Essay

A Modest Dressing Room: On Noé Martínez’s El sudor de las plantas

by Bruno Enciso

Inaugural exhibition at LLANO

Reading time

5 min

LLANO begins its operations with El sudor de las plantas (“The Sweat of Plants”), an individual exhibition by Noé Martínez. The artist investigates and produces images surrounding the processes of colonization in Mexico’s Huasteca region during the first years of the conquest. This is a complex project, bringing into consideration several different layers: the work’s material formation, its assemblage, documentary research, as well as the salvaging of personal and family memories. Each layer operates in its own time and stimulates different patterns of experience. They do not hinder or exclude one another—on the contrary, they join together and deepen the imagery that the artist wants to show us. In subtle—but by no means elusive—ways, the show puts the viewer on hold: waiting for a live act.

Noé has invoked ancient presences, and the gallery is arranged as a kind of modest dressing room. There, on the roof of a factory, the spirits who have answered the call will be able to rest, to look up at the sky, and to contemplate that valley about which the wind has told them so much. They are attentive to the arrival of visitors because each of them is a possible spectator. They are mortals and their faces are half-covered, just as they were told to do. Only with those who appear receptive will they be able to interact.

The pieces are everything they need. There are hides, canvases, pendants, and prints for wearing, pictures with useful notes for directing one’s movements, as well as a text, written by the artist himself, for avoiding improvisation. Each one of these elements has its particular powers, although the direction of the act largely depends on the will of these phantasmagoric presences. Some will want to perform a solemn and eloquent soliloquy. Others will be terribly confrontational with the spectator, maintaining a tone of reclamation. The most experimental will seek to join up with whoever will listen to them—in order to imagine new horizons. All of them know that there had been violence before; it’s the place where they start out.

In the text there is much to attend to. The very gesture of writing a serious accompaniment from the position of the producer seems to me quite remarkable. It could be a poem, a song, a crude script, or a series of independent vignettes. The writing in verse demonstrates a sincere scriptural exercise, one that elaborates on the works through experimentation with the lyric—instead of opting for the rigidity of documentary data or for a severe declaration of principles. I salvage one of its 26 stanzas:

Each that I see that I broke

each piece breaks again

Fragments of tongues

Fragments of cosmos

Reading this text inaugurates an intimacy that, on the one hand, offers a certain clarity towards the artist’s position regarding his own work. On the other hand, it enables a multiplicity of temporary routes for thinking about coloniality in that invented territory, America; sometimes it is one’s own history, other times that of others, that of living bodies or that of ancestors. The images coined by Noé flow gloomily, ambitious in their form and bitter in their taste. It always behooves one to take distance.

(The full version of the text can be requested at info@llano.mx)

