Interview

Making the Unicorn Appear: Interview with Zahara Gómez Lucini about Recetario para la memoria

by Sebastián Machado

Reading time

8 min

In Mexico, in the last decades, 77,171 *1 persons have been recorded as disappeared. For Ignacio Irazuzta, disappeared persons constitute a sociological figure, one that concentrates and at the same time crystallizes properties of the social; that both produces identities and represents them; that resignifies events; as well as one that twists and turns the social and individual life of those who are touched by the disappeared person’s absence/presence. This figure articulates past, present, and future. This figure is also a total social fact, encompassing and linking together various dimensions of social existence: economic, juridical, religious, psychological.*2

Forced disappearance is an action exercised, involuntarily, on a person removed from the space of law. It is not known if they are alive or dead; it is not known, it has not been known, nor will it be known until they appear. For the artist Zahara Gómez Lucini—from an Argentine family, born in Madrid, raised in Paris, settled in Mexico—the word disappeared has within her own history an almost mythological origin, so that by dint of repetition “it’s no longer understood very well what it is, and it becomes a unicorn, something almost magical, fantastical.”

Emanating from a problematic inherent to language and its ways of defining us, we find that the systematic repetition of the word disappeared gradually empties it of meaning. From there it becomes something imaginary, different for everyone, something that thereby dematerializes. Nevertheless, disappearance*3 in sociopolitical terms is a methodology based on terror, an instrument of communication towards others.

There is a common denominator in the projects that Zahara has carried out: traces. Throughout her career, crossing different territories and temporalities, she has investigated different ways of claiming justice—from the tools of forensic teams in Chile, Argentina, Mexico, or Colombia, to memory archives found in folders of infinite research in Guatemala. Although Zahara began by treating these last trenches against oblivion from an academic point of view, it is interesting to note that her process has consisted in the migration of these themes toward photography, turning this medium into another instrument for telling stories.

Since 2014, a group of women known as “Las Rastreadoras del Fuerte”*4 (“The Trackers of the Fort”) have gone out in search of their disappeared persons in various parts of Sinaloa every Wednesday and Sunday. Zahara got to know them between 2016 and 2017. In the interview she said:

On that first trip, the aim was, beyond the work, to document. On that trip I stayed at the home of Mirna Nereyda [one of the leaders of Las Rastreadoras] and we shared a bed the first day we met. So there was a fucking intense level of intimacy, since we slept in the same bed and she showed me photos on her phone. I remember our both lying down and Mirna telling me: “Look, these are photos of Roberto…” So it was a matter of all of a sudden entering into a super intimate space, without any barrier. Later, on the second trip, I happened to coincide with some journalists who were there to take notes and it really shocked me: the interviews were conducted in the offices of Las Rastreadoras, and suddenly I realized that, perhaps because the questions are always the same, I don’t know, the story was always told in the same way.

After that experience, Zahara asked herself where that kind of script of pain emanated from, one that naturally repeated itself with the telling of these stories: “Who consumes these stories? What are these images made for? What questions are they [Las Rastreadoras] being asked so that the answers are always the same?” It’s here that the photographer felt the need for a break in ways of telling these stories, thus moving away from the repetition of an official and statistical discourse.

Collaborative

What is a collaborative project? Communal work as something that shares an authorship—necessarily linked to being with and for others—is a matter that Zahara has long engaged with.

I’d like to do a project with all of you [Las Rastreadoras], but I don’t know what that format is and I don’t know what it means to be collective. But I don’t want some photos of you as victims, some photos of you with the washed-out portrait of your son. To me, as an audience, that’s something that no longer reaches me; it makes me sad, but it doesn’t produce in me anything else.

It’s in the coexistence within the shared spaces of tracking—in the offices, for example, in the houses, in the moments that are not ones of searching—that one can perceive that other perspective, that other story, the other layers of life.

