Essay

Correspondence 'On diplopia and other forms of seeing' by Marek Wolfryd

by El Cuarto de los ojos Sucios

Reading time

9 min

…even if people will examine the powder from Rubens and all his art—a mass of ideas will arise in people,

and will be often more alive than actual representation (and take up less room).

— Kazimir Malévich

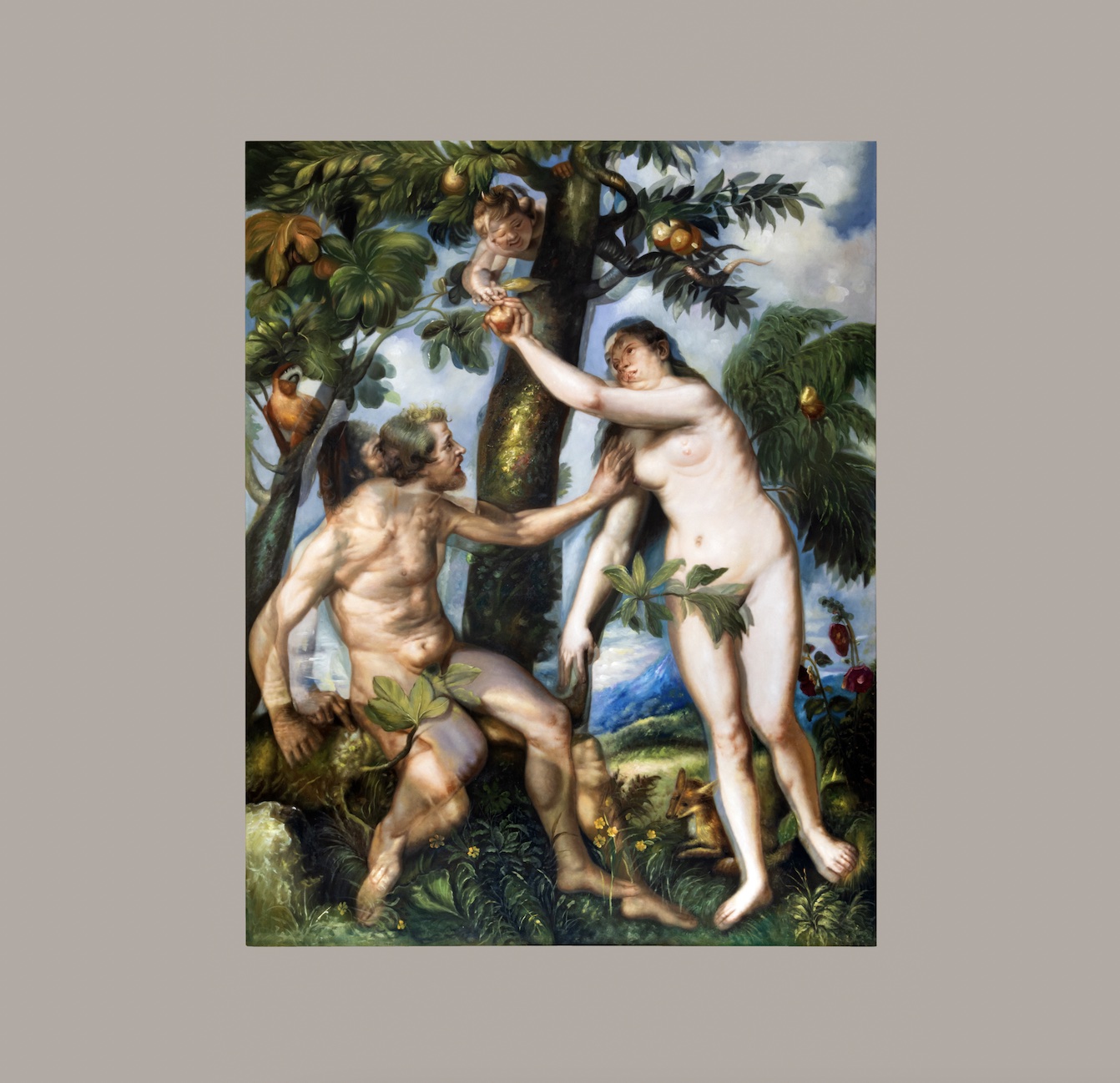

This correspondence stems from the surprise and enthusiasm we felt when we saw Marek Wolfryd's paintings as part of the exhibition Il Divino y los mundanos, at Anuar Maauad's studio. Both presented separate works and a collaborative piece; they started from an acquisition made by Maauad, Guido Reni's Muse Erato, dedicated to lyric, love, eroticism, and mimicry. This last element is the common thread between the two artists. On the one hand, Maauad is interested in understanding production logics of other times (Reni lived from 1575 to 1642 and had a studio where more than 100 people worked) that are difficult for the authentication–for the law–of a present where the artist is one because the name–white wall, black hole, as Deleuze and Guattari would say–is the perfect place to accumulate meaning and, then, surplus value. On the other hand, Marek has been working on the problem of the original work for a long time, of how that original piece is supported by a fictional story that often contradicts the historiography of objects; for example, he has a study in which he demystifies the sphere as an element used in ancient Western cultures as a cosmic form and relocates it to the modern era, the time that invented it as a form of the past. Anachronisms, Didi-Huberman would say. From the exhibition we will only focus–because of the haste to write the text and also because of the feasible extension of it–on the paintings by Marek, who had them made by three companies¹ in China with the instruction to splice one painting over another, evidencing what one artist took and modified from another. There are also paintings made by the same artist that work the same subject in two different paintings: Leonardo Da Vinci's Virgin of the Rocks. One in the Louvre, the other in the National Gallery. Guido himself resorted to technical reproducibility in painting: he made copies of his originals–although this is not the case of The Muse Erato.

Eric, Hello,

