Interview

On Destruction: An Interview with Camila Arroyo and Ricardo Daniel

by Sofía Ortiz

Reading time

6 min

Camila Arroyo and Ricardo Daniel’s home is bright and cream-colored. Their shelves are packed with books and a few pieces of pottery. Out back, the patio is mostly empty except for a low table made of pallets set on concrete bricks. It's a Sunday afternoon, and they greet me with olives and beers. As we talk, vivid memories of their latest piece, Partirse en dos (Split in Two), start resurfacing. The work was presented at Obrera Centro during art week, produced in collaboration with Galería Gotxikoa and Sabrina Ol. My memories come in fragments: I watched the piece through gaps between heads, shoulders, and ears, since the venue was packed. “People we didn’t even know,” they told me later, a bit proud.

The space featured two long L-shaped structures made of dark gray painted paper, running up the walls and stretching along the floor like parallel tracks. “We spent a week on our studio’s patio, experimenting with different materials. We even tried soaking ourselves so the water could become part of the work,” says Cam. Rich adds, “We did some painting experiments, worked with pastels... and from all those ideas, something simpler started to take shape. At the same time, we were developing the choreography. We wanted a set design that wouldn’t just limit our movement, but could also serve as a record of the action itself.”

Instead of music, they danced to the rhythm of a dense, chaotic, and expansive text they wrote together, read aloud by different AI-generated voices. “We were looking for ways to apply the tools we use in dance improvisation and composition to other mediums, like writing,” Cam explains.

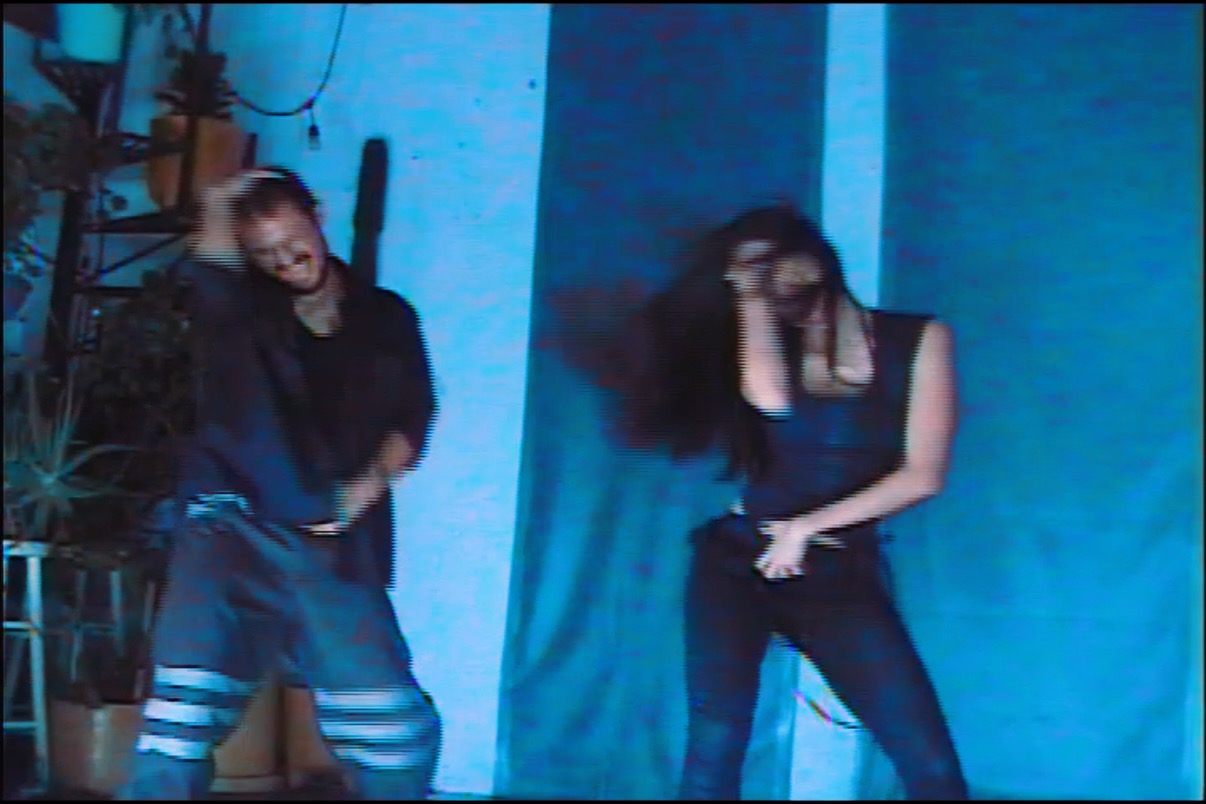

Within their parallel lanes, Cam and Rich moved together and apart, syncing up and falling out of sync. Sometimes they lay down; sometimes one would approach as the other pulled away. Sometimes they simply stood still, while the AI narrator’s voice filled the space. There were moments of flowing dance, others of repetitive, mechanical gestures. Their movements were sharp and eclectic: at times evoking the ‘choose your player’ screens of old video games, other times a ballet arm curve. A quick quebradita, a sharp heel click.