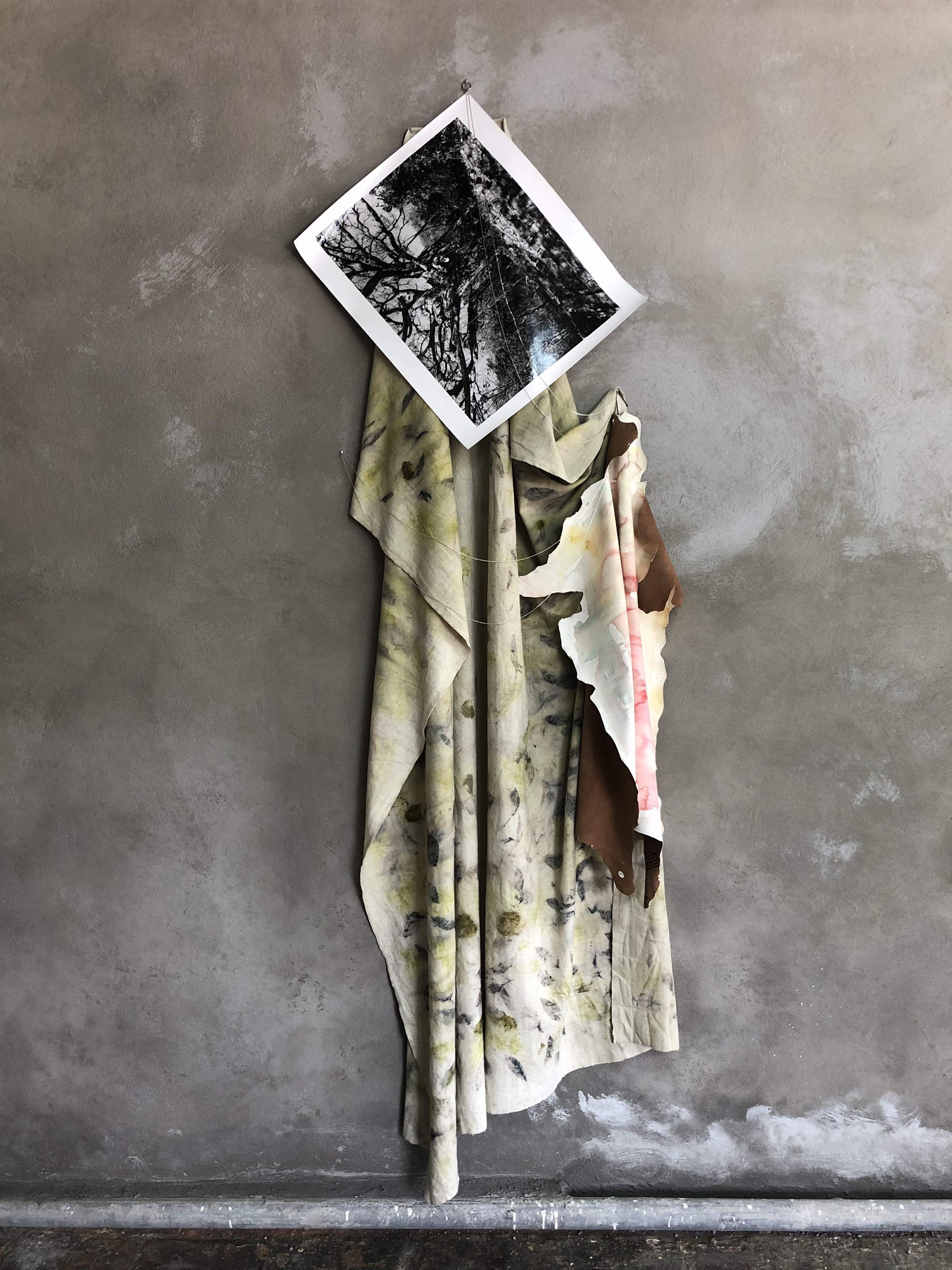

There are five pieces that can be worn. Each one hangs down from a single point, showing its folds and its lack of seams, revealing its materiality, its weight, and its state of rest. Four of them combine canvas and hide, printings with tobacco, muscle, and rue. In these are found water, heat, and plants that produce steam, aroma, and relief. They leave a discrete mark. Plants sweat in order to heal wounds. The fifth piece refers to those wounds, perforating the natural weave of the canvas with replicas of the insignia with which enslaved bodies were marked.

All five of them include photographic prints portraying those places that witnessed barbarism, as well as chains that accentuate the violence and material interest that traversed the dispossession of virgin lands. A sixth repeats the motif and is integrated into the logic of repose: it is a necklace made with pieces of porcelain, decorated with signs of the Huasteco imaginary and with gold. Together, these pieces that sooth, that hurt, that adorn, make up a group of dispersed elements awaiting a force that would encourage them and take advantage of their material values in order to cause commotion.

Finally, a series of pictures trace bodies in different positions, apparently naked. Silhouettes overlap, surrounded by hazy auras. Some annotations are repeated and repeated; they always point to the mouth expelling them. “To speak is to exist absolutely for the other” (“Hablar es existir absolutamente para el otro”), says one. Whether as a registration document, an illustration of a mantra, or as a script of movement, the series introduces the presence of a crude, indistinct body, one that modulates its forces and movements in order to get in tune with other bodies. Chaotic diagrams of flesh that sweats and knows itself to be vulnerable to time and other invisible forces.

I do not think that spectating an act like this can produce a profound introspection derived from shock at the reminder of a trauma. Still less with all the possible variants. What is feasible and fortunate is the use of materials and their complexities in order to seek a sensitive approach to the issues worked-out in these productions. In the best of cases, the viewer will be attentive to the manifestations of ancestral energies, which always carry with them valuable memories.

The exhibition will be open until December 19; schedule your appointment in advance here.

Translated to English by Byron Davies.

Published on December 3 2020