What if the vocative is the "hello" and not the name? Hahaha. Sorry, I'm excited and when I get excited everything starts to get messy; the threshold of mania. While we were having lunch near Maauad's studio, in the beautiful fold that is Colonia San Rafael, I was telling you that the superposition (painting over painting) in Marek's series takes a step away from Byzantine and Romanesque art–where it was rehearsed long before the Dada collages. In the Middle Ages, superimposition served to indicate hierarchy, hand in hand with the line–the more in front the figure, the more important; the thicker the black line, the more definition. In Marek's paintings the superimposition makes ghosts appear. And we love ghosts; we can think of Aby Warburg–and the survival of forms,–of Didi-Huberman–and the gesture as that which generates the political,–of Freud and Lacan–and repetition; the repressed that always returns: the "return of the real." However, you and I prefer to speak of Deleuze–always Deleuze–and of Guattari–always Guattari; of how an artist is the medium of collective agency (it is not that the muse dictates what to do, as in Plato's Ion, but that the artist tempers his body to receive and reject, to desire on the basis of cuts and flux). Collective agency is that which speaks through us: all the signs, impulses, forms and modes that we modulate, choreograph and pass from one side to the other. Often unconsciously. The painter as Hermes and as Bacchus in the care of Apollo. And Apollo here is perhaps the color and the materiality of the painting that halts and gives a possibility to its expressiveness. The painter, like any other person, transfigures; only that his tools–Hefesto–are the canvas, the color, the turpentine, the oil and the infinite-finite that he can conjure with them. There is no painter, there is assemblage. I would like to tell you how my friend Isaac wrote a beautiful text that he read to us in class where he says that all psychoanalysts are trans because we transform, transit, metamorphose and perform in order to listen. The famous transference love. It is not about what we think, but about transfiguring a listening that gives back to the other, the analysand, something of his own collective agency and of the place he has given to it in his life. And if we are other, if we are trans, then there is no psychoanalyst, no painter, no subject. But I'll leave that for another coffee.

Hugs,

San.

Hi San.

