Interview

A Conversation with Jerónimo Rüedi

by Gloria Cárdenas

Opposites End Up Touching

Reading time

7 min

Jerónimo Rüedi paints, lives, and works in Mexico City. His studio is located inside Fuego, an artist-run space that he directs along with Ana Segovia and Allan Villavicencio. For the gallery Colector, in San Pedro Garza García, N.L., the artist has prepared the show Al principio el mundo era completamente real (“In the Beginning the World Was Completely Real”), in which he presents his most recent canvases in a space designed for the occasion.

For Rüedi, it’s not enough to talk about things using only words; it’s also important to present them with (or as) a gesture, in order to open up conversations and questions. He seeks to reach nothing in order to reach everything—to reach the meaningless gesture in order to discover the infinity of things that such a nothing can become. Jerónimo truncates the gesture of drawing or doodling the moment he begins to recognize a certain representation, thus generating a dialogue or interrogation regarding what must be said beyond the conventional meaning that a linguistic or social system imparts to things.

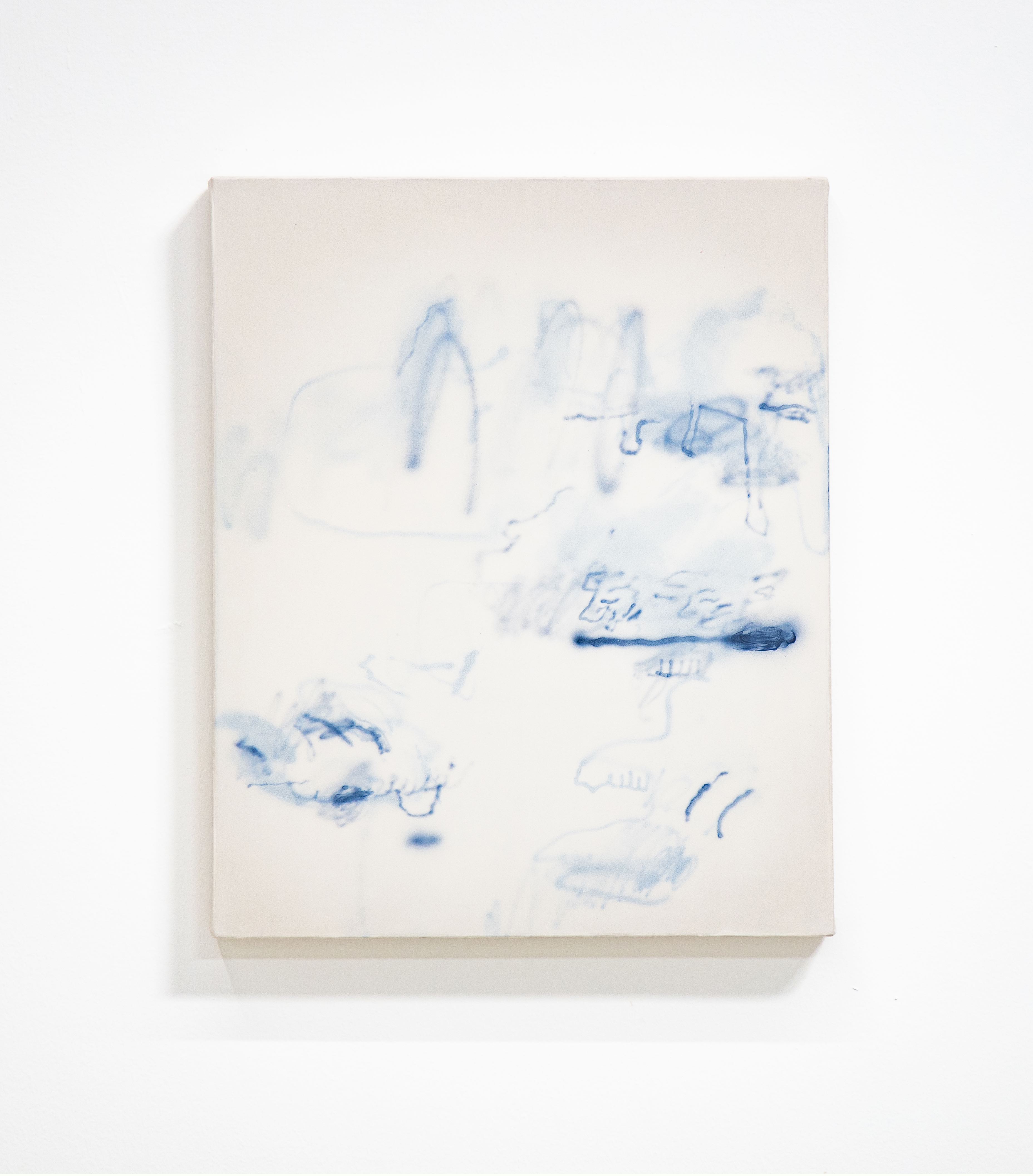

Although there are some pieces that seem to be completely blue, for the most part the pieces have a clear background. This clear, white, or beige tone is a reflection of purity, emptiness, and silence in which completely real things take place.