Recetario para memoria (“Recipe Book for Memory”) is a collaborative project between Las Rastreadoras del Fuerte and Zahara Gómez Lucini. Part of two axes: the social and the gastronomic. It collects the favorite recipes of the disappeared and seeks to put on the table an encounter with absence and memory. In that sense, it has several objectives: on the one hand, to feed memory while traversing from the intimate to the public; on the other hand, to learn to cook and to socialize using those recipes, based on the resistance of Las Rastreadoras, who consider it the case that “they are alive as long as we have them in our minds.”

Zahara starts out from the space of the kitchen and of food, which is conducive to several things. It allows for the possibility of bonding in a common space with people who do not have a missing relative; and it allows for the result of what takes place there to bestow identity onto those who were taken. In addition, and this is important, it makes possible a rewriting that puts aside the vision of the mothers of the disappeared as victims.

They’re not just suffering women, it’s a much more complex thing. They’re bad bitches who come out of the desert, with a shovel, looking for needles in a haystack. That’s the stuff of super heroines. From there other perspectives emerge; you become aware of stigmatization and you look for ways of breaking with that message.

A key moment of the project takes place when there appears that individual ritual from which the collective emerges: not only that of cooking a dish, but also that of cooking it for the one who is absent. This gives rise to an exercise that straddles the documentary and the photographic: cooking that food, eating that food, and making it public.

The photo doesn’t matter in the end; the whole process of cooking, of sharing that space, of waiting for the dish to be ready, of talking with some people about the missing person and with others about something unrelated, all that space is charged with a… I don’t know… of a making present of the one who isn’t there. Afterwards, the process of eating that dish is, as it is, feeding on memory, just like that, without metaphors. “I’m eating this, which in reality isn’t for me.”

The collaborative project invokes, through such everyday and common acts as cooking and eating, the exceptional. It’s a matter of presenting an event of transformation that, through the body, goes from the sensitive to what’s revealed as possible: being, even for a moment, with someone who is not and will not be until you find him.

