Interview

Time of the Sculptural: Interview with Benjamín Torres

by Mariel Vela

The artist opens the doors of his studio during Material art fair

Reading time

8 min

For its eighth edition, the Material fair changes venue. Calle Sabino 369 will open its doors to receive artists and galleries from different parts of the world. The new location distinguishes Santa María la Ribera, San Rafael, and Atlampa as neighborhoods that, owing to their innumerable studios and cultural organizations, have become essential to the art scene in Mexico City.

As part of the fair’s Invited program, Mariel Vela visited and interviewed two artists working in the area: Cosa Rapozo (Guanajuato, 1987) and Benjamín Torres (Mexico City, 1969); the latter presents new pieces at the Pequod Co. booth.

Opposite Benjamín Torres’s studio in San Rafael is the Cine Ópera. Two statues abide on the marquee of its dilapidated entrance; they are the muses of tragedy and comedy—Thalia and Melpomene. I haven’t been able to figure out from which material they are carved, but I take it all as a kind of prelude. Upon entering the building, there’s another marquee, this time made of felt:

201 DANZA ARAB_ [ARAB DANCE]

205

206

207

208 ESCUELA EN MESES [MONTHS-LONG SCHOOL]

209 DENTISTA AARON [DENTIST AARON]

306 ESCULTOR [SCULPTOR]

307 BUFFET DE ABOGADO [LAW OFFICE]

401

502 PINTORA LEONOR [PAINTER LEONOR]

(I think there are correspondences between the maestra of Arab dance, the dentist, and the sculptor. A concern regarding the shapes and materials of a body in space: enamel, dentin, cementum, bite alignment. The correct disarticulation between pelvis and ribs in order to achieve particular undulations in the belly, the temperature at which bronze melts.)

A sculpture is a presence telling us about the time it contains, and when I finally enter the studio I can observe all different times in Torres’s work. Their comings and goings, their loneliness and accompaniments: these collages happened to be next to the Japanese paper lamp, while the ceramic swan is found between spray cans and tacks.

Mariel Vela: I think there are media that call us, ways of understanding matter that make us gravitate towards certain explorations. How did your interest in the sculptural begin?

Benjamín Torres: It began when I entered the visual arts degree at FAD (UNAM’s Facultad de Artes y Diseño, or Faculty of Arts and Design), formerly ENAP (Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, or National School of Plastic Arts). At the faculty I took workshops on sculpture, clay, assemblage, as well as stone and wood carving. Suddenly I had access to a series of possibilities, the whole idea of three-dimensionality, of the object, began obsessing me; that’s when I became interested in sculpture. At the end of my degree, I took a final seminar with a Japanese sculptor: Uei Horibata Tadashi. It was my first trip to Japan, and he helped me to consolidate my ideas regarding relationships between space, matter, and time, as well as to understand matter as a container of ideas that’s located in space and that requires time in order to be experienced. Uei Horibata Tadashi is part of a sculptural movement and a Japanese sculpture school called Mono-ha, which is very influential for many artists and also for me; it starts off from the sculptural experience that produces the relationship between time-material-space.

MV: Even though painting also contains a time of its own, there’s something that particularly intrigues me about the time of sculpture, and that’s its relationship with another body, sometimes human. When there’s an element that affects a path through space, for me it becomes an experience that’s not only sculptural but also choreographic.

BT: One of the peculiarities of the sculptural is that it shares space with us, unlike painting, where a portal opens that for me is a border. You enter painting from the visual, but to perceive the idea of the sculptural you must travel through space, and that journey takes you to a certain time; as you go around the sculpture, you modify it and it modifies you.

At the back I see one of Torres’s most recent series, titled Colisiones temporales [Temporary Collisions]. There’s a search to disarticulate or to disarm a way of representing the human body in classical sculpture. I recall that in the new version of Suspiria, by Luca Guadagnino, one of the dancers suffers from a curse that makes her contort in impossible ways. I ask Benjamín if he’s see it, perhaps insisting too much on continuing to talk about dance. After all, in 2011 he worked on a series titled Bailarinas (Degas).

