Review

On stealth in 'No se hace el silencio' by Israel Martínez at Espacio Morelos

by Maya Renée Escárcega

Reading time

9 min

The Japanese toilet, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki suspects, is the space where haiku poets have conceived many of their ideas. It's an environment with a degree of darkness, absolute cleanliness, and silence so complete that the buzzing of a mosquito can be heard. In this context, the silent liquids, the temperature, and the surfaces, which both in shadow and in penumbra receive light, generate a moment of mystery.

The silence in Mexico of our times is different. Right now, its deep sonority / that seeps into the rocks¹ / is that of the tanker truck rather than the shrill of the cicadas. It is also not the silence of John Cage's body inside the anechoic chamber. That is the impossibility of silence itself, which, if it exists, no ear will be able to hear.

Israel Martínez presents in Espacio Morelos video, soundscape, installation, and intervention in a public space that tends to silence. This theme has tied his practice together over the years. The exhibition allowed him to meditate on his methodology, based on long-term and medium-scale processes. He revisits pieces created for specific projects in specific spaces and brings them together with explorations produced without a defined exit. It is a process that can be understood as slowing down to create art again or making sound explorations to generate aural experiences.

Pausing is significant in a trajectory like Martínez's. He is an artist who has dedicated himself to exploring sound to generate social and political reflections through critical thinking. Issues surrounding the violence of a narco-state and a world that lives the consequences of the free market economy have guided his artistic investigations. These investigations delve into revolution, counterculture, social protest, activism, and other forms of resistance and persistence.

He resorts to music industry strategies such as remixing or sampling. These are also understood as exercises of appropriation or recontextualization; of hypotext and hypertext, to reformulate and configure previously exhibited pieces and create alternate versions of themselves. Hanging on the facade, a 4-meter-long canvas frames the phrase: “El silencio era más impresionante que la multitud” [The silence was more impressive than the crowd]. Prior to materializing on a portable device, the statement was hand-painted on the facade of a store in Oaxaca in 2018, where it remained for two years. The quote comes from Los días y los años, a novel in which Luis González de Alba, an LGBTIQA+ activist originally from Guadalajara, recounts his testimony about the 1968 student movement in Mexico, specifically, the Silence March on September 13. This march was held a few days before the start of the Olympic Games.

The Olympiad was the scene of another act of silent protest. Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists wearing a black glove, a black power salute, during the 200-meter awards ceremony. The sound of silence was the sound of footsteps and the holding of air. It was a reminder that it is presence and not absence.

