_(1).jpeg?alt=media&token=3d74c8eb-0024-4b71-9967-6939559dbb57)

Review

Your Luxury Refuge, Your Colonial Experience. Mallorca and Acapulco at the CENART

by M.S. Yániz

Reading time

5 min

The more beautiful the scene, the more complete the horror

—Mohamed Mbougar Sarr

There is an equivalence between luxury and crime. Aesthetic modernism owes its existence to materials extracted from colonies across the Global South for centuries. The accumulation of precious minerals, spices, fibers, and skins resulted in forms that, to Western human eyes, are beautiful, as they reveal labor, technique, and exclusivity. "Whoever has money hides a crime," as Ricardo Piglia points out. Hotel chains not only remind us of this but serve as exemplary markers of the path from colonial violence to globalization. The hotel chain Camino Real owes its name to the routes traced through the territories conquered by the Spanish Crown.

It might have been surprising to attend the inauguration of a five-star hotel in Mallorca and Acapulco inside the National Center for the Arts (CNA), located in southern Mexico City. But since both the CNA and the Camino Real hotel were the work of architect Ricardo Legorreta, I experienced it naturally. Eight weeks ago, I received the invitation to the opening: a render of an armchair, generic modernist walls, the song El soltero by Acapulco Tropical, and the questions:

Isn’t globalization just a renewed version of colonialism? And what does Cindy la Regia have to do with Fray Junípero Serra?

Since my dad used to hand me the Cindy la Regia comic strip in Milenio newspaper as a child, I’ve been intrigued by how her figure unfolds a set of clichés associated with wealth and whiteness. Later, these became clear to me as issues around gentrification and coloniality—urgently pressing matters today in Mexico City. The invitation specified a dress code of retro Acapulco or American beachwear, but that day it was pouring rain. We stood there in long coats, drinking micheladas in the rain, staging the contradictions of colonial dreams in a modernist building that could well be in Acapulco.

At the back of the room, there was a timelapse of the decomposition and recomposition of the Acapulco coast—or Mallorca, or Cancún, or any other paradise destination—an intense smell of coconut and tanning lotion, a Camino Real hotel armchair, a series of gestures accompanying the hotel lobby experience, and the stench of micheladas from people coming in and out. I felt a deep nostalgia for a time I never lived in but to which we are condemned.

.jpeg?alt=media&token=11ada617-573a-462b-95f1-0ecaabac47da)

Your next destination is colonial, reads the title of the show, curated by Begoña Martínez with a wall text by Jaca Pineda. Before entering, there’s a panoramic photo of a beach with a lineup of luxury hotels. While it’s true that every human is destined to become someone, to capitalize on their skills, and to access the privileges afforded by their class, reducing the future to colonial repetition is terrifying. And yet: Your next destination is colonial, both prophecy and curse.

.jpg?alt=media&token=e0678396-234d-4235-a152-6c4774f25971)

The show—minimalist and profound—begins in 1749 with Fray Junípero Serra, the evangelizer of Mallorca in Mexico, who, besides bringing religion, also imposed territorial and economic control in the region. Years later, his figure was resurrected by dictator Francisco Franco as a cultural hero; monuments were erected in his name. Beyond Serra, Mallorca’s presence in Mexico is also evident in large hotel chains such as Grupo Barceló, Riu Hotels & Resorts, and Meliá Hotels International. Using these connections, the show presents works by artists from both Mallorca and Mexico who reflect on tourism and its colonial genealogies.

