Interview

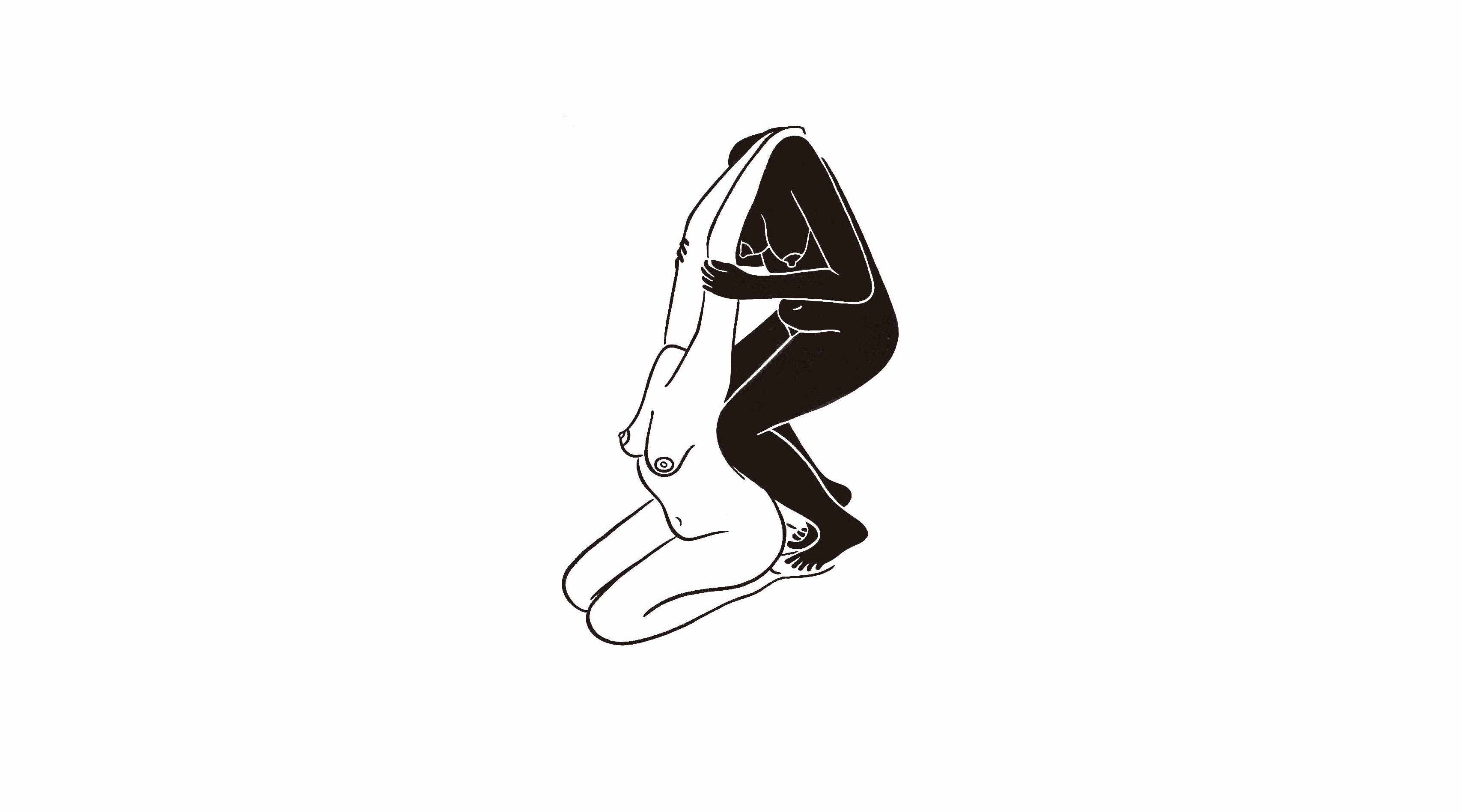

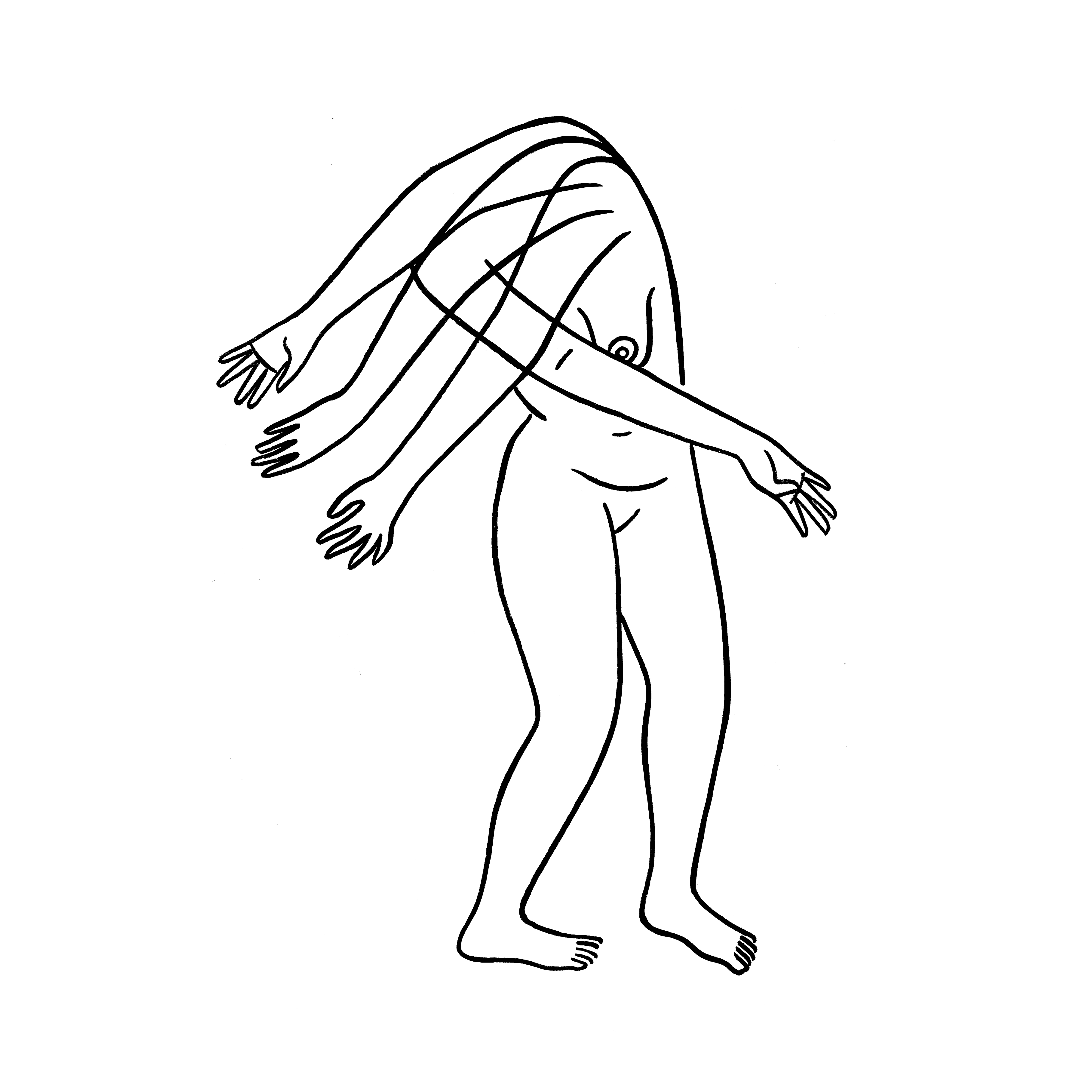

The Bodies of María Conejo

by Sandra Sánchez

Reading time

12 min

María Conejo is an artist who investigates the body and its affective relations, in different media. As part of a series of texts about Mexico City illustrators, I spoke with her about her drawings, which break with any aesthetic paradigm of contemplation in order to point to an active and powerful presence.

The strokes begin at the line until they form black contours of human figures on a white background, highlighting postures, moods, and movements. María’s bodies are naked and often have exposed breasts and vulvas; however, the accent is on their different ways and possibilities of acting on themselves. On each surface, the space is a consequence of the bodies and not the other way around, and although they’re the center of attention, they lack any solipsistic narcissism, since they always point to something else, often something difficult to name.

Sandra Sánchez: In your artist statement you say you’re interested in showing the female body as a sign and as a communicating gesture. I’d like to invite you to concretize this idea, and to wander with it: What kind of sign? Has it changed over time? What’s stayed, and what have you abandoned?