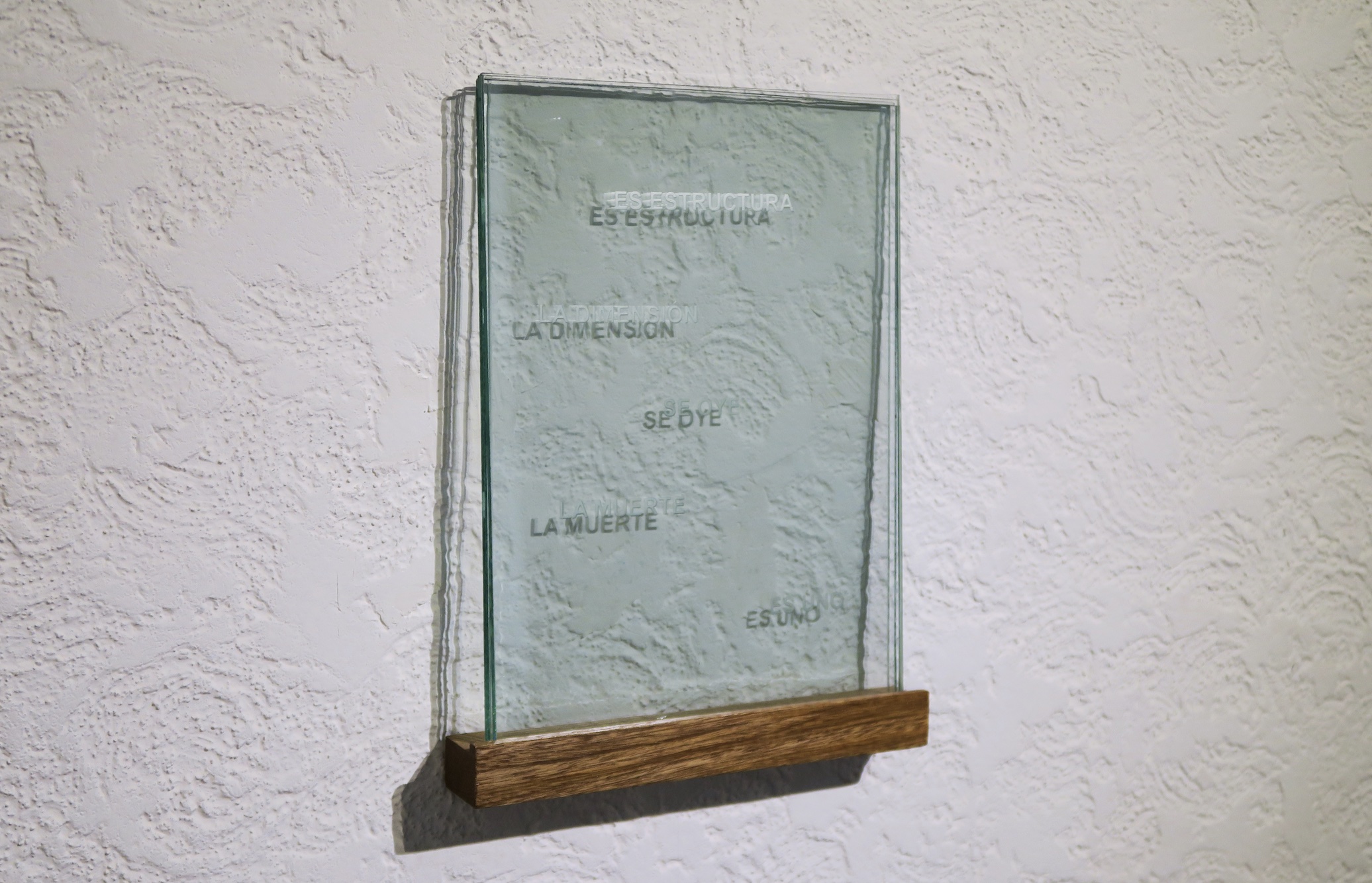

For more than a decade, Martínez has been exhaustively underlining the allusions to sound in all the books he reads, generating an archive from literature. Written on the wall of the staircase, the poem reads: Ahora nos vamos / a contemplar el eco / hasta agotarnos [Now we are leaving / to contemplate the echo / until we are exhausted]. Inspired by Japanese calligraphy and Zen aesthetics, Contemplar el eco (2024) [To Contemplate the Echo] was created specifically for the exhibition, based on a haiku by Bashō remixed to allude to sound. Similarly, five glass panes engraved with phrases by architect John Hejduk allow the viewer to rearrange the work. The remixing in Se oye (Hejduk) (2024) happens in the hands, eyes, and inner voice.