Yes. In addition to the superimposition, we see that in Marek's paintings from the series On Diplopia and Other Ways of Seeing there is work done with transparency, and (I think) that prevents the images from being arranged in hierarchies. Riegl (Delueze said) said that in Egyptian bas-relief, the outline separated the figure from the background in order to separate the eternal essence of the character from the passing of the world; and only the slaves and the dead had broken or open outlines.

But what we see here, to be more exact, are figures that share contours. This produces a greater consistency in the forms that are repeated, while the variations appear more transparent; yes, more "ghostly." It is as if these paintings formally respond to a statistical problem, but I still don't quite see in pursuit of what.

Hello, Eric.

Jens Andermann in the introduction to the book Natura. Environmental Aesthetics After Landscape quotes anthropologist Michael Taussig² and says that the concept, by abstracting reality, produces a sublime of itself–this happens by condensing the magnitude of the multiple to a unity; Taussig's bet is to desublimate the concept. I believe that this operation is a political way of combating the fixed identities that lead to sadness and fascism. Today I was discussing with my students, how to desublimate the concept? We think that by making it not something fixed, but something porous; a place that preserves the limit, while transforming it at the same time. The concept engaging on a critical paranoia with itself; attending to its own collective agency, its inherent metaphysics, and its aesthetic production, that is to say, its fiction: it is as if it could account for reality. All this reminded me that you told me that Bergson had said that we should doubt the self, the productive narcissism of the self (you said it in other words); I answered you with Simone Weil and the impersonal: the Marxist mystic imagined in Gravity and Grace that there could be a productive moment that was not aesthetic (that did not start from what causes pleasure or displeasure to the subject). I feel this all has to do with Marek's paintings and what you point out in your response. I was very moved by the superimpositions and now I understand that pictorially it is the glazing that allows the critical moment of dismantling: it slits the pictorial conceptualization to let something else through; it desublimates the painting as a unit–following Taussig. I found it very relevant that you did not let your guard down and that you indicated how every force contains its opposite, how the coincidence of the contour can once more generate the illusion of symbol and unity.

That concludes this correspondence, not this conversation.

Lovely afternoon,

San.

Hi, San.

