Essay

Eleven Years of Painting in Mexico City at Galería Karen Huber

by Sandra Sánchez

Reading time

6 min

A decade ago, contemporary painting in Mexico City was like that awkward relative who shows up to a family dinner uninvited. Today, it’s hardly a novelty—sometimes it astonishes, other times it goes unnoticed, and at moments it’s even a little boring. Todo este tiempo, toda esta pintura: 11 años de la Galería Karen Huber [All this time, all this painting: 11 Years of Galería Karen Huber] is both a celebration and an exhibition that charts a transition—the shift from painting as the ghostly enemy of contemporary art to painting as simply another medium.

From the beginning (when, alongside Karen Huber, the work of Andrea Bustillos Duhart as operations director was crucial in shaping the gallery’s ethos) to the present, the gallery has played a significant role in the cultural ecosystem by openly declaring its intention to show, sell, and discuss painting—the last one through its HANGOUTS program.

Several exhibitions introduced something for the first time—not because they unveiled a novelty per se, but because the local scene kept experimenting with other ways of approaching the pictorial. This experimentation reached its peak with Paisajes II [Landscapes II] (September 2022) by Ana Segovia, where muralism returned as a portable stage for a choreography by Diego Vega Solorza (Ana and Diego collaborated with researcher Mariel Vela). In this piece, the dancers used the painting to critique the Mexican macho; they even sweated onto the mural’s surface, transforming it from background into an element among elements.