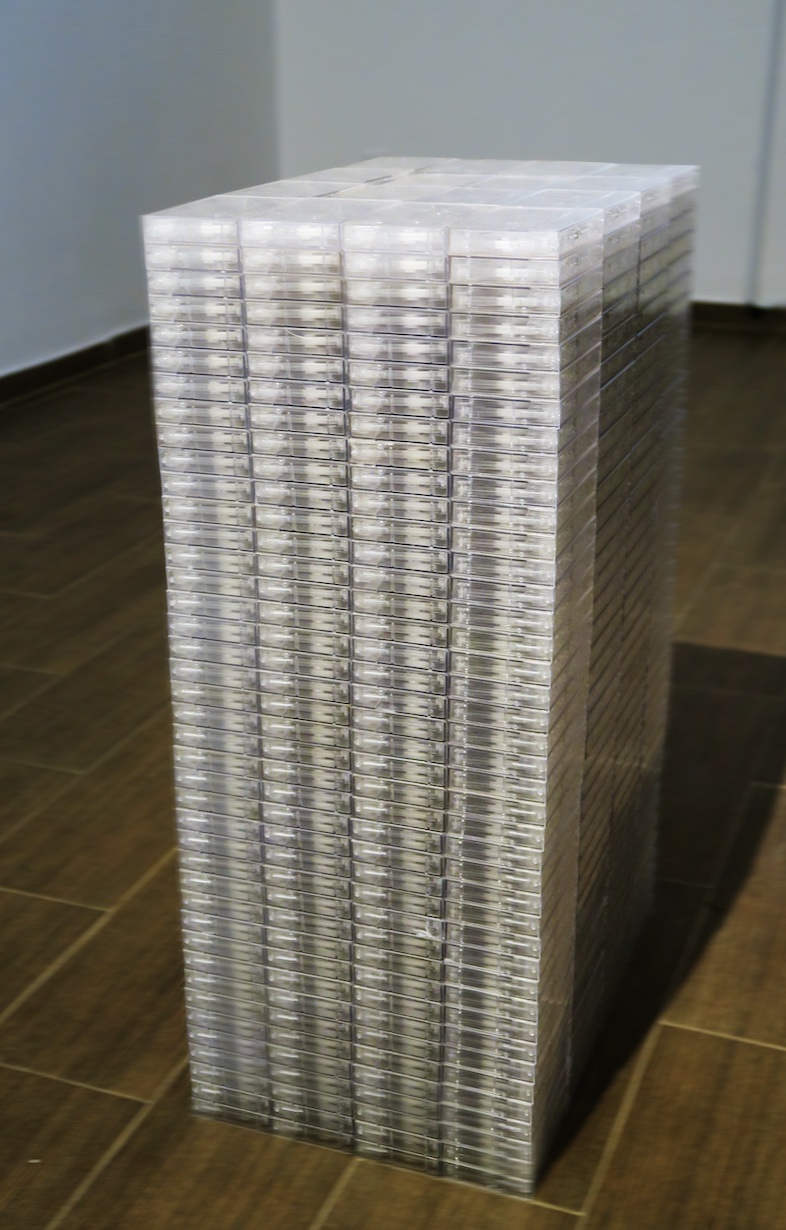

Imagen Pública (2017) [Public Image], an installation of 666 cassettes recorded from punk, alternative, and vernacular music albums, is concerned with the dematerialization of sound. Taking content from Spotify and YouTube, the artist meditates on the virtual loss of the media that store music, as well as its attached objects. By means of a typewritten index on pink and yellow paper, he gestures to the inserts that distinguished one cassette from another in Imagen Pública², a store that operated selling copies in the 80s and 90s in Guadalajara. This motif also draws from the source of the DIY ethic associated with punk ideology and anti-consumerism. At that time, buying imported products in stores like La Manzana Verde and El 5º Poder meant better print quality, inner linings with photographs, and a booklet with song lyrics.

Martínez reconfigures the form, remixing the layout of the cassettes in correspondence with the exhibition projects. In Arredondo \ Arozarena, 2017, it was a micro-district of housing complexes. In Casa del Lago, 2018, it was the Chihuahua Building, a witness to the state crime perpetrated in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco in 1968. In Centro Interpretativo Guachimontones "Phil Weigand", 2023, it was the "I" shaped ball game field of the Teuchitlán tradition. In this exhibition, it is a block. The sculpture takes a step towards itself, focusing its attention, first of all, on its (in)material components: the recorded songs, the long listening, the reading, the extended writing, and the prolonged silence in the object (one of the weapons of silence is time: ). Secondly, on the physical support that stores the music in the present and ties it to the world of objects: the server.

