Review

It started as a dream and ended up in my notebook… Natalia Berzunza at Momoroom

by Verana Codina

Reading time

4 min

Too much text

I remember the first time at school that I was allowed to write in print instead of cursive. In Buenos Aires, where I lived until I was eight years old, the method used to learn writing begins compulsorily with cursive, until finally in third grade—once you have mastered your stroke—you can choose whether to switch to print and (what was even more exciting) from fountain pen to a simple BIC.

The obvious response from a curious girl of that age was, automatically, to choose the novelty. This was in addition to the fact that, in my eyes, I considered cursive boring, too elegant, over-elaborate, and less cool than the “normal” handwriting. Nevertheless, none of us knew that trying out this new way of writing would imply, from getting out of the habit, an extra effort when trying to straighten the curve that we had learned to twist for years.

Excited that for the first time we were offered the possibility of choice, without questioning it we launched ourselves into unlearning and reversing the educational process of years of calligraphy sheets and other exercises meant for tracing correctly, always forced to take care that the edges of the letters thinly brushed the lines of the rows.

I think a lot about how embarking on the path of writing away from cursive continues the legacy of the scratches and scribbles with which we began to communicate. At what point do we stop tracing in order to draw and then start tracing in order to write? From meaningless lines we pass to meaningful lines, which are lines in any case.

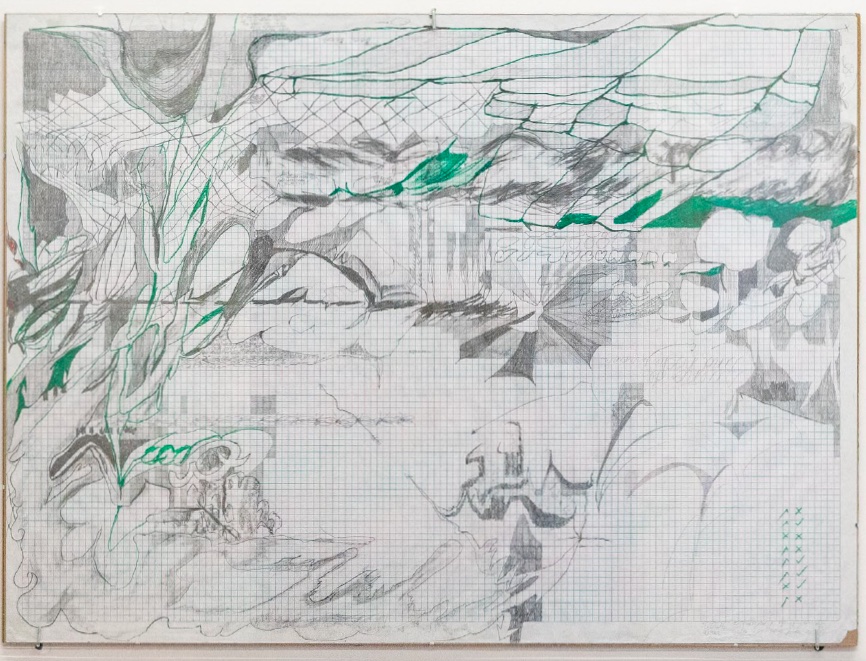

I place the work of Natalia Berzunza—or Miss Kiti, as her drawing and ceramics students quite aptly refer to her—right in the middle of this transition. She follows her own school, one where writing and drawing are synchronized until pieces are achieved that are as calligraphic as they are plastic.

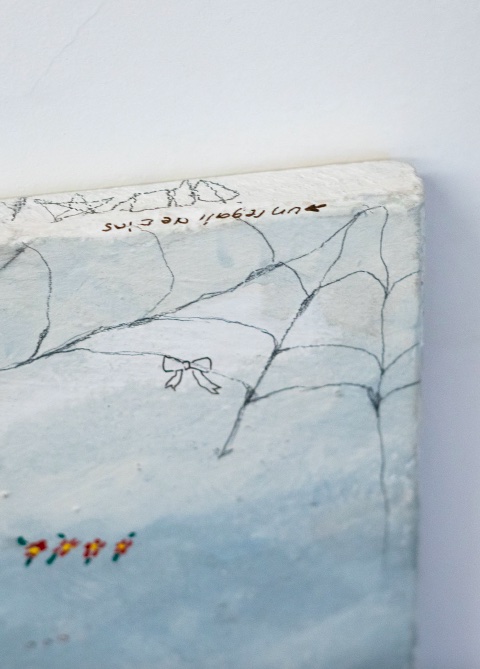

For her first solo exhibition at momo room, Kiti brings together a set of works that includes six drawings, two paintings, (several) ceramic keys, and a curatorial text written by herself and her close friend Gibrán Turón. The care taken in every detail of the curating was present on opening day both in the musical choice (Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me by The Cure) and in the edible art (gelatins that she made with her mother in order to share with guests), but above all in the choice of title, which suggests precisely the two themes typically running throughout her work—romance and writing. It started as a dream and ended up in my notebook, like the lyrics of a song: the only thing worth talking about is love: this could only come from an eternal romantic like Natalia.

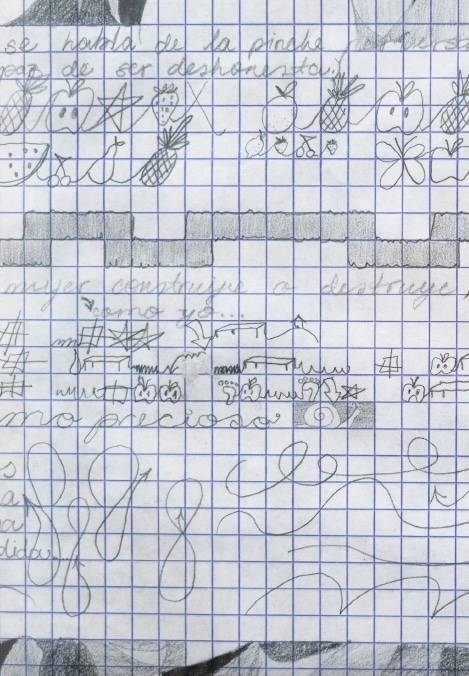

And just as her dreams end up in her notebook, so they do on her canvases, ceramics, and papers where hidden messages suddenly appear, ready to be deciphered. Kiti always carries gridded notebooks with spiral spines, the kind where the weight of the paper is so low that any ink goes straight through the page. What for others are mere incidents, for her are eventualities that construct, in this case, a visuality of smudges and blurs caused by graphite and ink.

For me, choosing print over cursive is comparable to choosing smudge over touch-up. The artist puts error before correction and conflict before fluidity, the disparate before the homogenous; nevertheless, the results are cohesive. Her work is a constant process of unlearning, whereby “finished” is not synonymous with “complete.” Especially in her ceramics, the pieces are not defined by the regularity of their finishes, but rather by the process of experimentation, both materially and emotionally.

Although I detect a wink shared by Natalia’s work and that of Cy Twombly, I see that while Twombly’s scratches and fragments come from the great epic narratives, from founding myths and the history of Greco-Roman antiquity, in Kiti’s work they arise from her own sensations. Her loose lines, occasionally victims of her own freedom, revisit her own history and, in an act of self-love, she surrenders to them, hoping that her own words will instruct her once again.

These mental-emotional maps—constructed with alphabet soup and encrypted messages, scribbles and drawings—have the peculiarity of working not only for the artist, but for whoever is entrusted to them since their language is romance, and romance (if it’s sincere) is universal.

Translated to Enfglish by Byron Davies

Published on March 30 2023