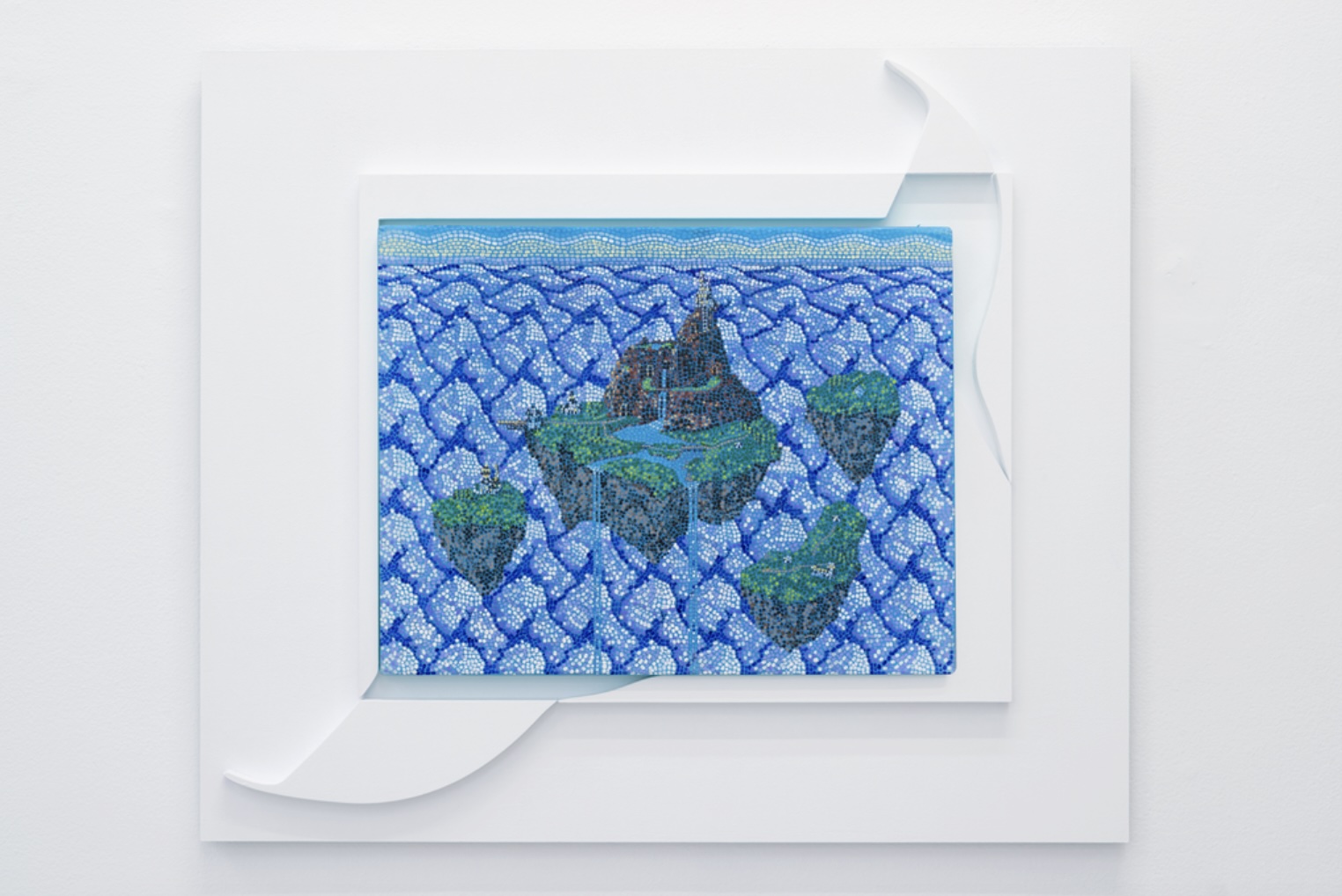

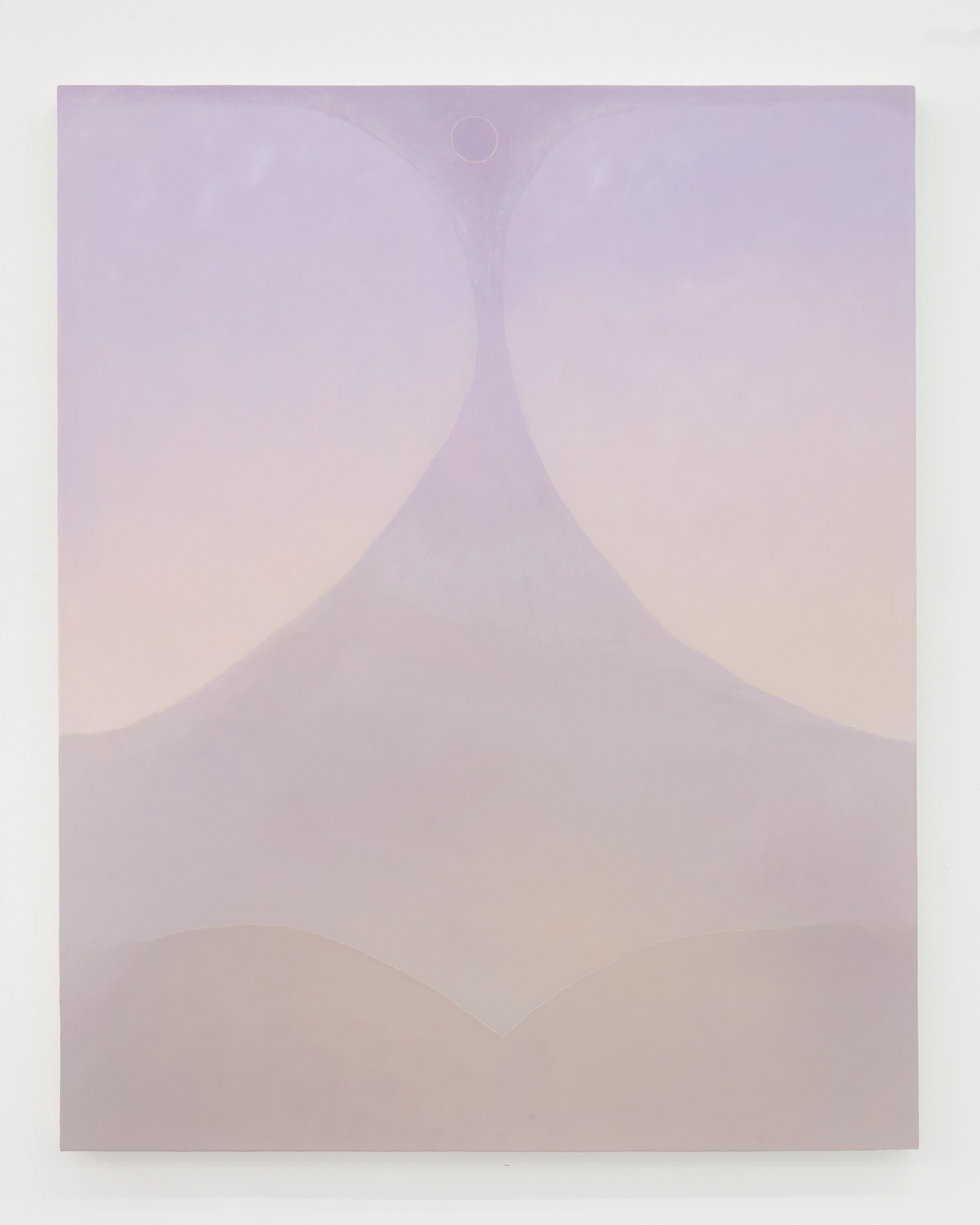

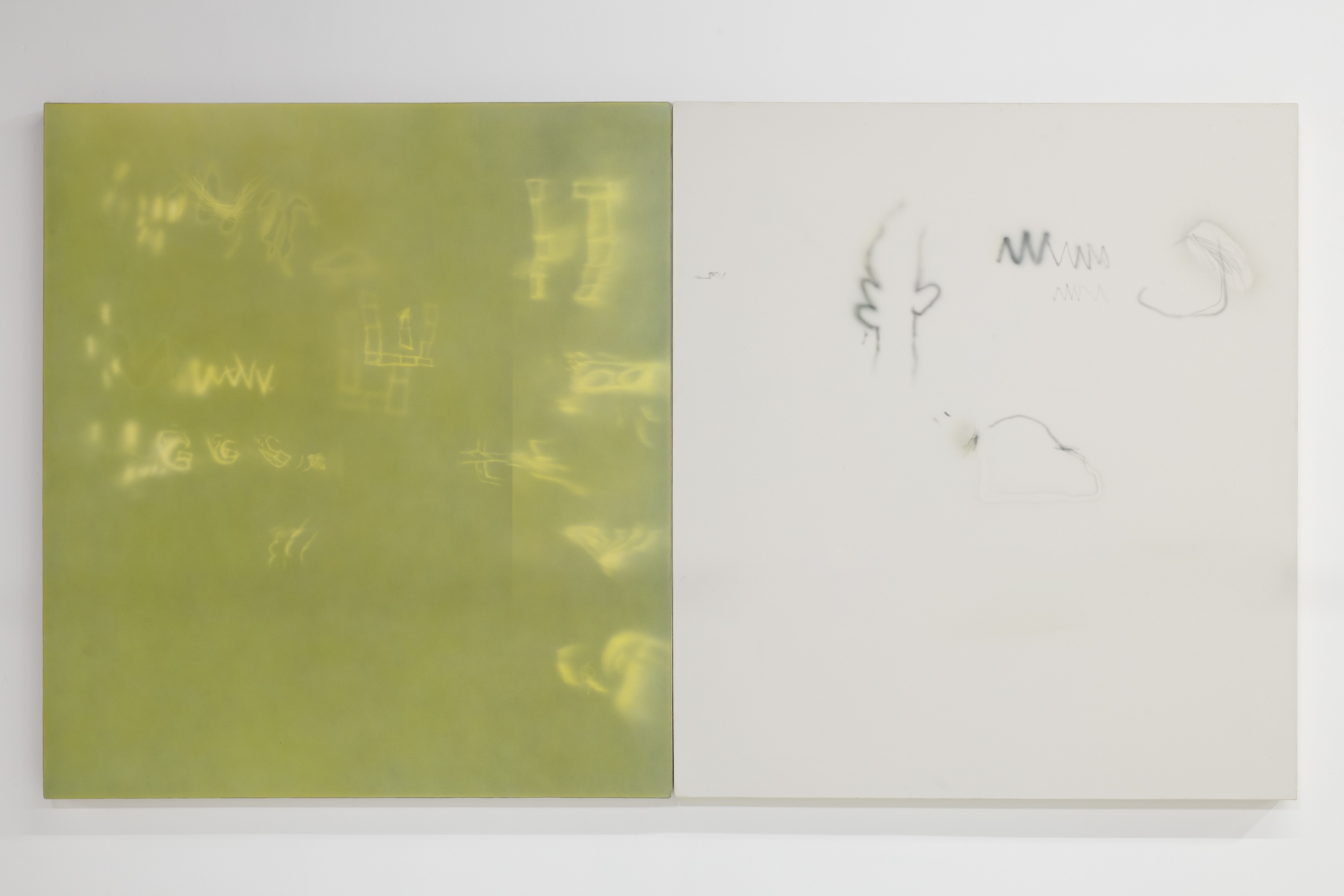

Karen Huber, together with Lulu (2013–2023), Oficina de Arte, Fuego, and El Cuarto de los Ojos Sucios, were among the first spaces—sustained by the same community beyond their founders—where painting emerged free from nationalist frameworks. During this period, there was no single unifying approach; instead, painting was treated as an open practice of experimentation and multiplicity: gender-critical paintings, self-theorizing paintings, vibrational paintings, political paintings, conceptual paintings, choreographic paintings, beautiful paintings—and ugly ones too, intentionally or not—paintings of flowers, plants, and assemblages. Paintings that jumped on the hype of the moment, that were solipsistic, self-referential gestures. Figurative paintings that didn’t seek to reflect reality, but to heighten, speculate on, or displace it. Paintings as philosophical essays. Painting everywhere.

