Review

"Una que cubre la palabra que la nombra": Luis Camnitzer at LABOR

by Jimena Cervantes

Reading time

5 min

Luis Camnitzer is one of the most recognized figures of Latin American conceptualism. His practice unfolds in a middle ground between linguistic critique—an inheritance of conceptual art—and a political sensibility shaped by the conditions of Latin American exile. Over more than six decades, he has developed an aesthetics that interrogates the ways power produces meaning and legitimizes reality. Within this context, LABOR presents Una que cubre la palabra que la nombra [One That Covers the Word That Names It], the artist’s first exhibition in a Mexican gallery since 1968.

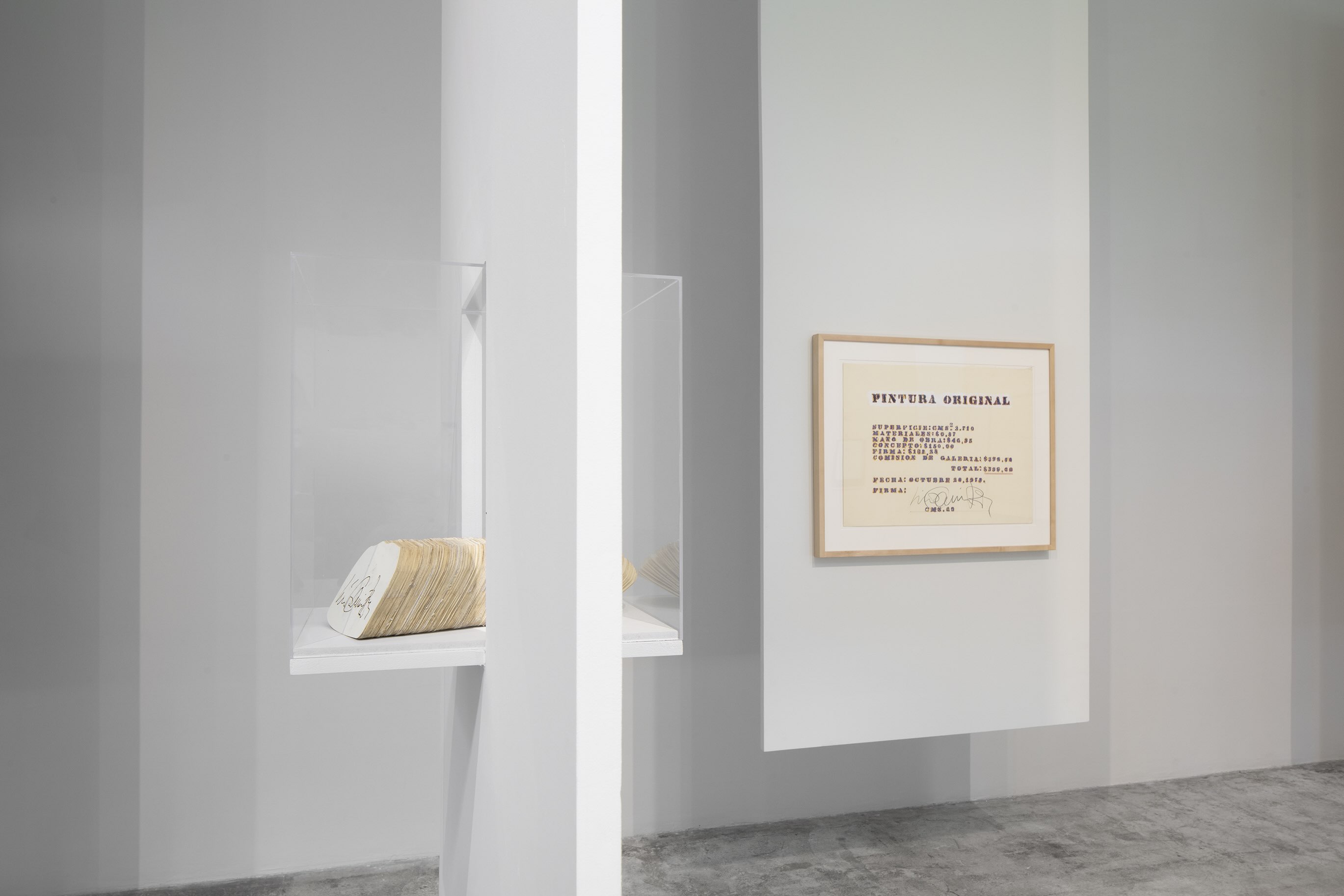

The curatorial layout is organized as a kind of retrospective presenting around sixteen works, including photographs, prints, and installations. The exhibition succeeds by suspending the pieces on a series of panels that allow the viewer to see both the front and the back of each work simultaneously. By proposing a display that departs from the logic of frontal contemplation, the exhibition destabilizes the single point of view and the visual hierarchy that traditionally structures the experience of art. Seeing the reverse side is equivalent to looking at the mechanism—the place where the work is held together and authenticated. Access to what is usually concealed reminds us that even the most dematerialized works retain a minimal materiality: their inscription within a system of validation.

For example, Object Boxes (1973–78) is a series of wooden boxes sealed with glass that incorporate, on their lower edge, a gold plate engraved with a statement that functions simultaneously as a title. Inside the box are minimal objects—fragments of materials, scraps of paper, color stains, traces of actions—that do not operate as illustrations of the statement but rather render it unstable. The slippage between word and thing enables the reconstruction of a relationship that is never fixed: there is no definition, example, or secure correspondence. In this clash between word and object, a metonymic process is activated in which each element points to another that remains absent. Within this series are works such as The Reason of Alchemy, Fragmento de vidrio o plástico sobre hoja de vidrio o plástico and Una que cubre la palabra que la nombra (1973–1976), the piece that gives the exhibition its title.

More than a poetic formulation, the phrase points to the intuition that every assertion that claims evidence contains, in some way, a strategy of persuasion—a fiction that organizes the perception of the world. The response, therefore, is not to oppose one truth with another, but to reveal the mechanisms through which that truth becomes instituted and acquires authority. This gesture can also be read in continuity with the logic of the reverse that runs through Camnitzer’s work and the museographic decisions that accompany its display.

