Essay

A fly is a fly is a fly | Who writes?

by Vivian Abenshushan

At Galería OMR

Reading time

4 min

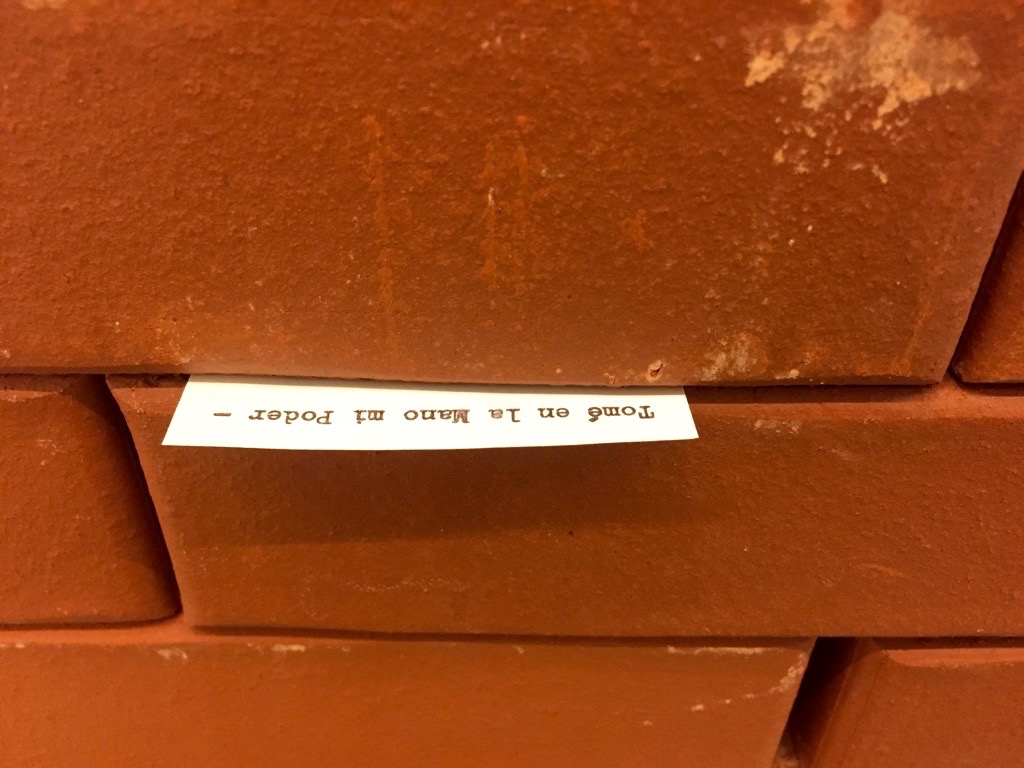

1/ I was being reflected in Shilpa Gupta’s mirror (I Will Die) and thinking about death, when I encountered a fly, like always. Because flies are everywhere, like language. The fly was halted on the wall, or—more precisely—on the brick barrier where the Mexican artist Jorge Méndez Blake had inlaid a card with a phrase by Emily Dickinson in Spanish: “Tomé en la mano mi poder” (“I took my power in my hand”). Dickinson, who wrote locked in her room, with her back turned to the literary system, to syntax, and to male power, also thought many times of flies and death, as in her poem 465: “I heard a Fly buzz—when I died / The Stillness in the Room / Was like the stillness in the air— / Between the Heaves of Storm.” The unexpected fly is not part of the group exhibition Who writes?, curated by Jo Ying Peng for the gallery OMR, and yet I thought I found there, in that insubordination, a key to the show: the lasting presence of writing in contemporary art, its awkward buzz.

2/ “Who writes?” is a troubling question. Not only because it returns us to the question of the materiality of writing, but also because for several decades critics came to pretend that the life of the writer was not relevant to understanding their work. In the 1980s, Edward W. Said, a Palestinian exile in the United States and professor of comparative literature, dedicated a radical essay, The Work, the Text, and the Critic, to rethinking the relationship between writing and context—that is, the material, historical, and social conditions in which writing occurs—thereby introducing a new politics of interpretation into our critical horizon. It is not surprising that Ying Peng, a Taiwanese curator based in Mexico, would take from that essay the very question that brings together works by six artists from different parts of the world, responding to the circumstances that the planetary crisis has imposed on us as a context.