And maybe that’s what makes me fangirl over them: watching them together is seeing two distinct styles merge into something entirely new. They remind me of Rilke’s quote: a good marriage is one where each partner appoints the other as the guardian of their solitude. Rich, from Monterrey, moves like a dusty, distorted landscape, like hot concrete—a pop, like a beer cracked open with a lighter. Cam, with her ballet background, is long and precise. She’s finishing a PhD in Performance Studies and has thick black hair. During our talk, I notice her sandal-clad foot naturally flexed into a perfect point.

“One thing I love about working with Rich is how different we are. I have a softer energy, and he pushes me to climb into a different energetic channel—both in movement and in thinking,” says Cam. “As we’ve worked together, and as a couple, we’ve grown more demanding of each other. Getting more stubborn has made the work better.”

That push-and-pull is also present in the creation of the text that accompanies Partirse en dos. “We used the same improvisation strategies we use in dance for writing. It was convulsive, rhythmic, repetitive writing where we could steal, complement, repeat,” says Cam. “We became obsessed with the idea of what an instruction means to us, and that fed into the text too.”

Seeing the piece live felt like a rush: a battery of words and phrases—familiar yet sharp—referencing the north, NAFTA, explosions, followers, mushroom soups from Tres Marías, Gaza, Zipolite’s American tourists, Blink-182, the o-e-i-a jingle from Clight commercials, the decentralization of authorship, a girl opening a bag of Chips Fuego at the afterparty, and the missing people.

“We're always moving in service of the text. It's a bombardment of details—it doesn’t need anything else. Just us, two strips, and that's it,” says Cam. “I was a little sad that no one recognized it was Belinda,” Rich confesses, referring to the AI voiceover.

“It’s like scrolling,” I think. “It’s like scrolling,” says Rich.

The starting point for the piece was a prompt for a performance event: destruction. From there came the nods to video games as spaces for fantastical destructive possibilities. But the work expanded. “What else is destruction beyond kablam boom?” Cam says. “Starting from video games led us back to our childhood world—'90s pop culture. I remember those public service announcements on Channel 5 between Sailor Moon and Knights of the Zodiac, showing missing people. There’s nothing closer to destruction than that.”

“The piece is about separation,” says Rich. “The space itself is designed to prevent interaction between the two sides.”

“There are a lot of Mexican references, but it’s not an easily identifiable Mexican-ness,” Cam points out. “It’s not the kind of piece a foreign curator could just take back from a festival like, ‘I found someone in Mexico making amazing art.’ It’s contextualized Mexican-ness—not a transportable aesthetic.” Rich adds, “A lot of what we’ve produced in the last five years has had a strong localist stance, and I want to keep that. I think it’s cool to make more opaque, regional pieces.”

To me, the text offers a way to subvert globalization by steering it back into specificity. The Thundercats came from the U.S., sure, but Thundercats sliced between Clight commercials and “breathe, count to ten” PSAs—that’s recontextualized.

Partirse en dos captures the Mexico of my 2000s adolescence while also touching on the rise of digital nomadism and the far right—the cutting edge of contemporary life. It feels like a black hole, a vortex where two time-spaces touch: imagine the classic example of folding a napkin that represents linear time so that both sides meet. The text is the matrix that binds all the fragments together into a new whole, curated with rigorous pop instincts and well-trained bodies.

I ask them about that "something" that happens when they work together—something greater than the sum of its parts. “A new direction, a new color we’re building together,” says Rich.

“It’s about letting yourself be permeated by the other and becoming aware of your own weak points. The other becomes a new point of leverage,” Cam adds.

They can’t name it completely—maybe trust, maybe love—and maybe the only way to really understand is to go see their work. “The piece is alive, it’s going to keep generating,” Rich says. “Invite us to perform it!” Cam laughs.

Tanslated to English by Luis Sokol

Published on May 10 2025