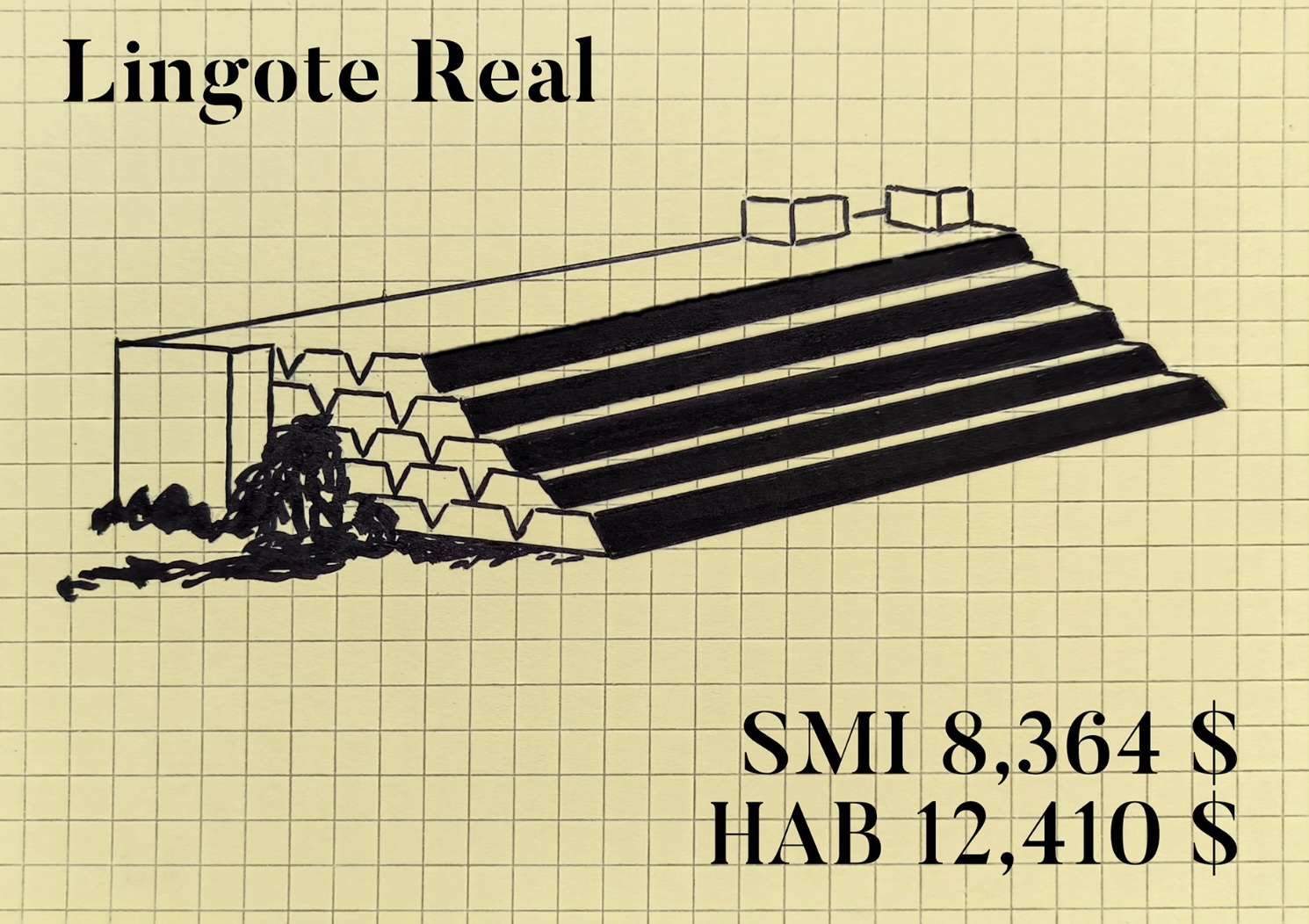

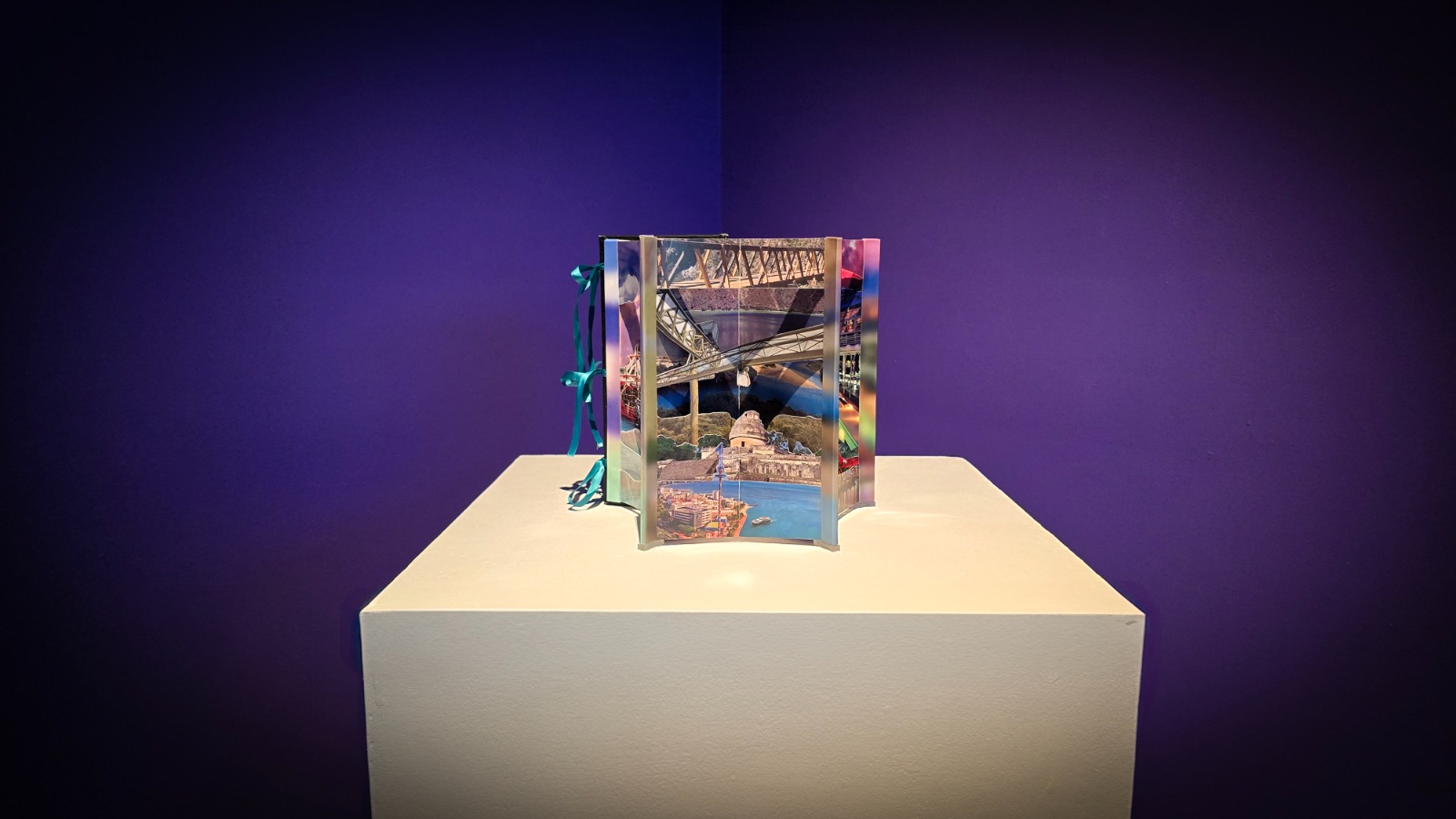

Biel Llinàs (Mallorca, 1994) presents perhaps the show’s cruelest piece: a 1:10 scale diagram of a Hotel Hyatt Ziva room, with a gold ingot in the back showing the monthly minimum wage in Mexico (8,364 MXN) and the cost of one night’s stay at the hotel (12,410 MXN). Sergio Monje (Palma, 1994) imagines every possible coastline using a timelapse of postcards from Mallorca, Acapulco, and Cancún, where hotel mass shapes the land and the passage of time. The video asks where true conquest occurs—virtual or real—since we rarely doubt what we see, even if it may not exist; colonization lies in the ability of multinationals to reshape reality at will without question. Marijo Ribas (Palma, 1982) shows a sepia diptych of Mallorca’s neo-medieval architecture that could easily be Las Vegas. Antonio Ponce (Mexico City, 1994) offers a (precariously produced) video on the tensions between neoliberalism and the history of Acapulco. Lastly, Xanath Ramo (Cancún, Quintana Roo, 1987) creates impossible, paradisiacal landscapes through collage, which could be found in any tourist brochure worldwide. The theme is luxury and the ghost of colonization. Despite the show’s beautiful landscapes, the entire space feels somber.

I sit on the hotel armchair and remember waking up in Acapulco last year. The morning was cold, barely dawn, and from my window, I could see the remains of yachts. Minutes passed, and civilians on rafts floated around, searching for anything valuable that might have been left behind. It’s been barely six months since Hurricane Otis struck Acapulco, Guerrero. All that opulence is now microplastics in the ocean. In time, the tourism industry will grow again, because disasters, in the end, are effective land clearers and poverty displacers. Then, art will be made from the rubble.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

Tu próximo destino es colonial will be on view at the Arte Binario Gallery of the National Center for the Arts (CENART) through August 3, 2025, from Wednesday to Sunday, between 10:00 AM and 5:30 PM. Admission is free.

Published on July 21 2025