BT: This project (Colisiones temporales) has several ideas around it, and one of the main ones is collage. Before, I worked on collage for about six years and always with a basis in the idea of construction; constructing an image from fragments. I decided to work with very pre-established aesthetic categories, and I began looking for prefabricated sculptures that circulate in the popular imaginary, such as Greek, Roman, Egyptian sculpture, or certain schools of neocolonial sculpture. These images circulate on a massive level, since they not only belong to the art world, but are also established within popular culture. For me, these images occupy the same place as the images that I take from mass media in order to make my collages. They’re part of that same imaginary, but they circulate in another way. I began collecting these sculptures just as I collect magazines: I tear them up and with the fragments I reconfigure the idea of the representation of the body, but also its aesthetic categories. This produces corporealities in metamorphosis, which is also very much the idea of collage, that act of transgressing forms. It comes a lot from avant-garde experiences: breaking with a whole, with a totality. Bursting that totality, and then with those fragments forming another totality.

_and_concrete_43_x_20_x_20_cm___16_9_x_7_87_x_7_87_in.jpeg?alt=media&token=ef7bbf73-5a06-4b9e-8c12-d1712d720938)

MV: What’s your relationship with the neighborhoods of the city where you live and work?

BT: San Rafael and Santa María la Ribera are the neighborhoods where I spend the most time, and there’s an idea beyond these specific spaces in my work that has to do with the contexts where I’m living, working, and that directly affect my production. It’s an idea that comes from the avant-garde, to take the city as a laboratory of ideas, a workplace or a space that you can appropriate, intervene in, and affect in some way. This affecting is always reciprocal. The project Dislocaciones Demarcadas [Demarcated Dislocations] is situated there.

MV: In these graffiti where before there was text and now we only find the intuition of some letters, of meaning, there’s something at stake. What happens for you in that transit?

BT: It’s an exercise in translation and transformation, the passage from a textual language to a sculptural language. It doesn’t lose a certain relationship with its origin, which interests me a lot. My work has a very formal part, understanding the form as a container of concepts, but there’s also a nervous dimension. I like the idea of the nervous more than that of the emotional. Francis Bacon insisted a lot on this. He didn’t talk about emotions in art; he talked about the nervous system, and that idea is interesting because the brain is part of the nervous system. It’s a way of understanding the experience that touches the sensations, but also the ideas.