At the back of the room, Resultado de un silencio cruzado II (2019-2024) [Result of a Cross-silence II] reproduces the silence of impossibility. It is the result of what the imagination does when it is deprived of seeing, hearing, smelling, accessing, or feeling what is well known to be present, real, and close. In Martínez's case, it was the stubborn sea of Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands, Spain, a port city in the Atlantic Ocean. In the installation of sound and visual landscape, projected on a screen, Martínez summons us to contemplate the same and the only sea he saw from his room: a painting by an unknown author that reminds us of the Homeric sea, with its purplish horizon between the sky and the sandy sea. Equally alternative is the sound of the sea, where the (absence of) waves sound like the murmur of traffic, wind, and birds, mixed with voices, footsteps, engines, bells, and tires accelerating and braking.

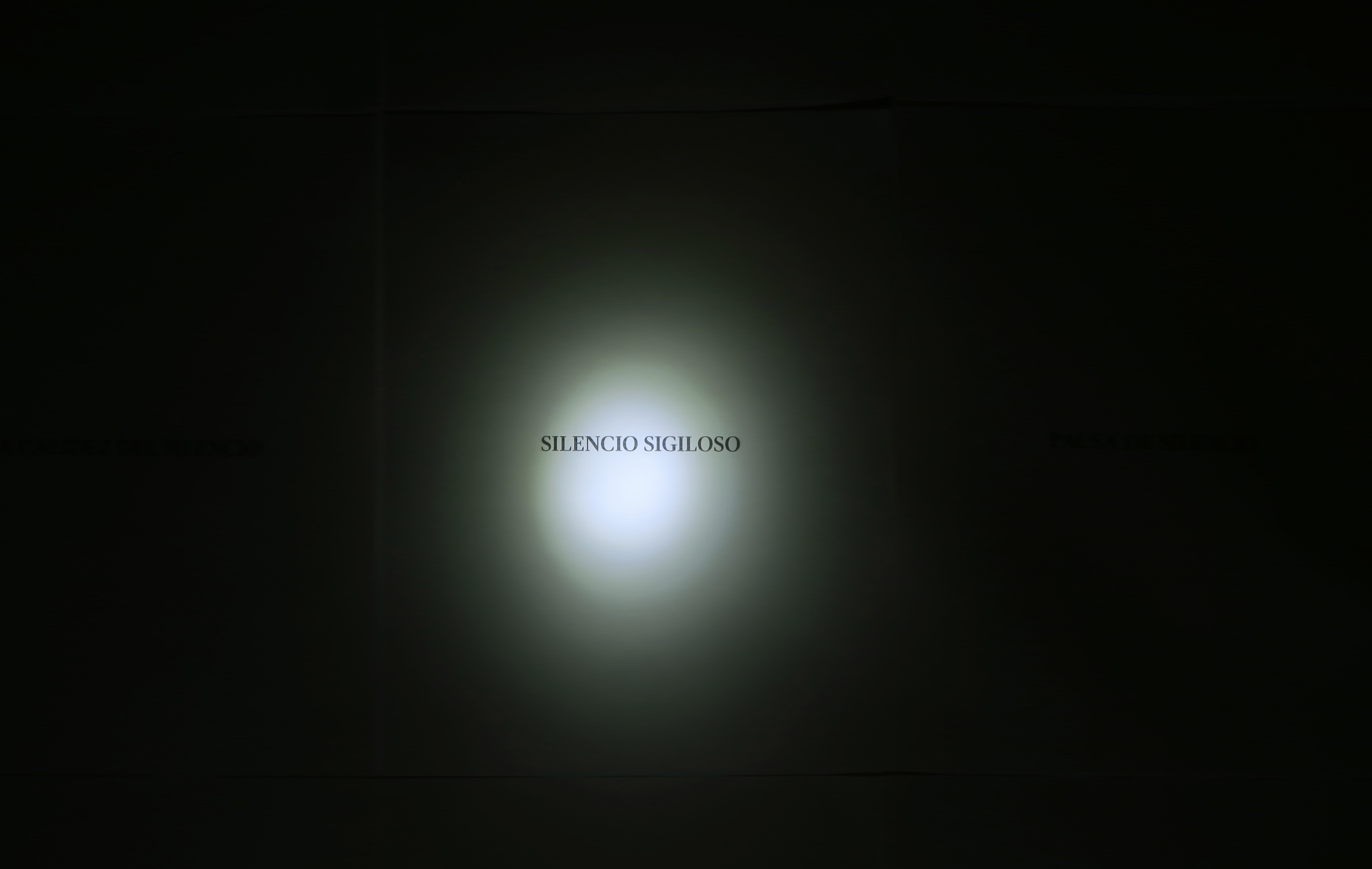

The tour ends in a darkened room accompanied by a soundtrack. Inside, an extensive whiteness of paper is transformed into a background, a landscape of emptiness. With the support of a flashlight, the whiteness of each sheet of paper reveals a sentence printed around silence. In 666 aproximaciones al silencio (2024) [666 Approximations to Silence], each notion was taken from a text in literature, history, or philosophy. In the background, Encapsular la quietud (2024) [Encapsulating Stillness] is testimony to its sonic expressiveness. The piece conveys field recordings in silent places suitable for reading such as the living room, the park, the subway, and libraries.

Its silence is that of Blanchot, the silence inherent to reading and writing. Each printed sentence reminds us that the act of writing is a way of breaking it, but like the room covered with allusions to it, also of inhabiting it. For it is not only a matter of filling the void, but of dialoguing with it. And at the same time that of Barthes, that of the authors who keep silent to let the text, the silence, speak for itself.

The explorations on sound by Martínez often start from stealth, a silence that, by definition, is marked by the caution of knowing that it is the depository of a confidence. The Spanish word, by etymology, is linked to written language. It is the object related to the guard and custody of information; the stamp as utensil, sign, and impression in a classified document.

