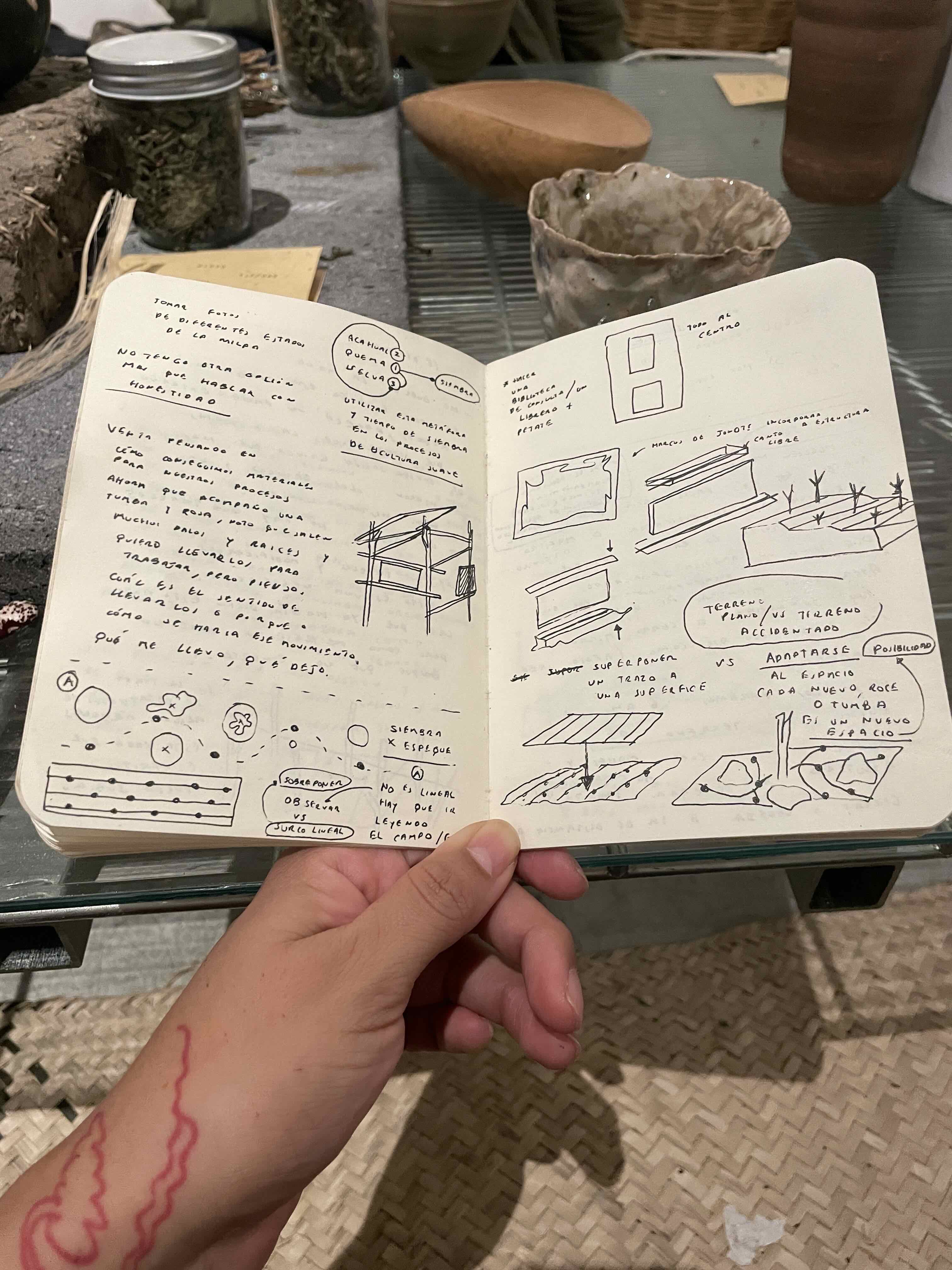

The first question that came to mind when I entered the gallery was: How do we deal with the suspicion of extractivism in contemporary art? Miguel shares this concern, which he addresses extensively in his travel journal¹, where he draws a problematic analogy to the journals used by conquerors when arriving in unknown territories.

As I entered, I was greeted by objects resembling those of an explorer: a woven bag, very low tables with notebooks, drawings, wooden figures, dyed fabrics, seeds, and branches. In the journal, he acknowledges himself as a stranger to the community, a topic he revisits multiple times. I found it thoughtful that he takes responsibility for his own gaze. Although the hierarchical structure of being both an artist and from the state capital is always present, Miguel prioritizes experience and his artistic practice as a multiplicity of actions rather than a straight line from a written project to an object. We can attempt to encircle, entangle, complicate, and unravel that line.

Is giving shape to something for artistic purposes different from giving shape to something for utilitarian purposes? For many reasons and relationships ranging from the poetic to the economic, yes, it is. But this exhibition suggests a close connection between everyday practices —like drinking a cup of tea—, working the land, and what we consider artistic practices, with all the problems this entails.

