Interview

Rodrigo Hernández: Circular Conversation

by Carolina Magis Weinberg

In the basement of the Museo Jumex there’s an inundation of black circles: an image in which one can move between dimensions

Reading time

7 min

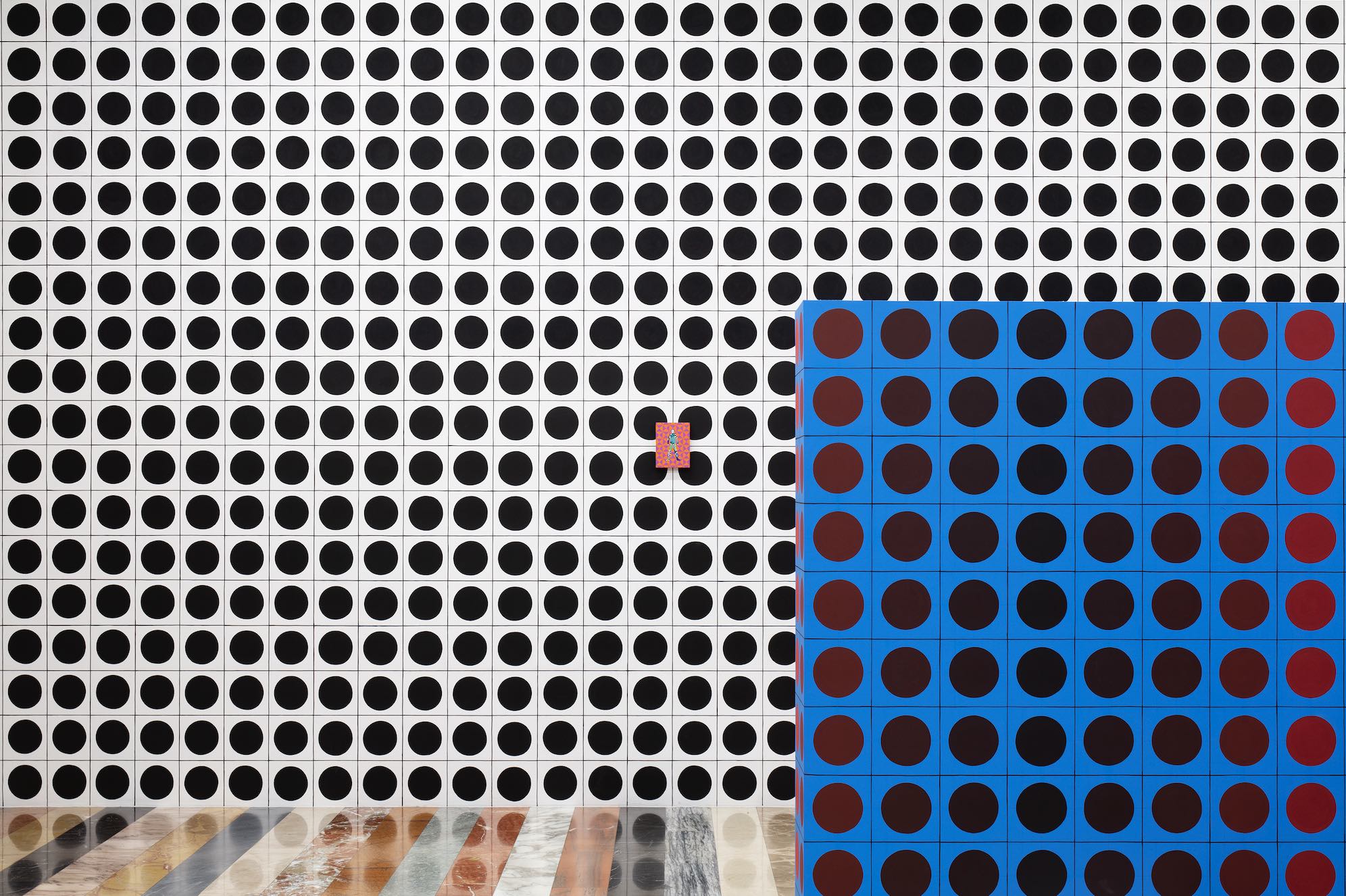

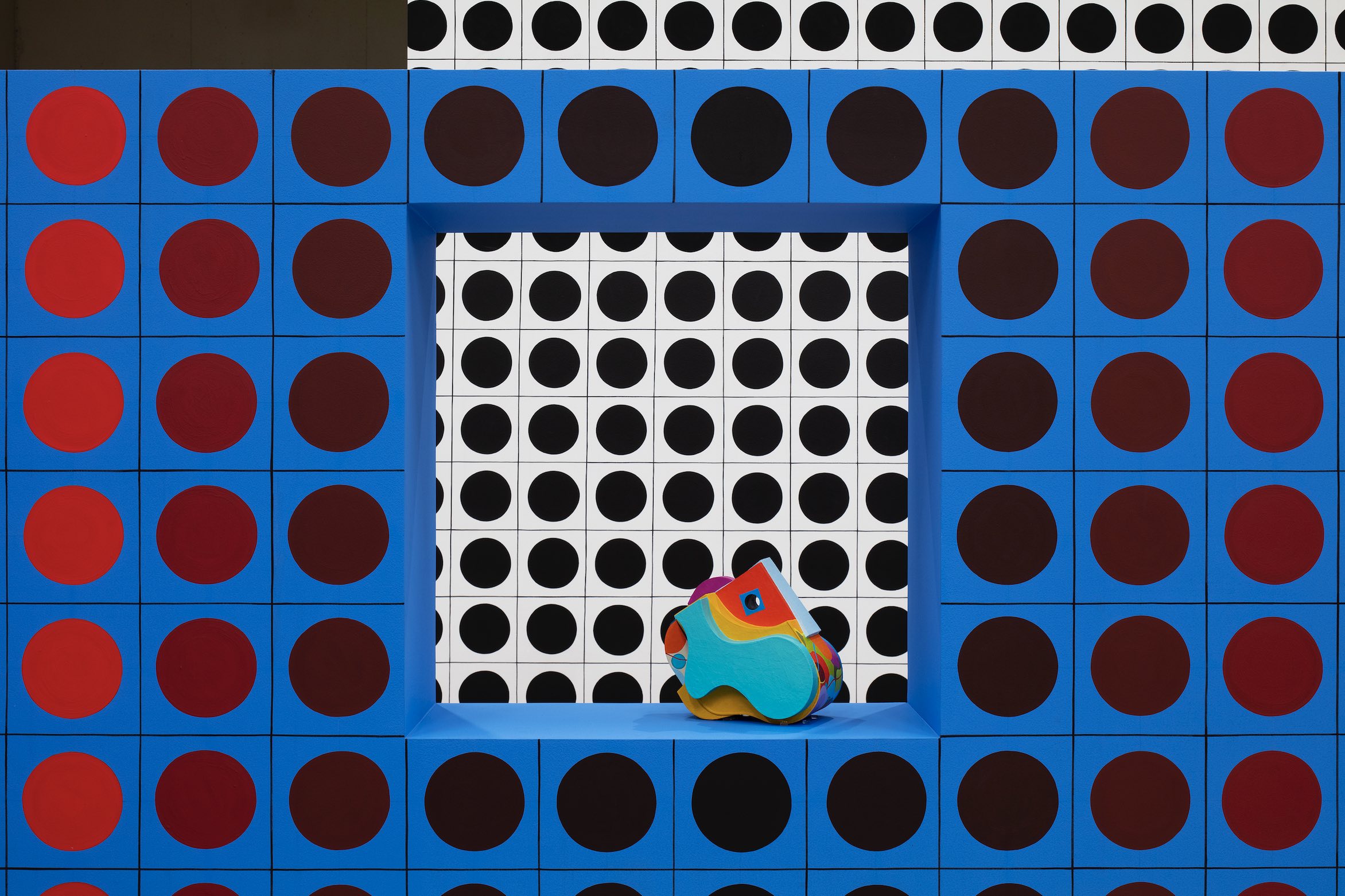

In the basement of the Museo Jumex there’s an inundation of black circles: an image in which one can move between dimensions, between figure and background, between positive and negative. The blurrer of distances responsible for this spatial event is Rodrigo Hernández, who is presenting El espejo [The Mirror]*. His installation is an exercise in vicinities: some physical—in space—and others virtual—in time. Whoever visits the image-space with curiosity will find between flatness and volume discreet red strips that open camouflaged drawers. Inside them one will discover fictitious letters between two characters from the history of image and design: Antonio Grass (Colombia) and Verner Panton (Denmark), both with parallel searches in different corners of the world. They had never met, until now; one is the circle and the other is the semi-sphere. The exhibition is a juxtaposition of dichotomies, a sum of duplicities that, being together simultaneously, add up and cancel each other out, becoming something else, a third liminal space. It is there, in the visual alchemy of supersaturation and the high contrast of patterns, that the possible encounter lies—a distance united by the superimposed forms; that’s where the mirror is.

Leaving that space drenched in circles, I was left with a few questions.

Dear Rodrigo:

I have a question for you. If you want, you can check with Antonio and Verner on the answer: Does a sphere reflected in a mirror become a circle?