In the past, other artists have used silence as a response to the trivialization of language, communication, and silence itself. In harmony, Israel Martínez presents it as an affirmation: "Silence is not made," which Esteban King presents in the exhibition's hall text as a question: "Is silence not made? (Is silence not made?)". It is possible to think that if the silence that is not made is the absolute one, that which is only theoretical, the silence that is made is produced by creating environments that favor perception (such as the traditional Japanese toilet). Silence is an active listening experience (Nancy). Cage used the verb "To make" to refer to his writing process, as active as that of listening to musical composition.

"Making" is more inclusive, isn't it? For instance, it would include breathing with writing, hmm? It could include other things than just writing. It could include breathing… it could even include listening, so one would "make" a text partly by writing, partly by breathing, and partly by listening, don't you think? "Making" seems to include more variety of possibilities, of kinds of action.³

Thus, stealth, at least in the pieces in this exhibition, expresses its sonority from textuality (and not precisely from literature). In the reception of the works, it is perceived in the sound of subvocalization: one's own voice reading, remixing, and reflecting on the objects that express mutism. The melodies that make a sound from memory when reading the typewritings of Imagen Pública; the internal meditation on an action from the ethics of care (stealth) or the morality of justice when remaining silent at times when the situation requires raising the voice. These are just some of the internal noises that operate.

Susan Sontag resolves that in the arts, silence can only exist as a permanent silence, either because the artist renounces his vocation or because the work ceases to exist. Never in the literal sense as the experience of an audience, nor as the property of a work, there is no neutral work of art. My only question now is whether or not neutral silence is made.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

1: deep silence

the shrill of cicadas

seeps into rocks

—Matsuo Bashō

(1644–94)

2: The store took its name from Public Image Ltd, a post-punk band formed by former Sex Pistols vocalist Johnny Rotten.

3: John Cage in conversation with Joan Retallack in "Musicage: Cage Muses on Words, Art, and Music", University Press of New England, Hanover, NH, 1996

Published on June 5 2024