Living things move and transform, and interaction is something alive that generates ethics. It is through the porousness of the body that we can metabolize, narrate, or materialize it. The objects displayed here are like vestiges of these encounters.

The day I visited N.A.S.A.L., it was very cold. Miguel welcomed me, and after walking between the tables and walls, we sat on mats around a small table —also very low— on which there were two cacao seeds, notebooks, plants, jars with tea, and water being heated. He suggested choosing one of the ceramic cups —each was very unique— made by his friends to share hot tea. Besides sharing his experience with the exhibition process, we talked about friends, the weather, painting, art schools, and more. I appreciated that a show could be a friendly and open encounter, briefly stepping away from the typical relationship between a subject and an auratic object.

He showed me a small loom, the size of a hand, on which he was working, and mentioned that he thinks of the loom as writing, a warp that is discovered as you work on it. I believe that’s how practices and work unfold. Miguel presents the exhibition as a gathering, not just for the audience and the works but for those who participated in his learning process, his friends, the tree, his notebooks — all around a cup of tea. He says, "This one is for cramps."

I reflect on what a cycle is: of work, of production, the complex relationships that lie there, are activated, and lie again. Cinta Robles tells me he wants to compost the exhibition —I assume, the unsold pieces— so the material cycle would continue in some way. I wonder about the economic cycle of the show, but the thought passes. We participate in it, as in multiple practices and relationships. Part of the fiber of the tree splits into strands, disintegrates into multiple threads; in a small room, this is projected: an enlargement that looks microscopic. It strikes me as a beautiful gesture.

Miguel presents the exhibition from its margins. The breadth of all these practices extends beyond the gallery, ranging from slow, patient production to his attentiveness and hospitality in socializing this work within the art circuit. He writes in his journal about the objects he made with the tree’s wood and fiber:

Soft sculpture is the modulation of a solid over time. This change in material occurs through an act of sowing, care, accompaniment, and presence. To collaborate with a soft sculpture —or what would formally be understood as production or modeling— one must know how to care.

I think the softness he refers to also implies making visible the process of care involved in growing something. He tells me that when thinking about sculpture, he also draws on certain skills and attentions involved in agriculture, strategies that require a different temporality than industrial ones: a long-term effort.

I see the journal as the central piece of the exhibition. By traversing these vital processes and giving them a place within the artwork, the artist not only positions himself through artistic language or space but also exposes the intimacy of his experiences from an affective standpoint. I see the importance of that action in relation to the objects on display. Another significant gesture is the breakdown of disciplinary boundaries; the production isn’t categorized as sculpture, painting, or drawing but feels as though it was created from the possibilities offered by the tree itself. A tree nourishes and allows itself to be inhabited; in this case, it also dyed, was used for weaving and wooden figures, and witnessed the genealogy of its own body.

In terms of chronology, yes, there is a cause-and-effect process in the timeline of opening a tree, peeling it, using its fiber, dyes, and pulps, but the exhibition isn’t presented linearly. The tables display evidence like journals, sculptural pieces that seem to have been found on a walk through the forest, leaves, fibers, loose drawings, and dyed fabrics. Both the seed and the sculpture are present, collapsing the time of birth and instrumentalization.

The journal gathers the multiplicity of everything involved in producing an exhibition. Diagrams, anecdotes, and records of travel and dreams appear. The combination of journals and objects displayed on the tables seems changeable. It feels as though the tables are set up so visitors can work on their own narrative or poetics of the exhibition.

For a moment, I imagine these pieces as the product of a craft, like weaving a bag. I like that Cinta Robles opens space for that imagination. Even though the objects are artworks and are exhibited in the contemporary art market circuit, “I’m looking to escape effective communication,” he tells me.

A non-communicative art might be one where relationships aren’t predetermined, where they are mysterious or exist in another spectrum of language, one of multiple and shifting connections. This subtle murmuring between the dyes and the fabric’s weave without industrial sealer can only be interpreted within the system of relationships Miguel proposes.

I think of the story La autoría de las semillas de acacia [The Authorship of Acacia Seeds], which narrates the fiction of scholars studying non-human language and the mistake made when trying to understand the lexicon of plants by using a rapid camera:

(...) the art I was looking for, if it exists, is a non-communicative art, and probably not kinetic. It is possible that Time, the essential element, matrix, and measure of all known animals, does not enter into plant art at all. Plants may use the meter of eternity.²

“Materials raise questions,” Miguel tells me. I think they do, materials and processes raise questions, and perhaps we should attend to them without rushing to answer.

1: Available in pdf: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1IBqGrawMe1cfmBK2NSl6M2XlL6oNI-yx/view

2: Ursula K. Leguin, “La autoría de las semillas de acacia” in Ursula K. Leguin, Lo irreal y lo real, 1ª ed. (México: Minotauro, 2022), 636.

Published on October 18 2024