Review

The Spiritual Life of Things: On "Aura significa soplo" by Ana Navas

by Mariel Vela

At Pequod Co.

Reading time

8 min

There are times when the footnote is its own universe: an insistence, an invocation, a quotation. Footnote (2021) by Ana Navas is the first piece I see and that I yearn to walk through, this mire of objects at the bottom of the gallery Pequod Co.'s pop up at Laguna. It immediately sends me back to the “hood that glistens with large pipes”*1 belonging to a racing car, like those appearing in “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism,” perhaps owing to the chrome appearance of what is more like a Revlon iron, a Nespresso coffee machine, an electric juicer, a Dyson hair dryer, a face massager, and a small epilator, for such delicate areas as the face or the bikini line. Everyday objects, accumulated by a true collecting spirit, which, as Walter Benjamin points out, “does not emphasize their functional, utilitarian value—that is, their usefulness—but studies and loves them as the scene, the stage, of their fate.”*2

Aura significa soplo [Aura Means Breath], a solo exhibition by Ana Navas, curated Fabiola Iza, offers a review of certain objects and their forms as momentary configurations of a modern spirit, in which—beyond any time frame—a particular way of feeling towards things is revealed. Bringing art to life or creating the everyday are ideas that emerged at the beginning of the twentieth century with the “comrade” objects of Russian Constructivism*3 and the revolutionary forces that surrealist poetry mobilized in the first constructions out of iron, or in a snail, or in an old photo. (“So, too, for Breton. He is closer to the things that Nadja is close to than to her.”)*4 Through an assemblage of images, the four recent bodies of Navas’s work present modernity as fragments: samples in which it becomes possible to tighten new relationships with the past.

The series Transparencias (2020-2021) is made up of translucent fabrics mounted on metal frames, and on which there appear printed and spliced photographs of old museums—all since disappeared—like the Musée de l’Homme and the Musée Ethnographique du Trocadéro in Paris. If the exhibition is seen as a theater production, these would be the spectral curtains delimiting movement in space. A choreography in which the old world of diaphanous and delicate display cabinets is limited to the collection of electrical appliances traversed in Footnote: two parenthetical signs bringing together ways of organizing beings, classifications, and taxonomies of the animate. “Museums: cemeteries! Identical, really, in the horrible promiscuity of so many bodies scarcely known to one another.”*5Ana Navas seeks to generate associative comings and goings through her assemblages of reproductions and reinterpretations. Unlike the futurists, she does not destroy the image of the display case, but rather presents it in relation to the work; it is this that facilitates access to a series of complex sensations towards the pieces. I continue thinking of Footnote as a car body that I want to drive after having tied one of those fabrics (the one with the golden parrots) in my hair.

_ananavas.jpeg?alt=media&token=bc533275-7cef-44f7-8aa0-c0a83a637e1b)

A pattern is an unfolded silhouette, a volume turned smooth surface. The series Patrones [Patterns] (2020-2021) functions as a hinge in which there is articulated a story of correspondence between fashion, design, and the work of art. Un insecto (con antenas y alas) (2021) has a print combining images by Mondrian and Kandinsky, as well as of secret functionality. What use can be made of that geometry? If Walter Benjamin argued that the proliferation of images caused the fading of the aura—the fading of the work of art’s state of uniqueness—Ana Navas denounces the impossibility of thinking about an origin. I instead observe an interest in the life cycle of forms, their reiterations, and our insistence before them. There is no purity in this idea, nor in a magnet of Christina’s World (1948) on the refrigerator door, nor in having The Garden of Earthly Delights (1485) on my planner. But there is an amateur exercise: an incompetent but sincere love towards these images.

The abstract molds of the Patrones series (2020-2021) take on a different meaning when one looks at the dressed objects of another series, Disfraces [Disguises] (2020-2021). The act of speculating on what lies under the fabric then takes on even more intrigue with such titles as Busto de mujer triste and Leda. With Musa (2021), Navas has reversed the industrialized printing process by replicating the design of an Ikea sheet with the Shibori dyeing technique. I think of the patterns by Varvara Stepanova, constructivist-productivist, and of her pictorial architectures in which painting is turned into graphic arts, into printing: “Day and night she sat making her drawings for fabrics, attempting in one creative act to unite the demands of economics, the laws of exterior design and the mysterious taste of the peasant woman from Tula.”*6. Printing an economic flow, a commodity, but also the mysterious taste of those who created an image for their industrialized production. Using Shibori to dye the disguise of a household appliance, giving it a mystery of its own; turning it into a sculptural object.