María Conejo: I arrived at the subject of the body while drawing about my emotions, about my state of mind, when I hadn’t even yet considered dedicating myself to doing this full time or to being an artist. One day the body lost its head. When this happened and it became just a body, it began to communicate things to me in different positions, to represent states of mind from the point of abstraction.

I think the body’s a sign because it’s in a position that says something without needing to have a background, a setting, or something written. And it doesn’t need textures or colors either. I like the idea that the image is a concrete, powerful center, and that it doesn’t have noise coming from any other thing, that it’s only that body and nothing else.

When I started drawing, it was from a very naive position; I liked it and it was something I had done since I was little. Then several important things happened to me. I worked at LABOR, a contemporary art gallery. That’s when I realized that art has a certain structure; it’s a business and artists think in a specific way. For many years I worked for Pedro Reyes, and this made me see art production in a different way: taking it seriously as a thing, really drawing every day, making it a part of life. Pedro has a huge library, so I had access to all his books and to him. When he saw that I had certain concerns, he would share references with me.

The sign that started out as a naive thing (one day I published a character who lost her head for love, this character is part of the themes I had already dealt with: my love complications, my personal conflicts), suddenly connected with a deeper part of me, my human experience, and how I’ve felt with my body.

At first it was a body that wasn’t even well-drawn. The bodies were very thin; I think that was a part of my life, too. The ideal body had to be a certain way: perfect, slim, agile. I thought it was poetic and beautiful for being ideal.

As I got to know more references and I became more focused on feminism, drawing the body became a process of accepting my own body. That body that belonged to one form converted into another type of body that I now question. What possibilities for the body are there? It can have more than two arms if I want. In this drawing, I’ve been allowing myself to explore different representations.

Now in the pandemic I’m thinking of the body in relation to its internet avatar. In confinement I was reading science fiction and I came across cyberfeminism; it proposes that the body’s liberation takes place on the internet where gender no longer exists or imprisons you.

SS: In your drawings, the body isn’t positioned for someone to contemplate it, and neither does it offer an essentialism or a definition; rather, it’s in motion, activating something in relation to a space that’s not filled with content, but that certainly exists. I see it and I think of it as a scene, as a mask, and as a disguise. Do you feel close to the mask and to the disguise?

MC: Right now I’m taking a workshop with a writer, Tamara Tenenbaum. On Friday we were talking about gender and how it’s a disguise in the sense that everything we believe, that we know, that’s a part of our life, allows us to be: we put ourselves in a role that allows us to relate to the rest of the world, but in the end, yes, I think it’s a kind of disguise.

My drawings start out from my thoughts. All the time I’m keeping a log, writing how I feel. Something that really interests me is questioning all the time and truly knowing myself. Understanding where my emotions come from, why I feel the way I do, and how all the things I learn and come to know over time are incorporated into my life. That’s also been very important.

If I have any existential, personal, or emotional conflict, I write it down. After writing I come upon an abstract shape in my head. The drawing is the body that’s communicating that.

I’ve always been interested in starting out from my personal experience. Something that happened to me when I first began to draw constantly and to show my drawings, was that I realized that those things that I think and feel are not just what I think. I already knew it, but it became clearer to me when other people told me: “I feel that way.” Although my drawings don’t seem to say anything because the expressions are abstract, there are people who identify with them and let me know it.

I started to realize that when I talk about my body I’m not just talking about my body; I’m talking about the body of many other women and of people who experience life in a certain way.

SS: There’s an explicit and constant dissociation between the face and the body in your work. In an interview with María Olivera, you explained that the figure started out from the feeling of “having lost your head.”* However, now that head appears in some drawings doing things; it’s gained a certain autonomy. Could you tell us more about how today you understand the relationship between head and body?

MC: When the body lost its head, it was carried away by emotions; it wasn’t thinking and was only reacting to what it felt and experienced. Then I thought that wasn’t so good. There exists a dichotomy that says that the head is what thinks—and it’s associated with men, while women are always more related to emotions. That led me to think that this headless body is a body that’s inside the mind: it’s a thought.

Sometimes there are things that are very abstract for me, but the moment they take shape on paper they make sense of what I think and feel. I don’t necessarily articulate it to myself beforehand. My language and my form of thinking are visual. I think in shapes and not so much in concepts.