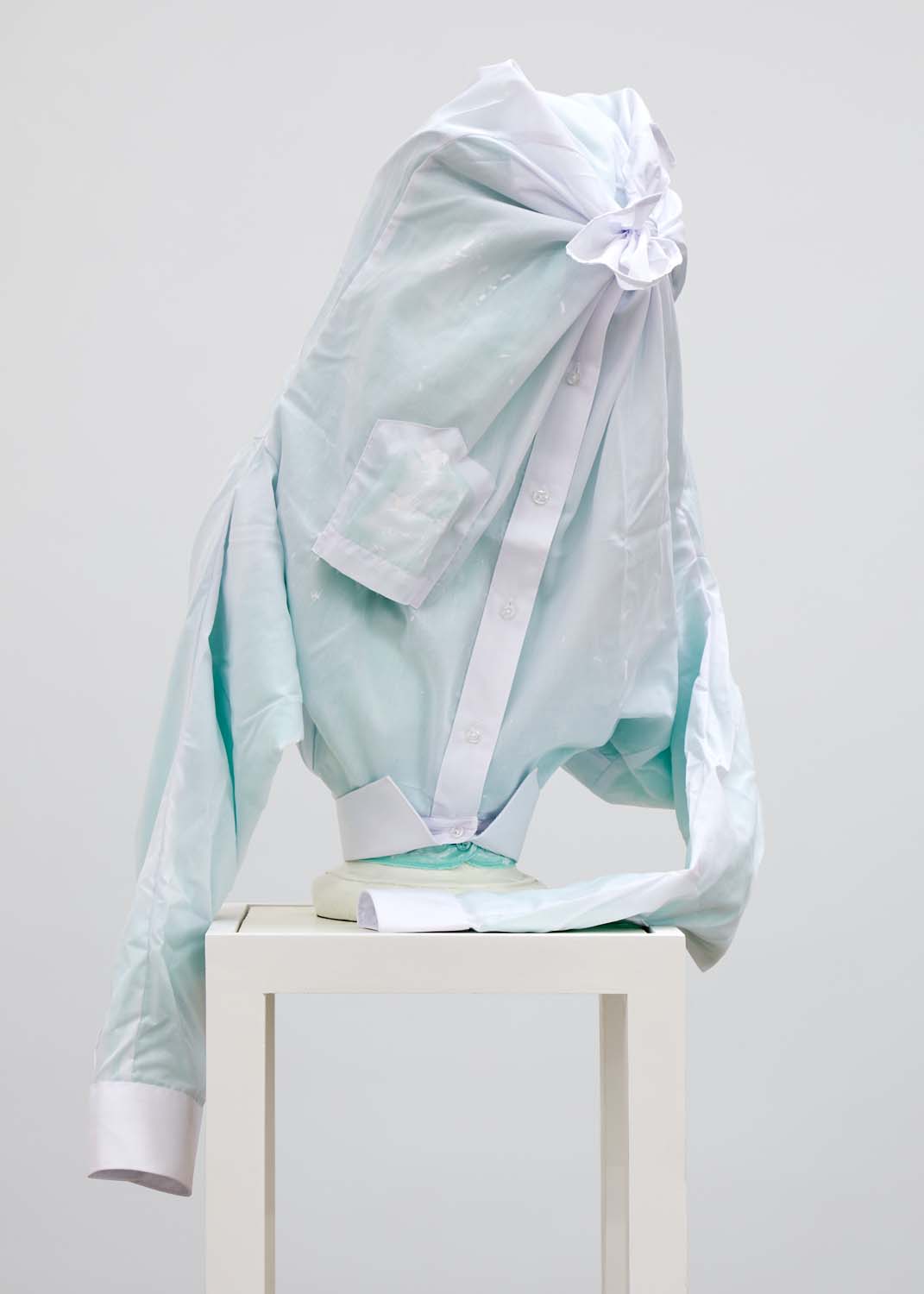

MV: That’s very interesting: to think about the hormonal and chemical dimension of the encounter with objects, even prior to the encounter with the idea or concept. For example, there’s a mysterious tenderness that these wrapped volumes cause in me. What’s under that smooth surface—what contact zones are created?

BT: This series of wrapped objects is based on the idea of blocking in order to reveal something. These covers in order to show something: it’s a practice that comes a lot from collage. By doing this you show an aspect that you hadn’t seen of that image or that object, even though it also comes together with the idea of furoshiki, a practice that interested me a lot on the last trip I made to Japan. It’s this daily practice of Japanese culture that consists of wrapping objects in order to transport them, protect them, or give them as gifts. I think there’s definitely an idea of care within this practice, although the concept of mystery is also implicit. Also something that interests me a lot is the question of how to work the surface of a sculpture: how can color intervene?

MV: Yes, something that I perceived regarding color is that there was a change of palette in this series, a gravitation towards other compositions.

BT: The pieces with very shrill colors—for example, the ones in Dislocaciones Demarcadas—come directly from the context of the city, all its artifice, the mass media, and the strident information flows. Nevertheless, on this occasion I worked on the idea of color from other references: the compositions of furoshikis and kimonos. There’s a kind of work with color in Japanese culture that interests me. If you look, there’s a transparency here that’s very subtle, a mint green shows through the white shirt. The light reveals something to us.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on April 30 2022