Review

Blessed Viscera: On Venus Atómica by Nicole Chaput

by Mariel Vela

At Karen Huber

Reading time

4 min

[...] in the silence of the night

I make my meat green, fresh

a magic carpet and I take you

over me like a primary nourishment.

The Queen flaps her wings over the colony

and is eaten by God.

Verónica Fisher

The Queen has opened up. She holds her pearly container with both feet, her pelvis embroidered with some unknown skin; she uses one of her fingers to tell you come. It is Venus Atómica (2021), bearing the same name as Nicole Chaput’s first solo exhibition at Karen Huber gallery. The space belonging to the rest of the venerinas is narrow, a blue periwinkle hall with a silver floor, cleaved with heel marks since its inauguration on November 3, like a skating rink. Strange shapes are reflected on the surface of this “mystical temple, clinical space, glamorous zero gravity.”*1

At the end of the 18th century, Clemente Susini created the first Anatomical Venuses for medical schools. The carved organs were to be discovered under each layer of lacquer and resin, while the venerina herself lay there with her pearls, organza, and silk, her glass eyes ajar as if recently dead. Eternally pregnant and ecstatic, their heads were always thrown back like saints. Chaput’s dolls float on the wall and are anatomically incorrect; they sometimes have ribs in their thighs, multiple legs with tangled tendons, or orifices separating the body into irregular halves. A call to the right to decompose? They are flesh returned from the beyond: cursed and patched.

“When these creatures were born, it was impossible to know who they were or where they came from,” writes Roselin Rodríguez. Some time has passed since their arrival and now they bear the particular age of their desire. Fósil de una señorita (2021) is very young and cries like a Lady of Sorrows; she has a pair of braids that are transfigured into legs, as well as a belly swollen like the sun. She lies at the back of the space, in correspondence with Insoportablemente bella (2021), who looks back at her. She is bluish and her legs are full of veins that resemble corals. Instead of a sternum, she has four freshwater pearls, and where her heart should be, there turns a distaff of bones.

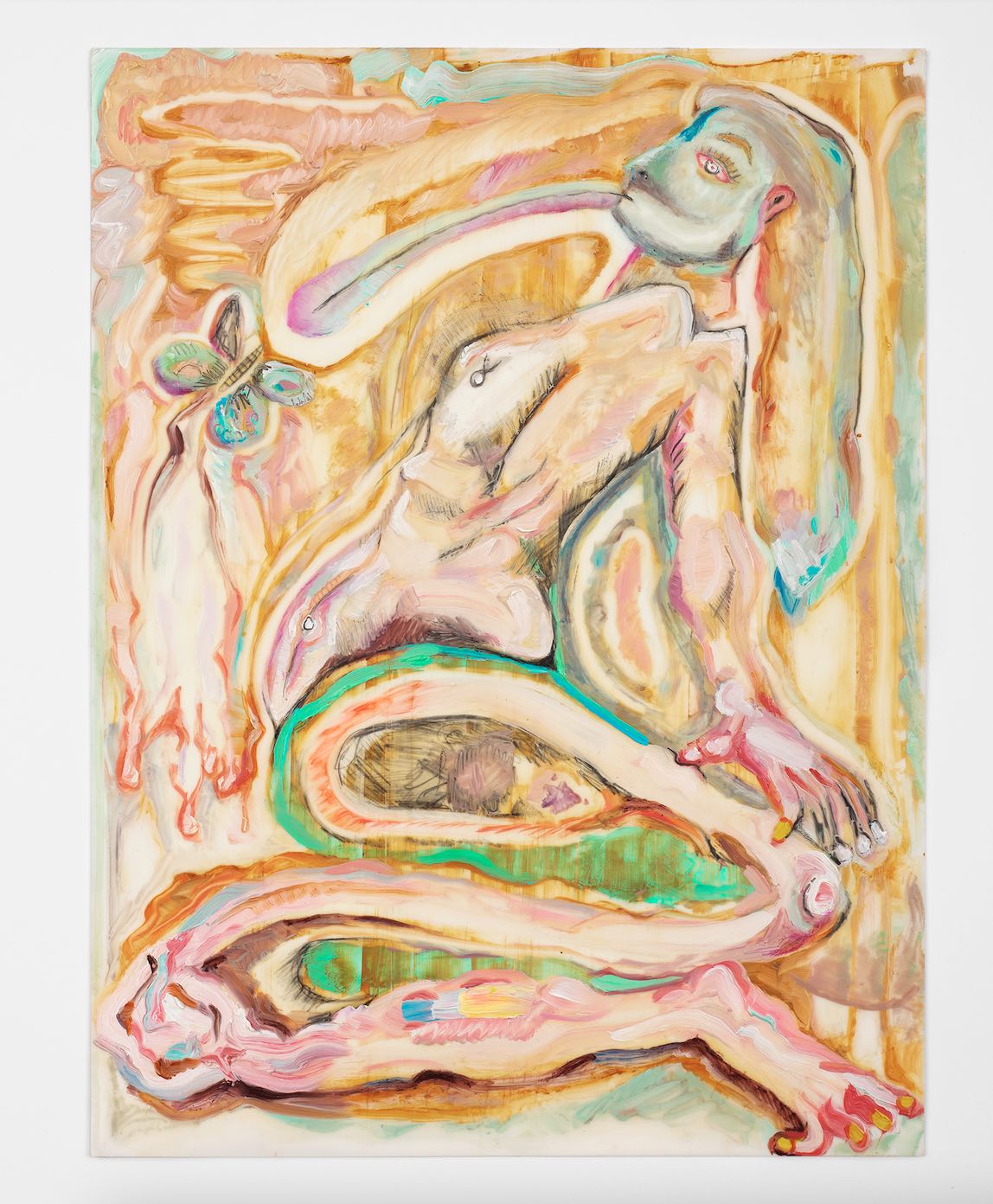

Nicole’s yellows resemble dirty gold and worn-out latex. I think that giallo*2 is the most terrible color—or perhaps it’s the green she uses over and over again. An almost lime green, the color of Freddy Krueger’s blood.

The painting Intestine Mermaid (2021) shows a woman bent on one leg. The sinuosity of her pose expresses the longed-for silhouette of girded, Victorian intestines. First there must be an annulment of anatomical functions in order to begin entering the delirium of forms. The mermaid is in dialogue with the piece titled El Divorcio de mis piernas, in which a woman appears in profile. She has green hair in the concave of her body as well as a long tail—made of wool, silk, and satin—coming out from between her legs, although we don’t know if this has grown out of her or if it is some accessory. In the Middle Ages, there began to be representations of Mary Magdalene with her body covered in dark fur, and showing the period following her decision to live an ascetic and solitary life in the desert.

There’s a mystique in Nicole’s work but also a frankness: What do you do when no one’s looking at you? You use butterfly-shaped beads from your childhood bracelets. You use nail polish for painting your dolls’ fingers. You crawl on all fours. Hairs grow all over your body.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: Karen Huber press release.

*2: In reference to the Italian film genre.

Published on December 13 2021