Interview

A Sea-Filled Mansion: Interview with Allan Villavicencio about the Murals Transcapes

by Fabiola Talavera

At Academia 14

Reading time

5 min

I was running late; the traffic wasn’t moving. It had been a very bad idea to try to arrive by car, on a Saturday, to Mexico City’s Centro Histórico. The same traffic light was going from red to green continuously. I got out of the car. In a hurry, I walked down the middle of the street among all the weekend market stalls. Soon I arrived at my destination, number 14 on Calle Academia, with its 17th-century colonial facade.

At the entrance I saw a knick-knack store; I wasn’t sure if I had arrived at the right place; I approached the gentleman overseeing it, and told him: “I’m with Allan.” The gentleman raised a plastic curtain and indicated where to go. Inside, I found a grayish courtyard and a huge central stairway leading to a large room. There, the artist Allan Villavicencio, beginning a few weeks ago, has been painting fresco murals as part of Transcapes, organized by Karen Huber Gallery.

.jpg?alt=media&token=b5c4aed5-d85d-469f-9d0c-858d1c278feb)

Regarding the technique, Allan gives me the details of the long process involved: first he does a sketch thinking that it will be carried out on a large scale; he traces out a sinopia on the wall, defining where the elements will be; he also mixes burnt lime and water, and applies the white mortar in sections; he then marks incisions on the lines with a tracing paper, and, before it dries, in a span of about eight hours, paints the walls with a mixture of water and pigment.

Until now Allan has worked mostly on canvases with oil or acrylic, leading me to ask him about how the fresco’s technique has affected his most recent production:

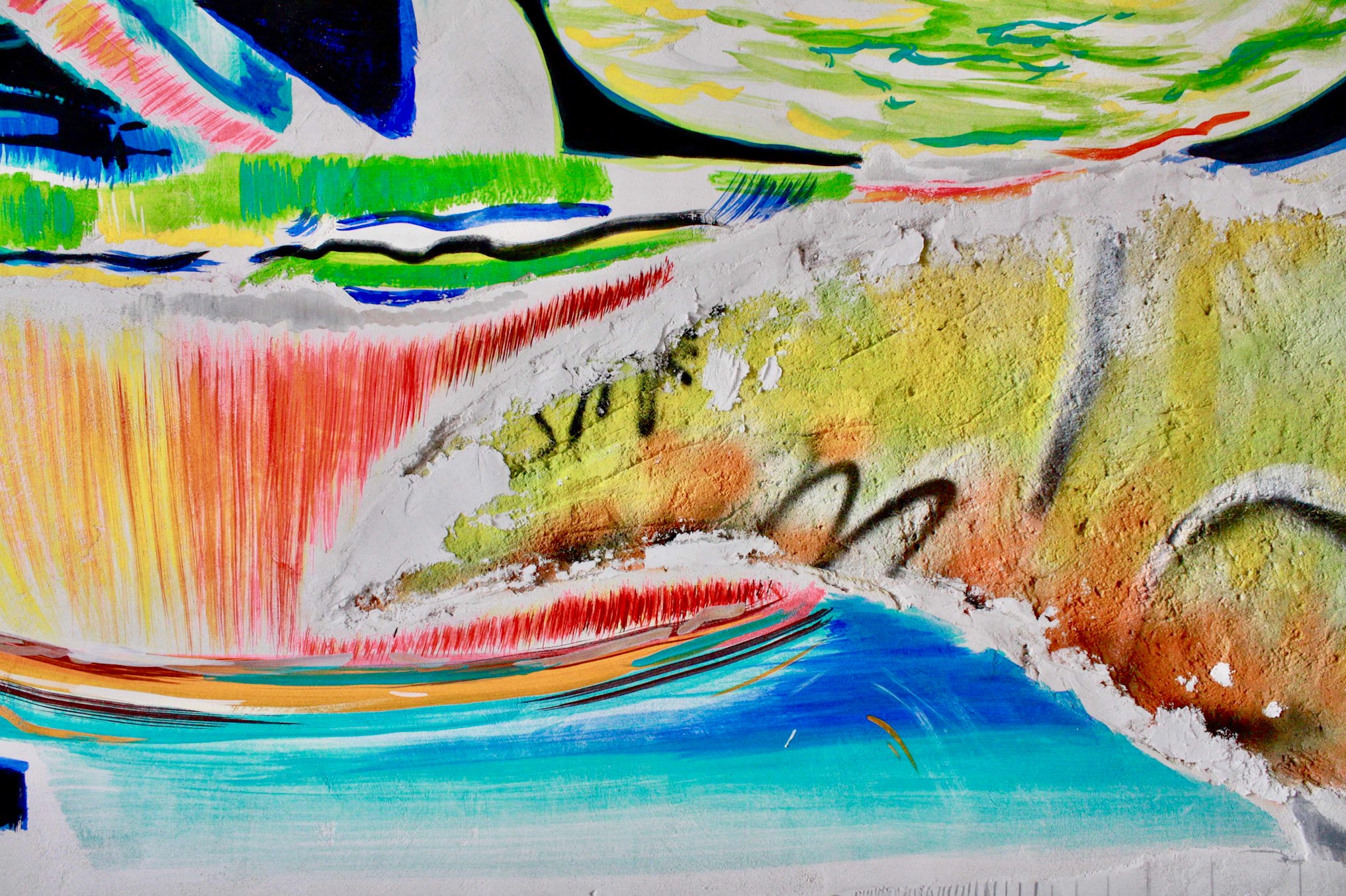

I think a lot about an image’s configuration on the basis of its borders. The fresco has allowed me to generate assemblies in parts, in an ad hoc manner together with the collage. I started doing fragmented things, not covering all areas of the fresco, but as if on a canvas: like when you leave the raw canvas so that the fabric is visible. I’m going to play around like that a little, leaving traces in order to highlight the process that runs from beginning to end.

Unlike with a canvas, the fresco requires much more planning. If something goes wrong, the mortar must be completely removed and the process begun again. Little by little, it accumulates marks or crusts that make evident the path of trial-and-error.

It’s not the first time that Allan has worked with elements close to collage. The artist remarks that urban fragments have helped him to configure his work’s visual vocabulary:

I’ve worked a lot with the idea of the visual obstacle: in ads, on walls used to paste ads that are then torn off. There I began to find formal elements in order to be able to reconfigure a broken, torn, pierced world…At some point these visual elements of the street were visual components; now they’ve become methodological tools.

Another important reference for the artist was an exhibition of Huichol pieces, where he learned how the Huichol use colors in order to enhance their symbolic application. Color is very important in his work; he has managed to consolidate a palette that distinguishes him as an artist, with phosphorescent colors that create a presence without being strident.

Besides that, the forms that appear in the mural do not seek to generate a specific narrative, but rather seek to evoke an animistic sense derived from dynamism and symbology. Nevertheless, these elements are in constant transformation, and respond to the same process of painting. The same thing can be a hole at one time and a leaf at another.

In the mural we can distinguish representations of sea and sky in a composition that obeys its own logic and its own gravity. We can also see stars and sea animals bearing toxic colors. The maritime elements are not alien to Allan’s work; in this fresco, nevertheless, they are enhanced by the aqueous medium that the fresco demands and by the colors it uses. The artist says that a difficulty for the fresco is the limited range of pigments available. He had to research different lime-resistant colors and found some screeching turquoises, yellows, and oranges, many of them bought from abroad.

.jpg?alt=media&token=3b583213-41b7-4343-9974-4a6b668e46b5)

In addition to his interest in composition and color, Villavicencio is interested in the material’s long-term life. When mixed with water, certain pigments are more resistant to lime than others; some of them will disappear, while others will dampen. “Due to the great weight of the technique, it seemed important to talk about the disappearance of the image itself or of some of its parts. I wanted to highlight this transitory issue of pigment, color, disappearance, and retouching,” he emphasizes. Thinking about the mural’s conservation, Allan proposes a set of instructions to be followed if it becomes necessary to retouch it.

Finally, when thinking about murals it is impossible not to make reference to the history of Mexican painting. This contextual framework led Allan to study the use of colors in muralism. This consideration is accented by the space where the mural is located: a few steps from the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, the birthplace of Mexican muralism. Nevertheless, what Allan creates in this old building seeks to stand out from the tradition, that which he reflects in the work and his way of doing it could not correspond better to the present-day context of Mexico City, to which he belongs.

.jpg?alt=media&token=102a76bd-5245-455c-9e0f-b0feb3e774ad)

Leaving this building, the chaotic market energy again strikes me again. The pathways are flooded by sunlight filtered through the vibrant colors of the tents. The musicians never cease playing their melancholic ballads. A route that Allan takes every day on his way to work on these murals.

To visit or get more info: info@karen-huber.com

Published on February 7 2020