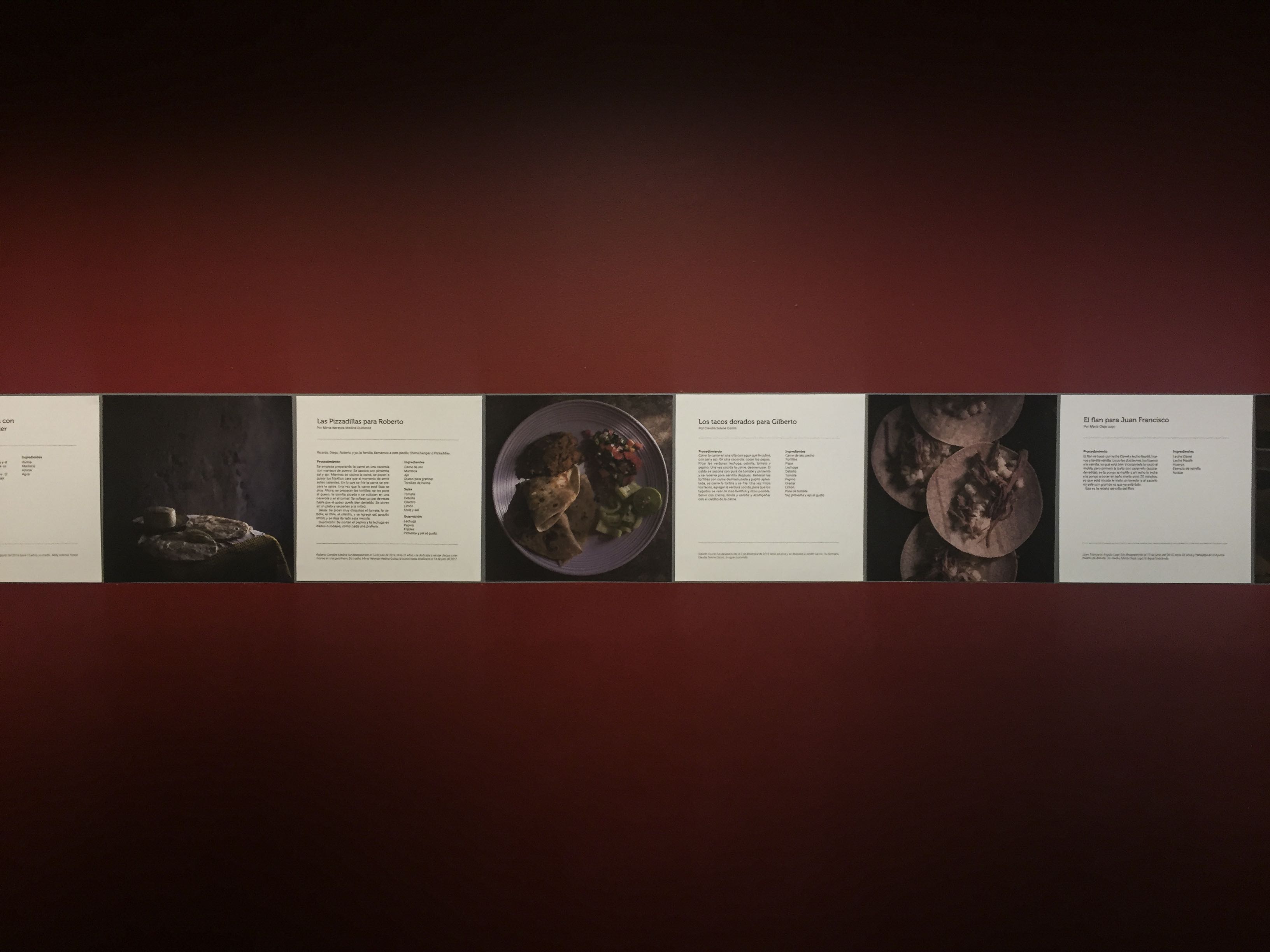

The forms of output are various and distinct. Among the highlights are an exhibition and a self-edited book—1000 copies made in Mexico City, at Imprenta Panorama—in which are gathered the steps for making each dish, as well as photographs of the ingredients and dishes, and photographs of Las Rastreadoras cooking and searching. This approach aims to recover from their intimate spaces the day-to-day life of Las Rastreadoras. The book can be purchased in physical or digital format through the project’s website. This page also allows us to listen to the women in their own voice, to learn about their treasures, and to join, from our trenches, in collaborating in the project of collecting 61,000 missing recipes.

The physical exhibition is being presented at the Centro de la Imagen. Owing to the pandemic, we suggest visiting their website to confirm schedules and dates. It is important to prepare for the visit in advance on account of the current sanitary conditions.

Sebastián Machado is a Photographer and Student of Art History and Studies, Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana.

*1 In the latest report on the search for and identification of missing persons, presented in October of this year by the Mexican government, it was recognized that in Mexico there have been 77,171 persons reported missing and not located from 2006 to September 30, 2020. Source: Registro Nacional de Personas Desaparecidas y No localizadas (RNPDNO). Available at: https://www.gob.mx/cnb/documentos/informe-sobre-busqueda-e-identificacion-de-personas-desaparecidas-en-el-pais

*2 Irazuzta, Ignacio (2015) “La figura de la desaparición forzada: de la transnacionalización a su manifestación en México,” work prepared for presentation at the VIII Congreso Latinoamericano de Ciencia Política, organized by the Asociación Latinoamericana de Ciencia Política (ALACIP). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima, July 22-24, 2015. Available at: http://files.pucp.edu.pe/sistema-ponencias/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Ponencia-ALACIP-Irazuzta.pdf

*3 Gómez Lucini, Zahara, in an interview for this article conducted on November 15, 2020.

*3 About Las Rastreadoras del Fuerte: https://www.facebook.com/Las-Rastreadoras-del-Fuerte-267629457048946/

Published on November 26 2020