Hi Caro,

That’s not an easy question to answer. It depends on whether the eyes of the sphere are perfectly aligned with the mirror surface, on what angle they’re seen from. Also, one variable to consider is where the light comes from, and whether or not this causes shadows to appear on the sphere that reveal its volume. But the moon’s a good example showing that it’s not so easy to know what you see when you look at an object.

Rodrigo

Dear Rodrigo:

An eye in a sphere. Two eyes in a sphere. Are the eyes circles or are they spheres? Would a sphere have only two eyes? If we squared the sphere and in each space we painted a circle? Is the moon a mirror?

Carolina

Hi Caro,

The moon has fascinated me for a long time. In 2009, sitting in a park, I asked my teacher Silvia the question, “What is the moon?” What we immediately agreed on was that there was no aim of finding answers with this question. Rather, it works as an invitation to a state of reverie, rather than reflection; or as an agreement of principles for a conversation free of all tethers and purpose, like the ones that children have. In this way, if someone said that the moon is a button, why would that be wrong?

I recently read that the moon, in the dark, reflects. And perhaps this is another way of saying that the moon is the mirror of our dreams.

Rodrigo

Dear Rodrigo:

Apart from questions in a park, what are some other ways of arriving at those states of reverie? Could one get there by seeing a million circles simultaneously?

Is reverie something close to dizziness, saturation? Do we dream with the eyes?

Carolina

Hi Caro,

I had just been reading about those various paths to a state of reverie (to put a name to it now). As it happens, I came across an idea by the psychologist Timothy Wilson which proposed that the traditional model of consciousness in the west, in which this was the fundamental signifier of human existence, did not fully fit contemporary reality. Instead, he says, consciousness is rather an ephemeral phenomenon that only comes into operation when it has to—that’s to say: when we’re surprised by exceptional circumstances that require its activation. Outside those moments, Wilson says, “we navigate the world like a dog in a semi-conscious, dreamlike state.” There’s a text that I come back to often by David Hickey that links this subversion of the definition of consciousness to Op-Art, fundamentally saying that an optical painting is a lesson regarding that threshold from which our ability to interpret the world begins to degrade and finally ends up completely disintegrating. Through a literal method, that is: based on nothing more than visuality, this type of art insists on the absolute otherness of a world that exists beyond the “self”. Vision and knowledge are two concepts that appear to be randomly associated, but we could ask ourselves to what extent this association is sustained and for what reasons it should be.

Rodrigo

Dear Rodrigo:

I recall that in your talk at the exhibition’s opening you spoke about how the molds employed for the three-dimensional elements were plastic spherical objects used as peepholes for dogs to peek out at the world, allowing visual contact with the outside from the inside. Based in what Wilson says, do you think that looking through that peephole would allow you to get out of that canine dream state, in order to see consciousness?

Carolina

Hi Caro,

I’ll share with you something I wrote the day after opening the exhibition in Medellín: “It’s possible to enter the inside space of a sculpture and see what it contains. In a formal, physical, and spatial sense, but also metaphorically, it’s possible to enter its conceptual composition. To enter the web of forms that formed it, of images that imagined it.” But, as you mention, it’s worth remembering the original function of those acrylic semi-spheres that I used to make these sculptures: they’re used to cover a hole that’s made in the lower part of a wall so that a dog can peek outside. The dog never manages to get out, but it does manage to have a partial and limited view of what’s going on outside, keeping it “present” on the street even if it’s still inside. It’s also important that it’s not a complete, closed sphere; it’s not a self-contained form. It’s rather a semi-sphere, and, in the case of the sculptures, its other invisible half is in the same territory as the viewer. In fact, there’s nothing left of the sphere but a skin on these objects, a space molded to receive it, a kind of impression or reflection of an invisible body. The line that separates/joins these two halves is invisible, and vision is something that comes and goes through that line. In the inner world of a sculpture, many forces, aims, and ideas come together, and I feel that the human ones are only a part of them, only one of the channels of a great flow of forces traveling in all directions. If a sculpture is that crux, its nucleus is that divided sphere that receives and is traversed by vision.

Rodrigo

Dear Rodrigo:

So I remain there, on the border between semi-sphere and world. Finally, I leave you with the question that has intrigued me ever since I immersed myself in your patterns: is a letter a mirror?

Carolina

Hi Caro,

Yes, it can be. When you read something that someone else has written—for example, a person you love—you are trying to see their face looking at you while you read; you imagine their words spoken to you and their listening to those words while doing so. There’s a whole illusion that creates a letter in order to try to shorten the distance of its meaning. One's reflected in that letter, but what you see is the other.

Rodrigo

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*: El espejo by Rodrigo Hernández is on view at Museo Jumex through October 30, 2022. Curated by: Marielsa Castro Vizcarra / Letters written by: Rodrigo Ortiz Monasterio

Published on August 28 2022