Review

Materials Carry the Weight of Their Own Memories: Sabrina Herbosa Reyes at Aparador

by Mariel Vela

Reading time

3 min

Encountering a sculpture is a choreographical act: two bodies of variable materials and dimensions enter into an instantaneous—even if almost imperceptible—relationship. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that history has seen collaborations between choreographers and sculptors. I think of the stage designs that Isamu Noguchi created for works by Martha Graham, and of the coreogegos performed by dancer Sonia Sanoja in complicity with Gego.

For her first individual exhibition, titled Elogio de mudanza (In Praise of Moving), Sabrina Herbosa Reyes presents some of her most recent sculptures. The word mudanza (“moving”) has the meaning of “action and effect of relocating” and at the same time comes from the Latin mutare, meaning “to change.” Without avoiding bias, the first thing I noticed when I saw Herbosa’s Instagram is that in addition to being a sculptor, she is also a dancer. What are the mutations that interest her?

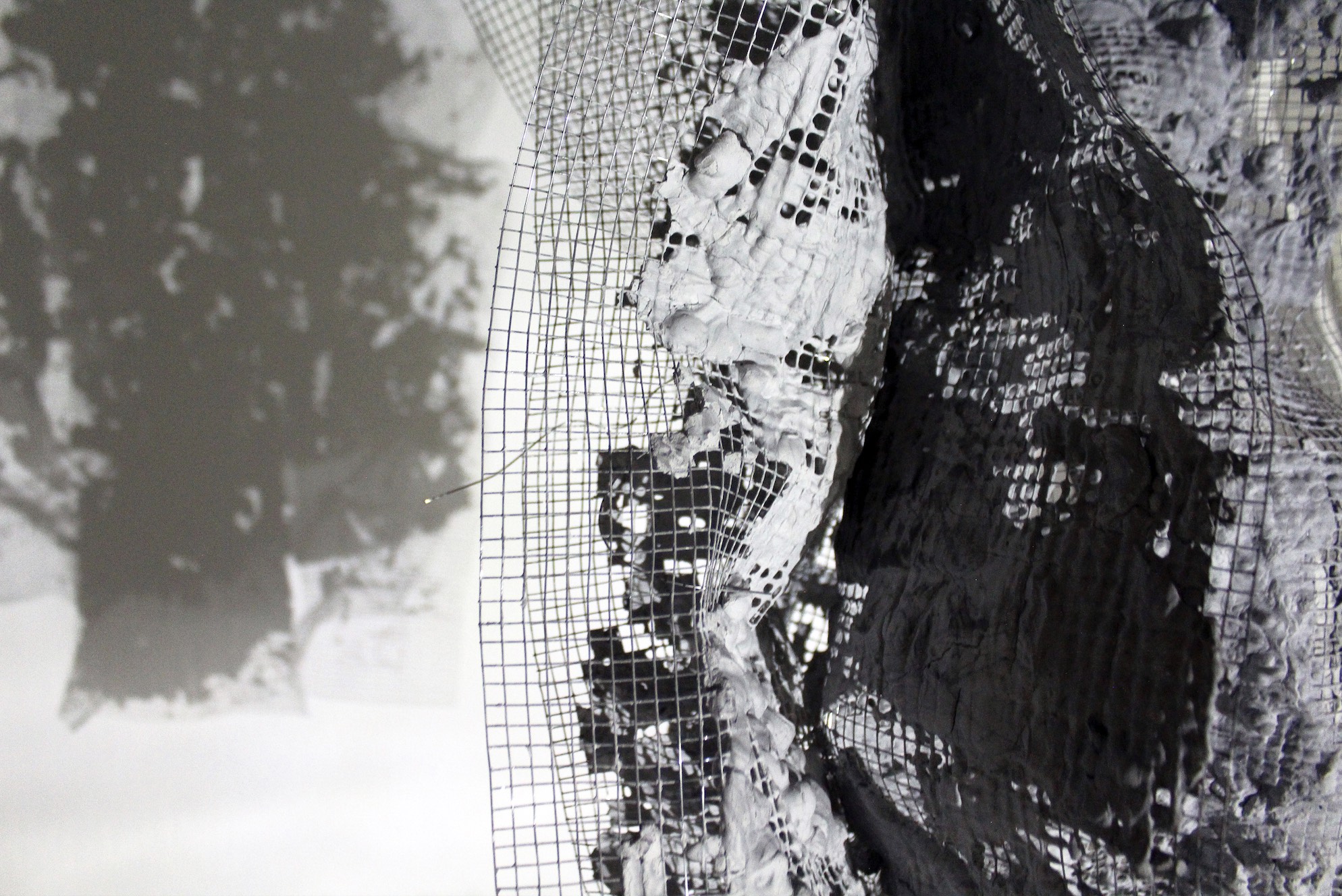

There’s something theatrical about the lighting inside Aparador. The space is nearly dark except for small spotlights that subtly illuminate some of the pieces. The sculptures titled Figures of Intuition rise up like trees or monolithic shoots of cement and metal; together they constitute an apparently organic assemblage. The piece The Last Bloom has its two upper extremities suspended, while the rest of the blackness overflows heavily upon the ground. A play of forces accentuated by the textile embalmed in concrete.