I also feel that emotions aren’t a bodily thing, but rather something that we think. I’ve been reading about the affective turn, research on the importance of emotions in our lives. They’ve never been given very much importance, which leads to the thought that women are very emotional, so they must be segregated and prohibited from having a certain power. Their emotions don’t let them think.

For me emotions are very important, the way we feel about certain things depends on our context, the freedoms we have or not, the privileges we have or not, our life experiences, our experiences of oppression or freedom; all of this defines the way we perceive the world and how we feel inhabiting it. In my work I’m interested not in separating the body from the mind, but rather in seeing how they depend on each other and on other things.

SS: I think your drawings leave many areas of indeterminacy for viewers to fill in with specific stories or content. Could you tell us if the women you draw in duos or multiples are the same woman, divided, or instead several?

MC: It’s the same one struggling with herself. One that’s many in the head. One that wants to do something, but at the same time doesn’t do it because it scares her, or for some other reason. They reflect an internal struggle: always to be debating in the head. It happens to me all the time: that I’m the very voice that oppresses me.

The fact of not putting a face to the body allows the body to remain in its own concept. My bodies are my age, they grow with me, they share my temporality; however, they can be of whoever I want. I have male friends who say they identify with them, even though the body I draw has breasts or a pussy.

Drawings are like a coloring book; you can put the colors you want or you can put them in the scenario you want, and I like that.

SS: The penultimate question is about your imagination and your references, both delimited by the body and beyond it, both in art and outside of it.

MC: Lately I’ve been going over more philosophers than artists. Right now I’m nailed to Sara Ahmed. She’s allowed me to put the affective turn into words, something I’ve been thinking about for a long time.

I just took a science fiction workshop with Gabriela Damián Miravete that led me to think about the possibilities of expanding the body. I read Ursula K. Le Guin, and right now my mind’s blown because it makes me think about what other possibilities there are for corporality. The workshop seemed pretty cool to me: man says that the first tool humans created was a weapon for self-defense, but what if we thought that the first tool humans created was a bag for gathering fruit and for sharing it with others?

There are a lot of photographers that I really like, such as Flor Garduño. Mary Frank has some drawings of bodies that I also find very interesting.

SS: This interview is part of a series on illustration that we’re doing at Onda MX. I’d like to know how you relate to this discipline and if you consider your practice close to it or not.

MC: This is a question that’s caused me the biggest conflict of my life. When I left design school I thought I was going to be a designer, but I made a decision: I wasn’t going to do advertising, to convince anyone to buy things, or to lie. All I wanted was to use the tools I had in order to invite someone to see an exhibition, to read a book, and so on.

At LABOR, with Pedro, and in production work for other artists, I came to understand contemporary art. When I worked with Pedro, I saw all the things that he did. In a way, I was a part of his projects and processes. When I started making my drawings, I wanted to be like Pedro—to exhibit, to have a gallery, to go to a museum, but the drawings I was doing were more like illustrations. Everyone said, “They’re illustrations.” They would look for me to publish them as illustrations in magazines.

I don’t think that way now, but at the time I didn’t want to be an illustrator; I felt that calling myself an illustrator took me down a level. I got involved in a workshop at the Centro Cultural Border, a consultancy for artists, and my conflict was just that: I wanted to stop being an illustrator and to be a real artist.

I think I do something other than illustration. In my mind, an illustrator is always doing things commissioned by someone, from something that’s not internal. There’s something that’s explained with drawings, that may or may not have text, but that involves something external.

I call my work drawing because it starts out from my personal concerns, my thoughts, my feelings.

In all this making and drawing, the gallery Machete invited me to exhibit at Salón Acme. There the drawings were placed in a contemporary art context. I stopped understanding. Some called it illustration, others contemporary art. Ever since I exposed at Acme, I said: “It doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter what it is or how they want to categorize it. Rather, if there’s a possibility that I can express something with my drawings or my ideas, be it an illustration or with a publisher, that’s fine.”

I’ve also been very foolish in always having the creative freedom to do whatever I want. They’re my drawings, they’re naked, they have exposed breasts, sometimes you can see their vulvas, they don’t have heads…It’s something I’ll never modify to suit the client. That's the way I've carried on.

.jpg?alt=media&token=62b4a8cf-4e56-4c73-982e-de92c1bef06c)

*Translator’s note: “perder la cabeza” (literally, “to lose one’s head”) is the equivalent in English of “to lose one’s mind.”

Translated by Byron Davies

Published on September 10 2020