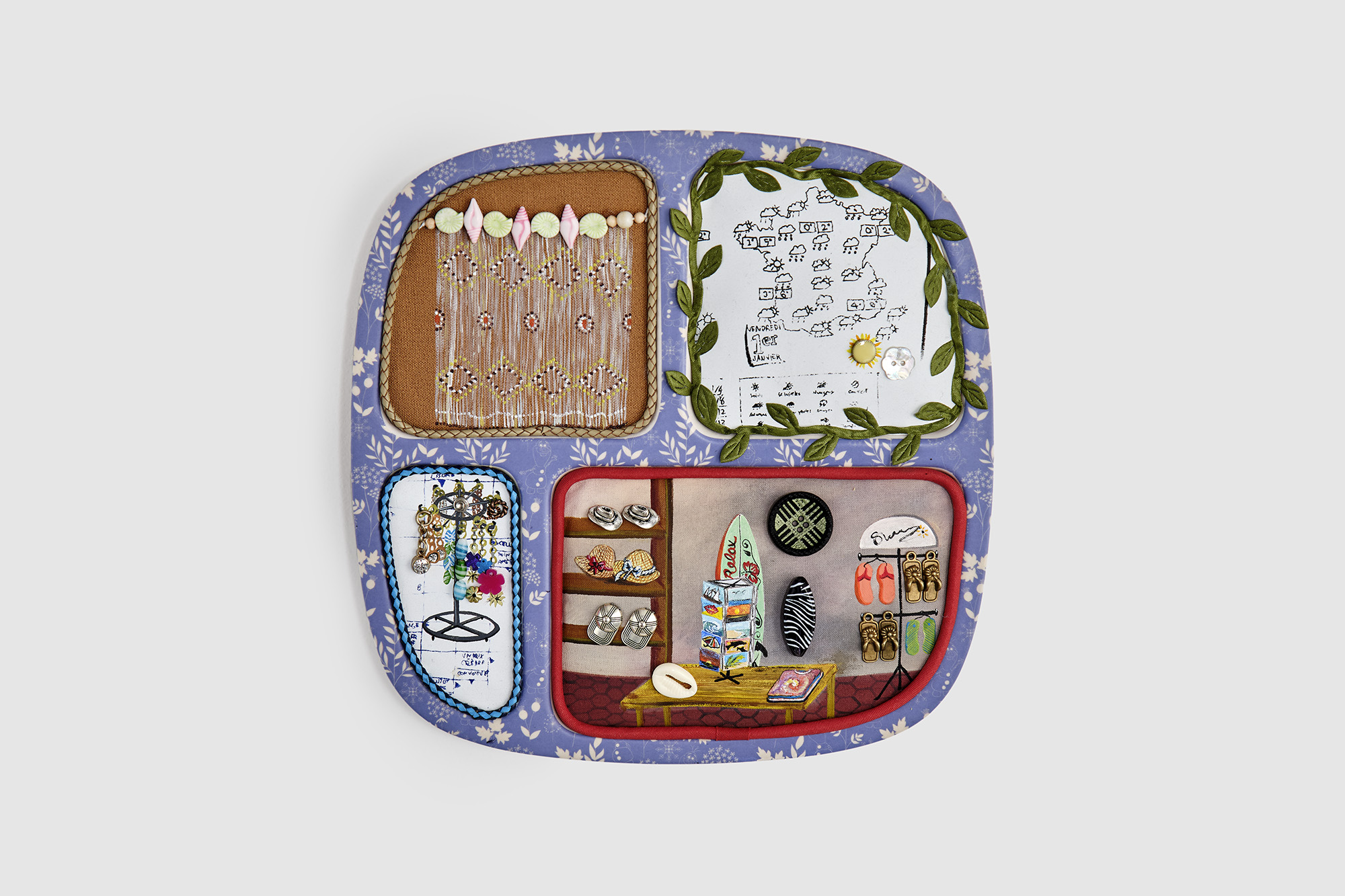

After visiting these pieces, nearly all of medium scale, I arrive at the end of the exhibition, where there are four plates in which miniature stagings have been created for a cafeteria, a natural history museum, and a souvenir shop, as well as the tiny showcase of Todo D’Vidrio (2021). They remind me of the cell layouts I saw in school, and of the orderings of their inner parts. The mitochondria would seem like candy and the nucleus would cause in me an excruciating tenderness, a reaction that I might define as seeing-eating and that I experience once again with the series Platos [Plates] (2020-2021). In the text written by Fabiola Iza for the exhibition, she mentions, in relation to these pieces, the spatial logic of a tourist shop. Both in the scale and in the segmented organization of the scenes built into each division, there is indeed the spatial logic of a tourist shop in the sense that they present a sentimental journey, the possibility of materializing those emotions we have towards a place. The natural history museum displays its accumulation of arrows, rugs, and tiny vessels. The fact that it is arranged so close to the “latte art” of the Caféothèque—or to the tiki curtain of the Souvenir Shop—provides us with the opportunity for establishing ominously pleasant assemblages, and this also reminds us that any kind of collecting presents us with the theater of fate, the staging of a relationship towards things.

In Aura significa soplo modernity is that which pulls back while pushing forward, a project that never arrives, an unresolved desire. It is also, however, the grandmother who dresses her blender with quilted padding, a poster of Klimt’s Kiss adorning the office, as well as the shiny, thick plastic covering elegant armchairs, or an Empire State Building keychain. Speaking personally, it was the sophistication of the poster of a Degas ballerina in my friend’s room in high school, in perfect harmony with the white satin canopy that covered her bed. Many will say: the hell of modernity. I prefer to think of these as the unfoldings of the yet-to-come.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: F.T. Marinetti, "Le Futurisme,” Le Figaro, February 20, 1909. Translated into English as “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism” in Futurism: An Anthology, edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009), pp. 49-53.

*2: Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library: A Talk about Collecting,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 2, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999), pp. 486-493, 487.

*3: “Everyday Life and the Culture of the Thing” was written by Boris Arvatov in 1925. Arvatov proposed ways in which socialism could “transform passive capitalist economies into active socialist things.” Quoted in Christina Kiaer, “‘Into Production!’: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism,” Traversal Texts 9 (2010): https://transversal.at/transversal/0910/kiaer/en

*4: Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 2, Part 1, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999), pp. 207-221.

*5: F.T. Marinetti, “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism,” p. 52.

*6: “Pamiati L.S. Popovoi,” Lef, 2 (1924), p. 4, quoted in Kiaer, “‘Into Production!’: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism,” Traversal Texts 9 (2010): https://transversal.at/transversal/0910/kiaer/en

Published on October 23 2021