On the other hand, we find pieces such as Pintura original(1973), which forms part of a group in which Camnitzer explores relations of power in art. Both in this work and in Signature by the Slice(1971/2007)—a paper sculpture composed of slice-shaped pieces, each laser-cut and marked with the artist’s signature—and Signature by the Inch (1971), a contract in which the artist offers his handwritten signature to be sold by linear inch, the conversion of the symbolic value of art into exchange value is explored in the most literal way possible.

Likewise, in works such as Flag (2021), Camnitzer performs an analogous operation on a symbolic and conceptual level. By replacing the stars on the flag with a banana, the artist exposes the reverse side of U.S. democratic rhetoric, reminding us that every official image conceals the web of exploitation and colonialism that sustains it. This juxtaposition of elements not only fractures the hegemonic narrative but also acts as a gesture of unmasking, revealing what the official image hides: the extractivist, racialized, and violent substrate upon which the rhetoric of American progress is built. While the flag is commonly associated with ideals of freedom and democracy, the banana introduces a historical resonance by evoking the notion of the “banana republic,” an expression coined in the early twentieth century to describe the Central American countries whose political and economic life was subordinated to the interests of large foreign corporations, especially the United Fruit Company. Camnitzer shows that “this is not a flag,” but a system of domination naturalized as a national symbol.

In the face of the contemporary rise of the far right and global authoritarian tendencies, it is pertinent to return to Camnitzer’s work and the reflections it opens. Today, in a context in which “Latin America” continues to function as a totalizing category—a geopolitical invention rather than a shared identity—his work distrusts any form of representation that fixes the Latin American as a style or as a marker of exotic difference; instead, it interrogates the languages that produce that difference. It is not only a matter of doubting what one sees, but doubting why one sees it in that way. In a field where the work is not limited to being contemplated but demands critical participation, the need emerges to rethink the relations between art and pedagogy, as well as to recognize that passive spectators do not exist—that even apparent inaction constitutes a mode of interaction.

Although these questions open much-needed conversations, the exhibition also reveals the structural tensions that have accompanied conceptual strategies since their beginnings—namely, the impossibility of escaping the material conditions of their production. Their educational power is mediated by structures of class, access, and institutional legitimization. While Camnitzer conceives of art as a cognitive and emancipatory tool, he recognizes that its critical potential is inevitably mediated by these conditions. Therefore, it is essential to activate critical imaginaries that make visible and contextualize the conditions that determine its own circulation. And if those of us who practice criticism are unable to situate these conditions, that emancipatory potential risks remaining a privilege, limiting its transformative reach.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

Published on December 1 2025