The pieces are mounted on a wall that seems to be of the same neutral color, but that’s really the effect of sixteen different subtly faded tones from white to beige. With this effect, Jerónimo seeks to contrast the color of each piece with that on which they’re mounted, so that the white pieces are placed on beige and the ivory-colored pieces on white.

One can glimpse gestures that seem to be both there are not there, in almost imperceptible tones as well as in layers covering up strokes that were left behind as more white glazes were added.

The exhibition is the result of processes of introspection, of a constant practice that brings forth space and silence so that things can be heard.

Gloria Cárdenas: How did you get to the point of being able to detect the moment just before your drawings start to represent something? That can’t be easy.

Jerónimo Rüedi: It seems very easy, but it’s not, especially the technical part. I like that dichotomy between a very primitive and immediate gesture and a work that takes months to reach this chromatic surface. I’ve been painting for almost twenty years and this is the show that’s taken more time than any other in my life. I came from something very colorful, and for the last four years I’ve been in a process of deconstruction where I’ve gradually removed certain elements from my painting. First I began to remove colors, to restrict the palette, and then compositionally I began to remove what was left over (the decorative, or the vices passed on by the craft). Beginning to wonder about this last year led me to almost entirely white pieces.

For a moment, I thought that perhaps this was the end, or that maybe I couldn’t continue painting. I had come up with some large canvases that were all white with very minimal black gestures. But then I realized that within that white there were many levels of subtlety where you could begin to use your senses; that’s where those nuances began to come out. I started to be very present in relation to the piece. Now I feel like I could keep doing these kinds of things until I die. What had seemed like a dead end eventually opened up into a giant range of possibilities.

GC: How long did it take you to make these pieces?

JR: For this show, almost a year. What took me a long time to find was the right surface. It took months of going to the studio and spending eight or ten hours a day working on it. Everything was white. There was no gesture, no color. I spent time polishing it, trying out different materials and different types of white, which didn’t work. I ended up throwing away a lot of canvases because the texture wasn’t perfect.

There’s an issue I try not to talk about a lot—so as not to fall into cliché—but it’s important to mention. I meditate every day. Before starting on these pieces, I went to a silent retreat where I spent ten days alone doing meditation. I would never have achieved the work in this series without that practice of silence; with it I surely achieved that patience needed to spend six months trying to make the material work, before making any mark.

GC: But you don’t want people to associate your pieces with meditation.

JR: No, yoga and meditation are linked to certain clichés and western cultural concepts of which I don’t feel a part. And in the end it’s not about that either. My idea is that they’re about absolutely everything and nothing at the same time. If you want in some way to reveal infinity and the whole, you have to go to something very particular and in the end not reveal anything, since the opposites ends up touching.

In order to represent everything, I aim for it not to represent anything. It has to do with the impossibility of communicating through language. It’s a fixation that’s there in both my publishing work and my painting. Language works like a cane we can lean on in order to communicate, but at the same time it’s a cage that we build for ourselves, that doesn’t let you see beyond it. We put too much confidence in it.

It’s not a whim to want something not to be understood; it’s because I believe there’s a reality beyond language that can only be perceived when you go beyond representation, textuality, or anything rational.

GC: What can you tell me about the blue pieces?

JR: The blue pieces are here because I wanted some counterpoints. I wanted the exhibition to be very monochromatic. Ultimately the colors ended up moving toward blue because I think it’s the most neutral color (without falling into black). These pieces use the same kind of technique—they’re many layers of glaze; it’s just that the pigment changes to ultramarine. They serve as the negative of the others, so that when you enter the space there’s a certain strong point of attention. From afar they almost look like holes in the wall.

GC: Tell me about the exhibition’s title. Where does it come from, "Al principio el mundo era completamente real"?

JR: At first the title was a much longer sentence that Kit Schluter and I decided to cut. It’s a fragment that I took from a book by Antonin Artaud (Viaje al país de los Tarahumaras [“Concerning a Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumaras”]) in which he explains what the peyote ceremonies are like, what it means to be there and to return to what we call “the real world.” The sentence said that at the beginning the world was completely real, and it ends by saying that seeing things is seeing infinity. It has a lot to do with meditation, with seeking that thing that’s beyond the “cage” that we build for ourselves. On one occasion I experienced a state of consciousness in which I perceived the world outside of language, without being intellectually assimilated to it. It makes no sense to talk about this since this kind of experience goes beyond what language can explain. This is precisely what the show’s about; the work sort of refers to that essential language-less principle, to the absolute perception of reality.

The exhibition will be open until October 30th, 2020.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Cover picture: Jerónimo Rüedi at his studio, Mexico City. Photo: Iris Humm. Courtesy of the artist

Published on October 15 2020