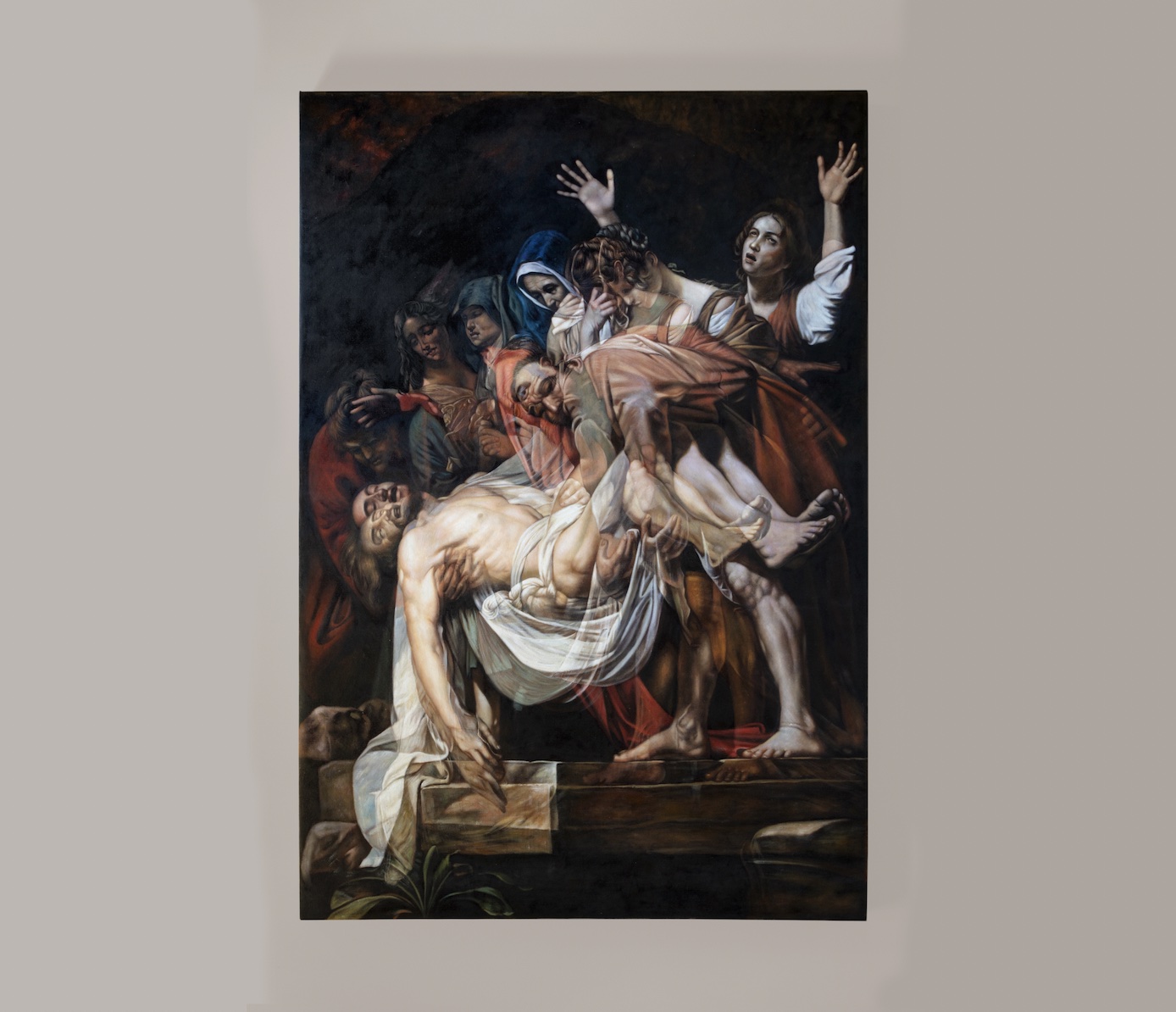

I remember on the tour, while we were watching The entombment, you suggested that even before the paintings, we could consider that the truly original version of the image was the projection of the models in Caravaggio's studio: "The original was the projection in the camera obscura; it was in cinema!" you said.

In this order of ideas, I believe that cinema, insofar as it is projected by light, has the capacity to make two images (or two sequences of images) coexist at the same time in the same space. And that is already a montage.

I write all this being a little redundant about the ideas of your last message: that the concept and the percept produce a sublime of themselves. How do we desublimate them? What do we do with their ruins, once they have become an event? I agree that there is much in Marek's work that can be understood in this sense: the way he uses the resource of montage, in painting, as a kind of simulacrum of "overexposure" to treat masterpieces as fragments of a much larger chain that, above all, does not culminate in them.

Thanks for the conversation.

Eric.

— El Cuatro de los ojos Sucios³

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

1: On this occasion Marek Wolfryd worked with Xiamen RuoYa Arts And Crafts Co., Ltd; SOA Arts Co., Ltd and Nanan Yihui Painting & Arts Fty Co., Ltd.

2: “Michael Taussig writes quoting Hegel, postnatural arts and theory also have to learn from (and with) their indigenous allies the art of "mastery of non mastery," which "is built on resistance to abstraction and tilted toward sensuous knowledge which perforce includes desublimation of the concept into body and image." What these translocal forms of alliance might give rise to is not "conservation" but a shared becoming, a model of queer community that is not exclusive to the human and in which, nonetheless, the human might still aspire to some form of afterlife.” Michael Taussig, The Corn Wolf (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), p. 145, quoted in Jens Andermann, Lisa Blackmore, Dayron Carrillo Morell (Ed.), Natura. Environmental Aesthetics After Landscape (Zurich: DiAphAnEs, 2018), p. 15.

3: El cuarto de los ojos sucios [The Dirty Eye Room] (2015-) is a mediation and curatorial project specialized in contemporary painting organized by artists and art critics Sandra Sánchez and Eric Valencia.

Published on May 18 2024