At the beginning of the 20th century, marble and bronze were replaced by industrial materials such as concrete, metal, and glass in order to produce sculptures: a rejection of the decorative excesses of bourgeois art. For both Herbosa and the curator, Gabriela Mosqueda, these industrial materials reflect an experience of urban daily life in the artist’s dérives, carried out in such cities as New York and Mexico City.

Upon arriving at Aparador, an initiative of Aldo Chaparro Studios, the first thing I saw was the large reddish gate, possibly of corten steel, patented by the United States Steel Corporation in 1933. The same kind that Richard Serra uses for many of his pieces. With which traditions is Aparador in dialogue via this gesture? What narrative parallels does it seek to generate? The materials carry the weight of their own memories.

The structures Wring Me to Dry I and II are installed side-by-side—a diptych of curved steel smeared with gray concrete. Both pieces hang from chains that look like necklaces and are illuminated against the light, producing sinuous shadows of grids invaded by stains. The ghostly presence of these drawings reminds me of some of Gego’s pieces, produced in dialogue with kinetic artists from Caracas such as Alejandro Otero and Jesús Rafael Soto. Despite being hung from above, they are suspended with a kind of near-immobility. Nevertheless, there is something in the materials that produces a vibration in the retina. An optical effect or perhaps a primary intuition that certain structures can awaken: spirals, golden ratios, golden rectangles, and electromagnetic fields.

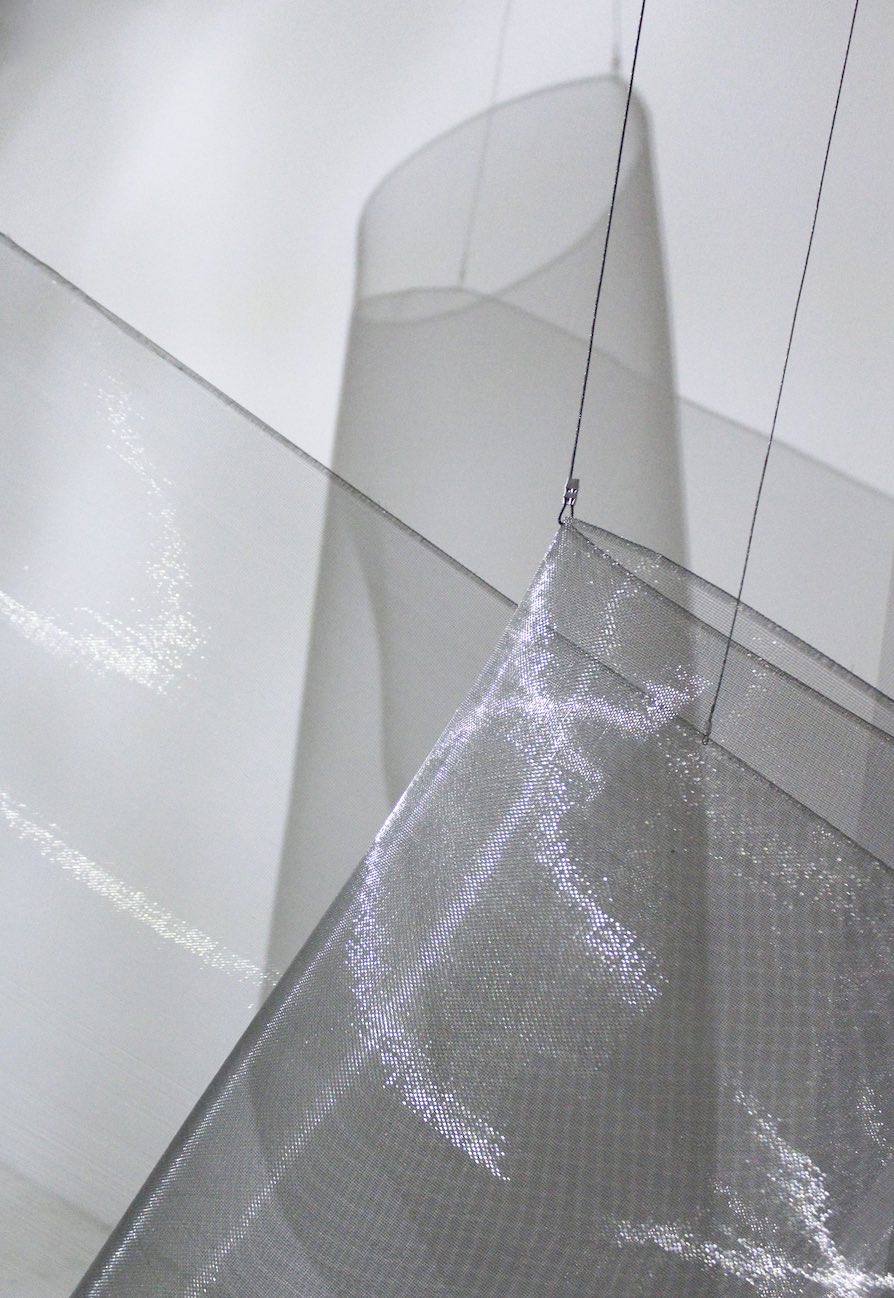

The installation in the background, titled I Follow You Into the Depths, reminds one of the Philippine Sea, from which the artist originates. Light—again an important element—produces tiny sparkles in this material created for industrial purposes, now turned into waves of metallic mesh. I watch Herbosa’s shadows walk within the oceanic piece and I imagine that they could be part of the scenery accompanying a dance. Perhaps the dance is in the structures themselves.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on June 22 2023