Review

When Opposites Attract: Jardín by Natalia Ramos

by Verana Codina

At guadalajara90210

Reading time

4 min

Jardín is a solo exhibition of work by the visual artist and illustrator Natalia Ramos. It’s also the second show presented by guadalajara 90210 at its new venue, in Mexico City.

Located on a quiet street in Colonia Escandón, the site consists of a first floor dedicated to the exhibition space, a second floor accommodating the project founders’ home, and, finally, a small terrace located on the third floor.

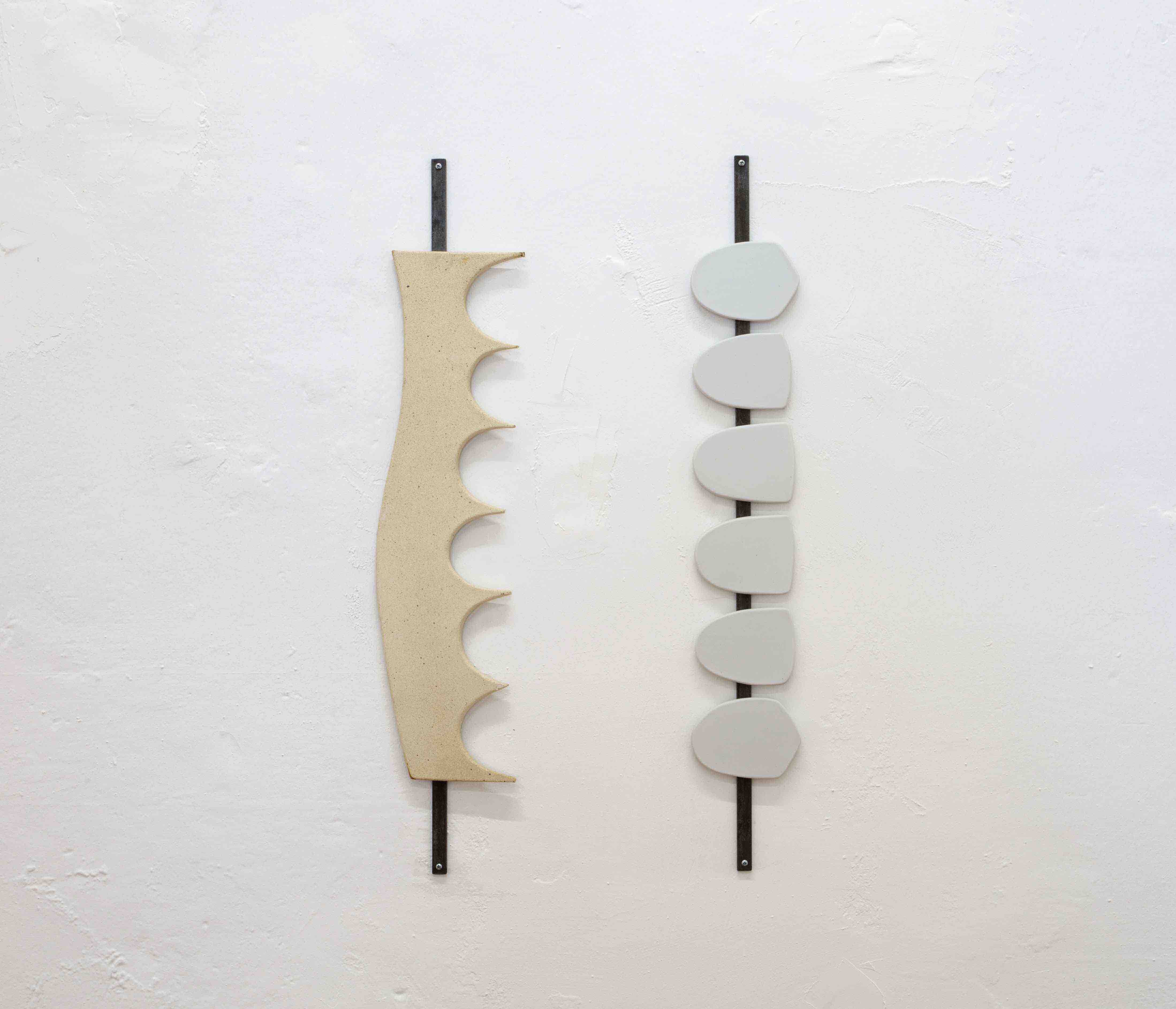

From outside, one can spy some of the pieces peering out through the house’s open windows. The bars of the grating intermingle with the sculptures’ steel structures—what Natalia refers to as “futuristic flowers”—ensuring that, even before one has entered the show, such opposites as exterior and interior meet.

Between leaps and bounds from one discipline to another, from resistant to fragile material, from the rigidity or the organicity of figures, we gradually discover that what appear to be oppositions are in fact complements. Antagonisms continue manifesting themselves in order to prove that opposites do not always repel.

Natalia mainly dedicates herself to editorial illustration, though she began experimenting with clay three years ago when her mother set up a ceramics studio in Guadalajara.

Although it’s clear to the artist that ceramics and illustration are contrary practices, she nevertheless thinks of herself as having managed to strike a balance in which one discipline feeds on the other, and vice versa. In this transfer, the two-dimensional and the volumetric do not form a contrast but rather coincide.

The set of works in Jardín is the result of this coincidence, which can be divided into five series. In the first room coexist the Ensambles pajarracos (“Bird Assemblages”), Mobil 01, the Flores (“Flowers”), and the Nubes (“Clouds”), while in the second room one finds a set of magnets, and, in the third, the Ensambles plantas (“Plant Assemblages”).

Working in another area—one with greater expressive freedom—has allowed the artist to expand her field of subjectivity, as it is not conditioned by editorial strictures to which she must adhere. At the end of the day, in an editorial environment, illustration must communicate a clear message, one that is often only achieved through the figurative. Figuration is to illustration what abstraction is to ceramics. Nevertheless, if we face both productions we find that, though far apart, their correspondence is indisputable: the objects’ figures—or abstractions—function as a kind of iconographic synthesis of her graphic practice.

There are three types of Ensambles (“assemblages”) in the exhibition: Ensambles plantas (“Plant Assemblages”), Ensambles pajarracos (“Bird Assemblages”), and Ensambles humanos (“Human Assemblages”). On occasion, Natalia refers to the group as Aspiraciones corpóreas del mundo plano (“Corporeal Aspirations of the Flat World”): figures that aspire to abandon paper’s flatness, to renounce two-dimensionality, as they seek to take on a shape, a body.

Once corporeality is granted to them, the abstractions are erected—they are assembled. Thus emerge pieces that finish taking shape when they begin to inhabit a space.

It’s curious how the idea of assemblage traverses through the work in two moments. Not only does it occur upon Natalia’s manipulating and interlacing the sculptures’ parts once they are out of the kiln. Natalia also plays with the assemblage in its material configuration. For the artist, her pieces are “a play of assemblages and dirt;” but I would say that they are assemblages of dirt. From the beginning, she mixes together such materials as porcelain, smoked porcelain, and different types of clay, in this case coming from Zacatecas and Tapalpa.

Dirt clouds? Steel flowers? Porcelain teeth? In this garden there is a convergence between images, materials, processes, and disciplines that, when face-to-face, do not rival each other, but rather harmonize. What seems to be a contrast becomes a coincidence. For me it’s clear: there are opposites that attract.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on March 18 2021