In Todo este tiempo, toda esta pintura… the work of 34 artists is presented—those represented by the gallery, those who have participated in exhibitions, and those who have become part of the broader history of contemporary painting. The sheer diversity of pictorial approaches reflects what has taken place over the last decade. At first, it wasn’t easy: reaching the point of celebrating this exhibition at Karen Huber required enormous collective effort (often unpaid) among artists, curators, writers, teachers, cultural workers, and enthusiasts.

The scene reconfigured itself when painters stopped feeling ashamed for wanting to paint—for not being Francis Alÿs or Gabriel Orozco. Practicing painting once meant being dismissed within contemporary art circles. Faced with that crisis, an organic process of self-organization took place, leading to the creation of exhibition and discussion spaces where painting could be thought—not to justify its existence through arguments, but to talk about it, and in listening to one another, to trace what painting entails. I remember long, delirious conversations among Lucía Vidales, Christian Camacho, Eric Valencia, Roberto Carrillo, Allan Villavicencio, Verónica Vape, Marisol Plara, Cecilia Barreto, Xuty, and others, where we debated whether painting was or wasn’t a project; whether Philip Guston—in his writings—had already resolved the dilemma between figure and gesture; whether the surface was not a site of contemplation but the visible layer of multiple strata. How Derrida’s critique of phenomenological presence helped us propose the pictorial not just as what is visible to the eye, but as a realm of hauntings and survivals (Aby Warburg) that render paintings a plane of expression (Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari). We were happy.

The conversation continues. Today, for instance, we recognize that importing the abstraction–figurationbinary is insufficient to describe our practices. Or that the pictorial material itself is a medium of expression that doesn’t need—though it’s not opposed to—curatorial or academic validation to say what it has to say. We still find it endearing when certain curators see discourse before painting—unable to open their bodies and perception to the pictorial and to the singularity of the medium. Curators who can’t see art without turning the experience into a fetish of their own knowledge.

It is also a celebration to witness, through various mutations, the way each artist’s expressive language takes shape. In Lucía Vidales, color not only describes form but produces a visual and momentary explosion. In Christian Camacho, the introduction of Byzantine light into characters from today’s speculative imagination. In Eric Valencia, color that rejects ocularcentrism, deliriously updates the baroque fold, and leads to the haptic. In Merike Estna, the unapologetic mark on canvas. In Othiana Roffiel, membranes between forms—allegories, no longer symbols. In Jerónimo Rüedi, the medium that sustains both gesture and language itself, a substance that singularizes enunciation (signifiance, as Julia Kristeva would say).

Amid this celebration, it remains essential to insist on our own desires, problems, discussions, and aspirations within painting. We must stay cautious in the face of the medium’s proliferation, which often risks becoming what some accuse it of being: a canvas projecting ego, a proper name, a cliché. If contemporary painting in Mexico City is relevant today, it’s because it has opened—and continues to open—questions about its own genealogy, and about what is current, urgent, and yet to be conjured.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

Through December 2025.

Guided Tour with Sandra Sánchez: Saturday, October 18 | 1 pm

HANGOUTS

Session 2: Wednesday, October 22 | 7 pm. La pintura como medio para pensar, género, cuerpo y memoria [Painting as a Medium for Thinking: Gender, Body, and Memory]. Moderator: Octavio Avendaño. Artists: Nicole Chaput, Manuela Solano, and Edgar Cobián

Session 3: Thursday, November 13 | 7 pm. [Posibilidades expandidas de la pintura] Expanded Possibilities of Painting. Moderators: Bruno Enciso and Alberto Ríos de la Rosa. Artists: Eric Valencia, César Rangel, Eva Van Der Horst, and Manuel Forte

Session 4: Thursday, November 20 | 7 pm. Cecilia Granara: I Paint So I Don’t Kill Myself. Moderator: Alejandro Sordo. Artist: Cecilia Granara

Session 5: Thursday, December 11 | 7 pm. La pintura mexicana en la actualidad: identidad y circulación. Mexican Painting Today: Identity and Circulation. Moderators: Mercedes Sáenz and Diana Vega (Lote A). Artists: Rafael Uriegas and Eugenia Martínez

Published on October 17 2025