Review

Material exercises | Aire by Manuela García

by Alan Sierra

At Plomo Gallery

Reading time

4 min

“To turn the inside out without using a knife” is the opening invitation of the poem Ejercicios materiales (“Material Exercises") by the Peruvian writer Blanca Varela. Through simple instructions, the poem thematizes spiritual disciplines, while also presenting an attitude to be reiterated throughout the text: a willingness to stretch plastically the boundaries of words, allowing bodily and poetic spaces to run together. The question to follow the opening exercise would be, How is one to go without using a knife? Next, it would seem logical to add: How is one to let form be determined by a work’s internal logic?

In the large window connecting the exhibition space to the street hangs a ladder made only of rope. More than a ladder, it appears to be a mass of knots, a fabric. The sculpture invites one to enter the gallery using one’s physical strength and balance, faculties that will steer the visitor in the mental process necessary for assimilating Manuela García’s work. If one is particularly clumsy and manages to miss the hint, one should nevertheless not lose sight of the fact that the exhibition seeks to transmit knowledge that can only emerge when bodily and mental experiences interlock.

The way that Manuela approaches creation is complex, its synthesis seeming to come from the direct observation of materials in their private nature, in testing grounds far from society and its interruptions; however, her work is deeply human, strongly linked to the perceptual apparatus, part of a constant meditation on the body of the artist as well as that of others. From where else would originate such solutions as coloring textiles using only dust, or knitting without warp?

It is very fortunate that the works the artist has prepared for this exhibition are properly installed. Their assurance consists in having been correctly fitted: from their relations with the space’s ceilings and walls to the good balance of their appearance, function, and maintenance conditions. Some, such as Círculo or the series Arcos, produce subtle orbits out of the tension with which they have been integrated.

In the text Work with Material, Anni Albers mentions that the process of “giving form” is so divided into steps that only rarely does one get involved in the entire process of manufacture and, in most cases, one only knows the final product: “if we want to get from materials the sense of directness, the adventure of being close to the stuff the world is made of, we have to go back to the material itself, to its original state, and from there on partake in its stages of change.”

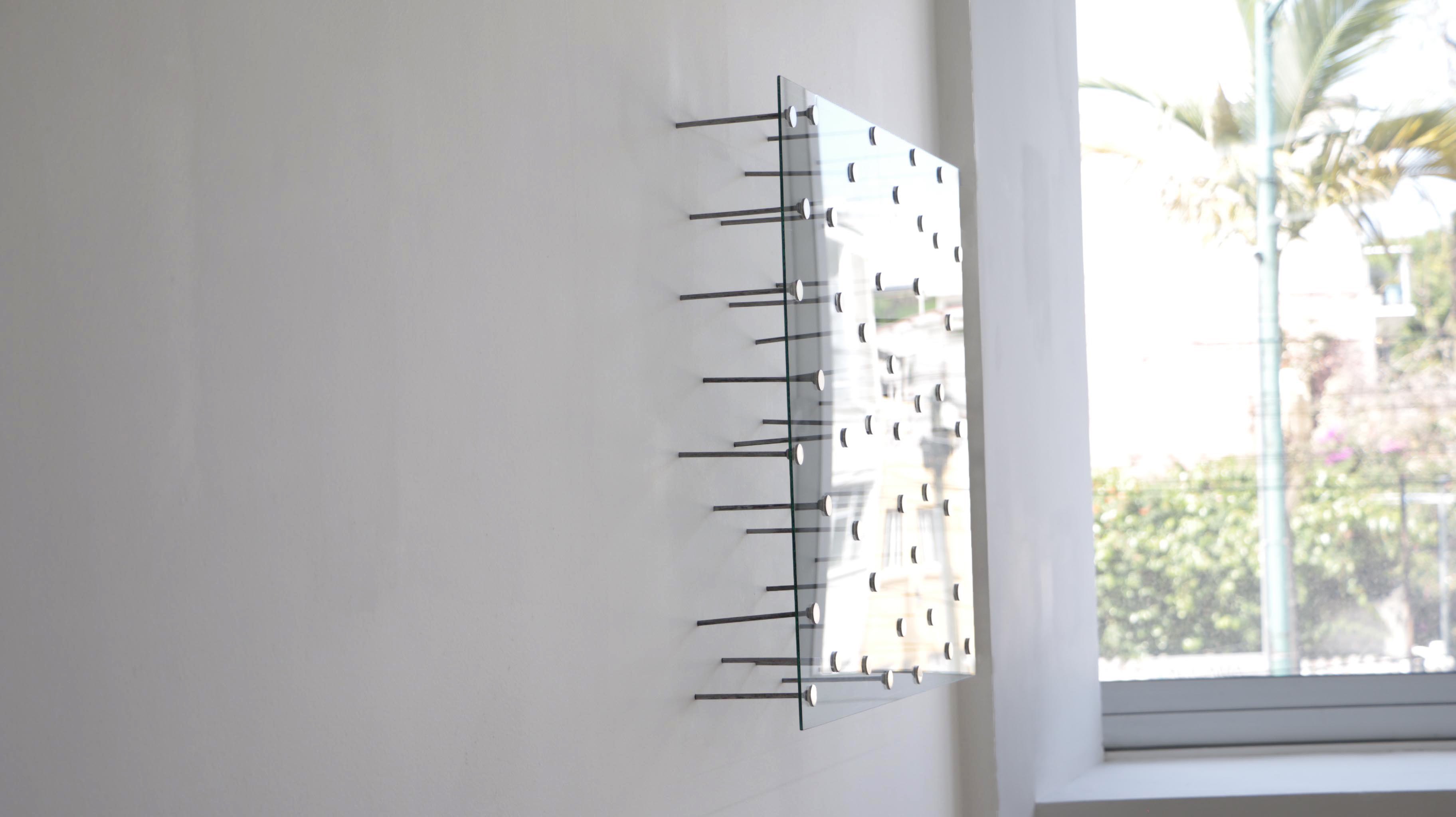

One piece that participates in this understanding is Superficie, consisting of a glass plate held by neodymium magnets to a series of nails on the wall. Superficie does not require an external reference to be read; for as long as it is sustained it will be able to boast a life expectancy. The artist installed the object personally, using her body to accomplish it; she says that she never knows in advance how this will work, but that at the moment the work remains still, art is happening.

Regarding her media and its economy, it has been important for Manuela to say less and less. Ironically, her work forces her to replace traditional words of sculpture such as “destroy,” “model,” and “assemble” with “cover,” “adjust,” and “balance.”

It is true that her works can be understood to occupy the midpoint between experiment and prank. For Obsidiana, from the series Piedras Preciosas (“Precious Stones”), she covered paper with tape so that it now appears to be a solid and especially heavy rock. The artist spoke of this during the installation, while looking for a suitable place to put the piece, upon being asked if she needed help carrying it. In situations like that the logic of the trompe l’oeil sneaks in and demonstrates its force. I can only imagine Manuela’s joy in verifying her mental powers, discovering that what she intuited was indeed true: the work that she imprinted upon the object now gives it weight in the eyes of the visitor. It seems necessary to insist that her works are completed at the instant of the joke, at the moment of verification.

Manuela García has devised a set of pieces that seem to undergo a physics of deception, drawing on much intelligence to pull off a trick that—after provoking laughter—sows knowledge of one’s surroundings. In her works the present is invited, in that her works are happening, in that physical and mental forces keep them together and give them a sense of unity, just as with our bodies in this very moment.

Published on September 20 2019