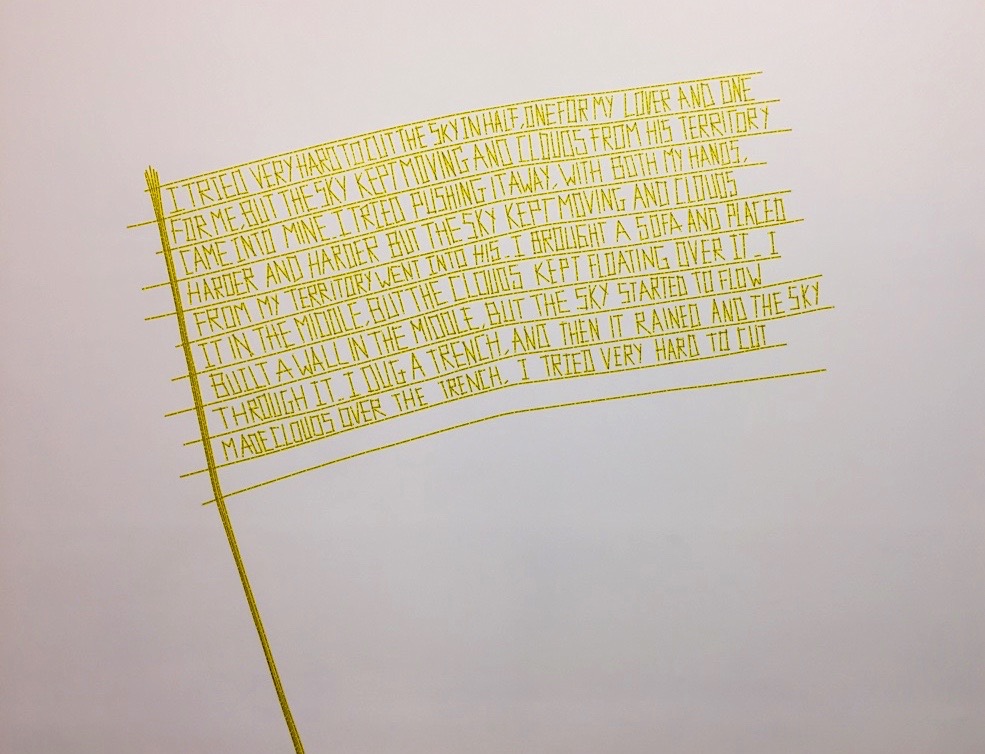

3/ It is here that writing takes a political form, as in Shilpa Gupta’s verbal flag (There is no border here), whose lyricism (“I tried very hard to cut the sky in half”) lays bare the absurd character of borders, or the sculpture Runaways by María Taniguchi: two immense letters (“I” and “O”) made with Java Plum, a wood from India. The letters refer to an electronic interface (input / output), creating a tension between manual labor, nature, and the extractivism that takes from the global south to feed into digital technologies. In addition to its texts, the exhibition explores the possibilities of visual metaphors. In Ariel Schlesinger’s pieces there are no words—and perhaps no explicit insubordination either—and yet a poetic operation takes place: some glasses are transformed into ocular flames (Untitled [glasses] 14:56), while a horizontal candle is held up by two knives. In the middle of the exhibition, a flame—almost as tiny as the fly—dances at the end of a branch (At Arm’s Length IV). Schlesinger interrogates what happens every day, the trivial, the ordinary, what is not seen but nevertheless returns: the infraordinary act that is also a way of resisting news of the spectacle, the artistic or historical fact in its grandiloquent character.

4/ The world, the text, the fly. Perhaps this subtlety is what is most stimulating about the show: the idea that subversion also happens by fissure, by small gestures, by deviations from language, and not only by grand happenings. Hence not all the pieces are explicitly political, although they are all decidedly poetic, as indicated in neon in another piece by Méndez Blake that from a corner hovers over the entire show: Esquina poética (“Poetic Corner”). In this way Who Writes? establishes complex dialogues between territories and languages, between singularity and collectivity, between intimacy and public life, between signs and analogies, revealing the powerful messages that emerge from the crossings between art and writing in order to challenge power.

Published on October 17 2019